The Battle of Bunker Hill is one of the most studied battles during the American Revolution. Despite it being a victory for the British the colonists stood their ground and decimated two assaults before retreating.

Also Read: 30 Most Famous Revolutionary War Battles

The battle also displays British soldier bravery and British officer snobbery. The British soldiers made three approaches and despite taking heavy casualties formed again for a third and had to march over dead bodies and wounded soldiers.

British officers underestimated the resolve and effectiveness of the colonists. They were fighting for their land and future and many stood and fought despite the high desertion rates.

Jump to:

- 1. Breed's Hill Not Bunker Hill

- 2. The British Were Under Siege

- 3. Generals William Howe, Henry Clinton, and John Burgoyne Arrived in Boston for Reinforcements

- 4. The Plan was to Take Dorchester Heights

- 5. Colonel William Prescott Secured Breed's Hill

- 6. The Colonials Took the First Casualty

- 7. British Commanders Disagreed On the Attack Plans

- 8. The British Finalized Their Plan

- 9. Joseph Warren and Seth Pomeroy Served As Privates

- 10. William Howe's Delay Created a Missed Opportunity

- 11. The Colonials Were Terribly Unorganized Prior To The Battle

- 12. The First British Assault Was a Disaster

- 13. Second Assault was again Devastating to the British

- 14. Confusion Overtook Both Sides

- 15. The Final Assault was Successful for the British

- 16. Joseph Warren and John Pitcairn were Killed in the Final Assault

- 17. John Stark and Thomas Knowlton led an Orderly Retreat

- 18. Thomas Gage was Dismissed and George Washington was made Commander-in-Chief

- 19. King George became Hardened and Rejected the Olive Branch Petition

- 20. African-Americans Fought For America During The Battle

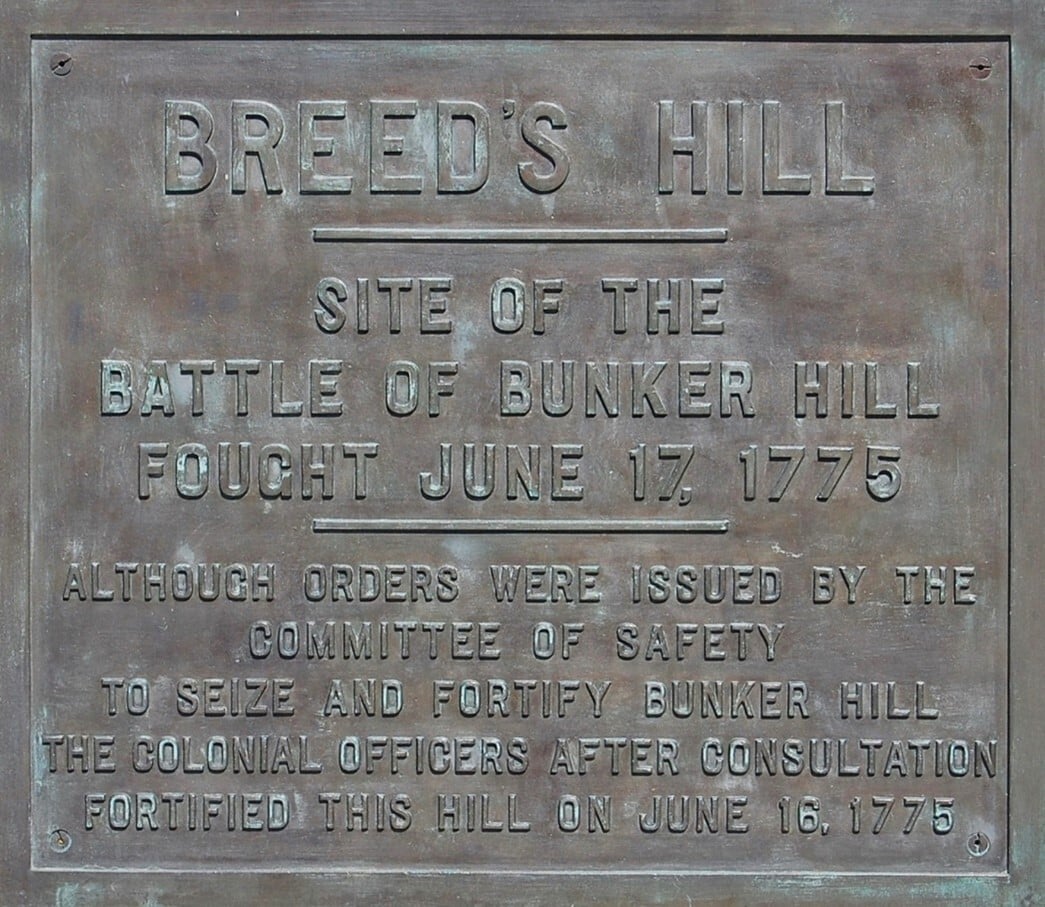

1. Breed's Hill Not Bunker Hill

The battle is known as the Battle of Bunker Hill, but the battle was not fought on Bunker Hill but rather on Breed's Hill.

