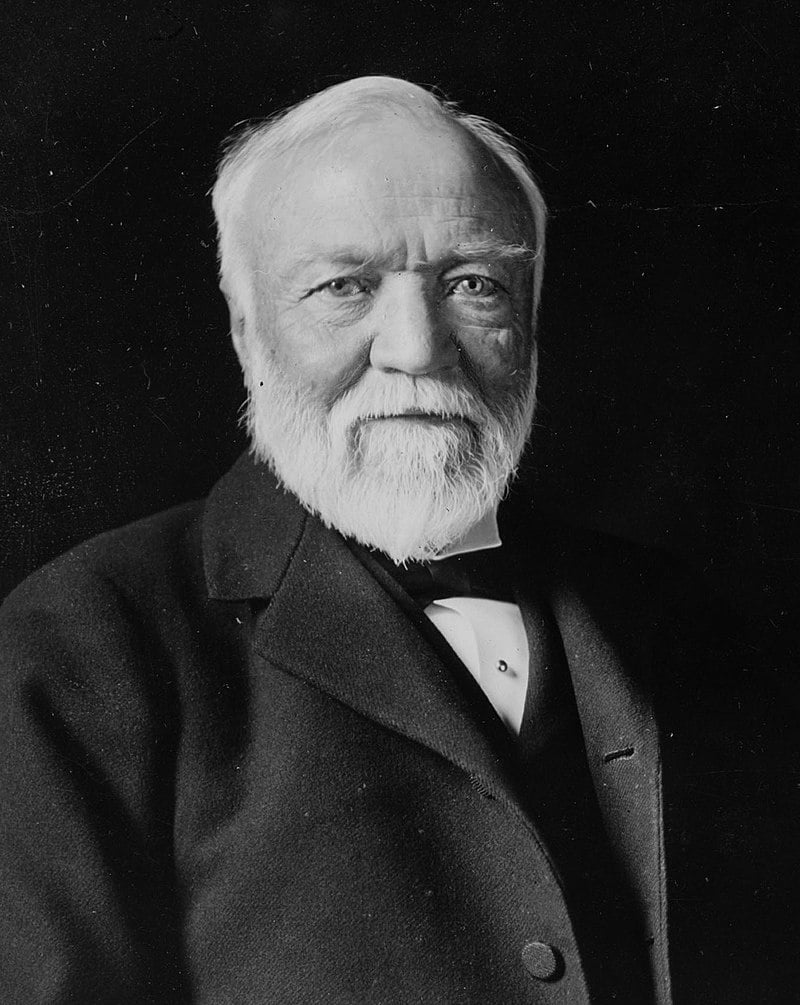

Andrew Carnegie (1835-1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and founder of the steel industry in the United States. He sold all his steel interests in 1901 to J.P. Morgan (who merged them into U.S. Steel). Carnegie became, for some years, the richest man in the world.

He gave away his fortune to a series of philanthropies in America, Scotland, and the British Empire, promoting libraries, higher education, science, and world peace.

Rejecting the "robber baron" epithet hurled by radicals, he opposed imperialism and was one of the most visible leaders of the Efficiency Movement in the Gilded Age and, during the Progressive Era, was a major proponent of philanthropy through the "Gospel of Wealth."

Early Life

Carnegie was born in Dunfermline, Scotland, on Nov. 25, 1835. His name is properly pronounced Car-nay-gie rather than the more common Car-nay-gie. His father, William Carnegie (? - 1855), a Swedenborgian in religion, was a hand-loom weaver who moved from the small settlement of Patiemuir to Dunfermline as that industry became more centralized.

There, the father became a relatively prosperous weaver with four looms and a number of apprentices, but he did not abandon the radical idealism of his forebears. They had been active in the Meal Riots of the late 18th century when workers protested the high price of grain supported by the Corn Laws. His radical proclivities were strengthened by his marriage to Margaret Morrison, daughter of Tom Morrison, a leader of Scottish Chartism, a movement to gain political reform for the benefit of the working classes.

The Morrison family were outspoken opponents of privilege in all forms: the monarchy, the House of Lords, the Church of Scotland, private education, and the protective tariff on agricultural products.

Andrew grew up in this unorthodox political environment that formed his earliest political and social ideals. In Dunfermline, the ancient capital of Scotland, he received his first love for history and romantic patriotism, which he never lost. During these years of rapid industrialization of the textile trade throughout Britain, the hand-loom weavers of Scotland suffered greatly, their income dropping steadily.

By 1848, William Carnegie had to admit to his family that there was no demand for his woven linens at any price. Selling their last remaining loom and borrowing twenty pounds from a neighbor, William and Margaret Carnegie, with Andrew and his younger brother Thomas (1843–1886), sailed for New York in May 1848.

Arrival in America

The family settled in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Pittsburgh, and at the age of thirteen, young Andrew found his first job in a cotton factory as a bobbin boy at $1.20 a week. William Carnegie failed to make a successful adjustment to this new environment so remote from his beloved Scotland and his looms, but his son flourished and soon became the chief earner.

Andrew wrote enthusiastic letters back to his friends in Dunfermline that here in America, he had found the practical realization of all the Scottish Chartist's dreams.

He became convinced for life that American republicanism was the perfect solution to Europe's long-standing political failures.

At age 14, the boy left the cotton mill, which he disliked intensely, to become a messenger for a local telegraph company. He met important people and took advantage of any business opportunity that presented itself. From this moment on, his rise in the business life of Pittsburgh was meteoric. He quickly mastered the art of telegraphy.

Thomas Scott, then superintendent of the Pittsburgh division of the Pennsylvania Railroad, in 1853 hired Carnegie as private secretary and personal telegrapher at $35 a month.

When Scott became general superintendent of the railroad, "Andy" at age 24 and only 5 feet 3 inches tall, took over Scott's major position in Pittsburgh and grew a beard to disguise his youth.

Civil War

In 1861, at the beginning of the Civil War, he went with Scott, then Assistant Secretary of War, to Washington to organize the military telegraph department. They set up railroad and telegraph connections essential to the defense of Washington D. C. Carnegie was appointed Superintendent of the Military Railways and the Union Government's telegraph lines in the East.

Carnegie helped open the rail lines into Washington that the rebels had cut; he rode the locomotive that pulled the first brigade of Union troops to reach Washington. Shortly after this, following the defeat of Union forces at the First Battle of Bull Run, he personally supervised the transportation of the defeated forces.

Carnegie was "the first casualty of the war" when he gained a scar on his cheek from working with telegraph wire. He would tell the story of that scar for years to come. Under his organization, the telegraph service rendered efficient service to the Union cause and significantly assisted in the eventual victory.

The defeat of the Confederacy required vast supplies of munitions, as well as railroads (and telegraph lines) to deliver the goods. The demand for iron products, such as armor for gunboats, cannon, and shells, as well as a hundred other industrial products, made Pittsburgh a center of war industry, with its railroads and telegraphs also essential.

Carnegie remained with the Pennsylvania Railroad for twelve years (1853-1865), but long before this, his interests had expanded far beyond the railway office from which he drew his modest salary. In 1864, Carnegie invested $40,000 in Storey Farm on Oil Creek in Venango County, Pennsylvania. In one year, the farm yielded over $1,000,000 in cash dividends and petroleum from oil wells on the property sold profitably. Carnegie was subsequently associated with others in establishing an iron rolling mill.

Carnegie had some investments in the iron industry before the war, and after the war, he left the railroads to devote all his energies to the ironworks trade. He formed the Keystone Bridge Works and the Union Ironworks in Pittsburgh. The Keystone Bridge Company made iron train bridges; as company superintendent, Carnegie had noticed the weakness of the traditional wooden structures.

These were replaced in large numbers with iron bridges made in his works. Andrew Carnegie bought into the Woodruff Sleeping Car Co. and introduced the first successful sleeping car on American railroads. In 1865, he became a partner in a small iron forging company in Pittsburgh, the Kloman Co., and gave up his job with the Pennsylvania Railroad.

As well as having good business sense, Andrew Carnegie possessed charm and literary knowledge. However, because of his humble and foreign birth, he was never fully accepted by Pittsburgh society. By 1868, when he moved permanently to New York City, his multiple investments were all nearly profitable; he owned assets of $400,000 and an annual income of over $56,000 at a time when a factory foreman earned $1000.

He seriously considered retiring at the age of thirty-five.

Carnegie and Steel

In the 36 years that followed his taking over the Kloman Co., Carnegie's career could serve as a summary of the industrial development of the nation in this period. In 1873, on one of his frequent trips to Great Britain, he met Henry Bessemer, inventor of the "Bessemer process," and became convinced that the industrial future lay in steel. His key decision investing $250,000 in the Edgar Thomson Steel Company, formed in 1874 with a capital of $1 million.

The Bessemer plant at the company's site at Braddock's Field, near Pittsburgh, was designed to manufacture high-quality steel rails. Carnegie's huge success with this venture was due first to his commitment to technological change and second to his previous experience with the railroads. He wanted to have the most modern equipment available and was willing, whenever necessary, to scrap expensive machinery after only a short time if better technology could be had.

The administrative structure he put together at the Edgar Thomson Works was similar to the one he had worked in at the Pennsylvania Railroad. He appointed the country's most talented steel engineer, Captain William Jones (1839-1889), as general superintendent to oversee the daily work of the managers in charge of the blast furnaces. Jones had invented several basic tools, such as the "Jones Mixer." Carnegie frequently pressured Jones to decrease employee wages, only to have Jones fearlessly reiterate the efficacy of enlightened labor policy.

Andrew Carnegie purchased iron ore lands in the Lake Superior region, acquired ships and ore-handling facilities, and joined forces in 1884 with Henry Clay Frick (1849–1919), who controlled the great Connesville coal beds. He formed Carnegie Bros. & Co. in 1881 with a capital of $5 million; its chairman was Tom Carnegie; after 1889, Frick held the post. Andrew Carnegie himself had no title, though he controlled 55% of the capital in the partnership, which made a profit of $2 million in its first year.

The Carnegie Steel Company, by 1900, had become an immense organization with a profit of $40 million that year. It included all the processes of steel production, from the great blast furnaces and finishing mills of Pittsburgh to the railroads and lake steamers that move the ores and the finished products.

Andrew Carnegie sold out his steel and related interests for $447 million in 1901 (Carnegie himself took $226 million; the rest went to his associates) to a syndicate formed by J. P. Morgan to create the United States Steel Company, by far the largest industrial corporation of the day

After 1868, he made New York City his base and seldom visited Pittsburgh, leaving daily operations in the hands of partners and senior subordinates. Carnegie always maintained that the secret of his business success lay not in his own genius as a maker of steel but in his ability to select the proper man for the job to be done.

He was one of the first industrialists to hire scientists for research, and he suggested for his own epitaph, "Here lies a man who was able to surround himself with men far cleverer than himself." Andrew Carnegie hired the best steelmakers, his own brother, Thomas M. Carnegie (1843–1886) (who died young), Henry Clay Frick, Charles M. Schwab, and the person he considered the greatest steelman of them all, Capt. "Bill" Jones.

Andrew Carnegie was not at home inside the factory. He did best 500 miles away, selecting and backing the experts, going over the accounts sent by telegraph every day to look for cost savings, and visiting bankers and financiers to sell bonds and railroads to sell rails and bridgework.

He was the greatest salesman of his day because he understood how his firm could best serve his customer's needs. For example, he worked with the brilliant civil engineer James Eads (1820–87), whose "Eads Bridge" across the Mississippi River at St. Louis, Missouri, symbolized the interrelationship of steel, railroads, and high finance during the Gilded Age.

To build his great bridge, Eads relied on Carnegie to supply high-quality steel, meet urgent deadlines, give bridge-building counsel, and provide the financial acumen that became essential for raising large sums of money for Eads to finally complete his bridge in 1874.

Carnegie was a visionary who studied philosophy and believed that the inevitability of evolution and progress depended on the right genius at the right time. His faith in America as a land of business opportunity never wavered; much of the fast growth of his steel enterprise was due to his policy of expanding in periods of depression.

He distrusted the ever-growing tendency of American business toward trust-building and overcapitalization, and the Carnegie Steel Co. remained a simple partnership arrangement greatly undercapitalized in terms of the actual value of its holdings and its annual profits.

Andrew Carnegie prided himself on his enlightened labor policy, although his reputation for benevolence was publicly damaged by the tragic Homestead Strike of 1892. It began when company manager Henry Clay Frick sought to impose a wage cut (which Carnegie had approved). When the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel, and Tin Workers refused his terms and called a strike on June 29, Frick brought in about 300 Pinkerton detectives to protect workers who remained on the job.

On July 6, an all-day armed clash occurred between strikers and detectives, in which strikers trapped a barge load of Pinkertons crossing the river and killed seven. The governor sent in 8500 militia to protect the plants and workers inside from further attacks by strikers.

Under militia protection, nonunion laborers manned the steel mills from July 12 to November 20, when the strike collapsed. Frick's success permanently weakened unionism in the entire steel industry, which was not unionized successfully until the 1930s. Union members blamed Carnegie for the episode.

Andrew Carnegie was originally favorable toward the union in the 1870s and 1880s because it did not threaten profitability and helped guarantee steady production. It became the largest labor union in the country. In 1886, he published a series of articles in the Forum magazine that revealed his liberal position on labor policies and benevolence toward his workers.

Philanthropy

'The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced,' declared Andrew Carnegie, a doctrine that received its fullest expression in his book The Gospel of Wealth (1900). In his view, plutocracy such as his could exist alongside democracy, but men who acquired great wealth must return it to the community to preserve individual initiative. Thus, the wealthy were but a trustee and an agent for their poorer brethren, albeit of the better and aspiring sort.

His "scientific philanthropy" was to be carefully targeted according to a list of seven priorities. These were headed by his overriding concerns, universities, and free libraries, with churches in seventh place (an indication of his hostility to organized religion).

The main instrument was the Carnegie Corporation, formed in 1911; it was a scientifically designed organization with regular, firmly-stated policies; it served as a model that replaced the paternalistic basis of American philanthropy based on the personal tastes, local connections, and whims of the philanthropist.

In spite of his espousal of Herbert Spencer's philosophy and portions of the social Darwinism of the period, Carnegie remained deeply committed to many of the Chartist ideals of his boyhood. He rejected Spencer's attacks on philanthropy. In 1868, when, at the age of 33, his personal income had already reached $50,000 annually, he had written himself a note vowing to quit business shortly and never earn more than he was then earning, for "the amassing of wealth is one of the worst species of idolatry."

He did not keep this resolution, but as his fortune grew, so did his concern for reconciling great wealth with social and political democracy. Out of this concern came his own solution in his famous "Gospel of Wealth," first published in The North American Review in 1889.

Here, Carnegie stated his doctrine concerning the responsibility of the man of wealth to society. He must use the fortune he has earned to provide greater opportunity for all and to increase man's knowledge of himself and of his universe.

In the 18 years after he retired from steel, he succeeded in giving back to society over $300,000,000, largely through the creation of one of the most remarkable groups of philanthropic foundations in the world. These foundations included, in Great Britain:

- The Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland

- The Carnegie Dunfermline Trust

- The Carnegie Hero Fund Trust

- The Carnegie United Kingdom Trust

- The Carnegie Institute of Pittsburgh

- The Hero Fund Commission

- The Carnegie Institute of Washington

- The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching

- The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- The Carnegie Corporation of New York

The Carnegie Teachers' Pension Fund (now TIAA) created a pension system for college professors with an endowment of $10 million. To be eligible, a college had to separate itself from control by a religious denomination, and many did so.

Carnegie was a large benefactor of the Tuskegee Institute for African-American Education under Booker T. Washington. He helped Washington create the National Negro Business League.

Carnegie Libraries

Carnegie's interest in libraries dates back to his early days as a messenger boy in Pittsburgh, when each Saturday, he borrowed a new book from a free library. He later declared that it was his own personal experience that led him to value a library beyond all other forms of beneficence. His first gift was a library to his native town of Dunfermline in 1882.

In 1898, he built The Carnegie Library in Homestead, Pennsylvania. Besides a library, the building included a bowling alley, an indoor swimming pool, basketball courts, other athletic facilities, a music hall, and space for a large number of meeting rooms for local clubs and organizations.

Carnegie systematically funded 2,507 libraries throughout the English-speaking world, including 1,689 libraries in the United States, 600 libraries in Great Britain, 66 in Ireland, and 125 in Canada. James Bertram, Carnegie's chief aide from 1894 to 1914, administered the library program, issued guidelines, and instituted an architectural review process.

As VanSlyck (1989) shows, the last years of the 19th century saw acceptance of the idea that libraries should be available to the American public free of charge. However, the design of the idealized free library was at the center of a prolonged and heated debate. On the one hand, wealthy philanthropists favored buildings that reinforced the paternalistic metaphor and enhanced civic pride.

They wanted a grandiose showcase that created a grand vista through a double-height, alcoved book hall with domestically-scaled reading rooms, perhaps dominated by the donor's portrait over the fireplace. Typical examples were the New York Public Library and the Chicago Public Library.

Librarians considered that grand design inefficient and too expensive to maintain. Between 1886 and 1917, Carnegie reformed both library philanthropy and library design, encouraging a closer correspondence between the two.

The Carnegie buildings typically followed a standardized style called "Carnegie Classic": a rectangular, T-shaped, or L-shaped structure of stone or brick, with rusticated stone foundations and low-pitched, hipped roofs, with space allocated by function and efficiency.

His libraries served not only as free circulating collections of books, magazines, and newspapers but also provided classrooms for growing school districts, Red Cross stations, and public meeting spaces, not to mention permanent jobs for the graduates of newly formed library schools. Academic libraries were built for 108 colleges. Usually, there was no charge to read or borrow; in New Zealand, however, local taxes were too low to support libraries, and most charged subscription fees to their users.

The arrangements were always the same: Carnegie would provide the funds for the building but only after the municipal government had provided a site for the building and had passed an ordinance for the purchase of books and future maintenance of the library through taxation. This policy was in accord with Carnegie's philosophy that the dispensation of wealth for the benefit of society must never be in the form of free charity but rather must be a buttress to the community's responsibility for its own welfare.

In 1901, Carnegie offered to donate $100,000 to the city of Richmond, Virginia, for a public library. The city council had to furnish a site for the building and guarantee that $10,000 in municipal funds would be budgeted for the library each year. Despite the support from the majority of Richmond's civic leaders, the city council rejected Carnegie's offer.

A combination of aversion to new taxes, fear of modernization, and fear that Carnegie might require the city to admit black patrons to his library account for the local government's refusal. In 1903, union leaders in Wheeling, West Virginia, blocked the acceptance of a Carnegie library there.

The Detroit Library subsisted on library fines and inadequate city funds; Carnegie offered $750,000 in 1901 but was turned down because it was "tainted money"; after nine more years of underfunding, Detroit took the money.

Legacy

His major trusts and foundations continue in operation in the 21st century, including the Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland, the Carnegie Dunfermline Trust, the Carnegie Institute, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission, the Carnegie Institution of Washington, the Carnegie Corporation and Carnegie-Mellon University. The Carnegie Corporation of New York, with a capital fund of $3.0 billion, remains a force in philanthropy at the rate of $100 million a year and still supports libraries.

Andrew Carnegie died on August 11, 1919, in Lenox, Massachusetts, at his Shadow Brook estate, of bronchial pneumonia. He had already given away $350,000,000 of his wealth. This would have been equal to $76.9 billion in modern currency.

His last $30,000,000 was given to foundations, charities, and pensioners.