There was a debate as to which hill should be defended and William Prescott chose Breed's Hill because he believed it to be a more advantageous position.

The reason it became known as the Battle of Bunker Hill was due to a British mistake that confused the two hills. Over time the name Breed's Hill faded away and only Bunker Hill was remembered.

A monument now sits on Bunker Hill which was not the spot of the battle.

Any man located on Bunker Hill was only there in confusion.

2. The British Were Under Siege

The colonial militia had the British under siege.

The British were not surrounded due to their backs being up against the ocean and the colonials did not have a navy. Supplies could continue to come in as well as men, but the colonials held an advantageous position which the British could not break without reinforcements.

The British had been placed under siege after their hasty retreat during the Battles of Lexington and Concord.

Also Read: Facts About Battles of Lexington and Concord

During their retreat from Lexington and Concord, the British were nearly cut off. If not for well-times reinforcements they would have sustained many more losses as they had grossly underestimated what they were up against.

3. Generals William Howe, Henry Clinton, and John Burgoyne Arrived in Boston for Reinforcements

They arrived on the HMS Cerberus and were dispatched to Boston to put down the rebellion. They arrived on May 25 and received General Thomas Gage into their ship to hear the current status of Boston and to then plan their attack.

These three Generals would serve throughout the war with only General Henry Clinton seeing it to the end.

General William Howe had sympathies toward the patriots, but he was dedicated to his country it would not affect his decisions. He was a brilliant commander and General Washington would struggle against him.

General John Burgoyne was known as "Gentleman Johnnie" and was loved by his men. He was known for his confidence, but that would be his downfall in the American theatre.

General Henry Clinton was known as a quiet officer who came as Howe's second in command. The two would eventually grow apart and he would be replaced by General Cornwallis. After Howe was recalled Clinton took over command.

These three were given orders to take control of Boston and would eventually be fighting the entire rebel army.

4. The Plan was to Take Dorchester Heights

When the three generals arrived they took a look at the terrain and probably heard analysis from Thomas Gage. It became clear that Dorchester Heights was key to taking control of the city and thus ending the rebellion.

This plan began with taking the Dorchester Neck, fortifying Dorchester Heights, and then marching on the colonial forces stationed in Roxbury. Once the southern flank had been secured, the Charlestown Heights would be taken, and the forces in Cambridge driven away.

The attack was set for June 18.

Unfortunately for the British, some men from New Hampshire overheard the plan and relayed it to the rebels. The colonials would begin to prepare immediately.

5. Colonel William Prescott Secured Breed's Hill

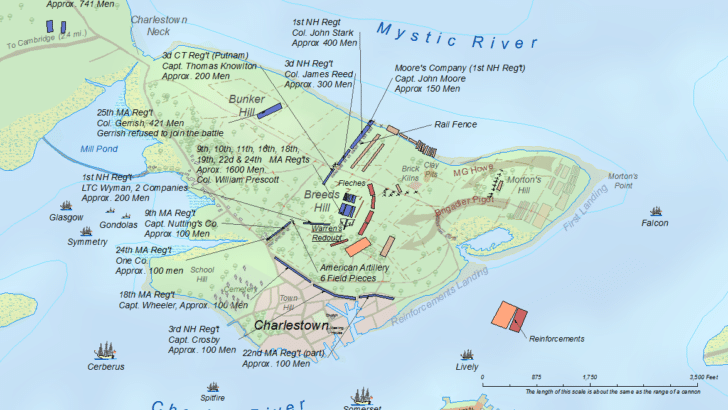

On the night of June 16, 1775, Colonel William Prescott led about 1,200 colonial soldiers onto the Charlestown peninsula to build fortifications. The soldiers were from the regiments of Prescott, Putnam, Frye, and Bridge.

At first, Putnam, Prescott, and their engineer Captain Richard Gridley disagreed about where to build the fortifications. They considered Bunker Hill but decided that Breed's Hill was closer to Boston and more defensible.

They began digging a square fortification about 130 feet on a side, with ditches and earthen walls. The walls were about 6 feet high, with a wooden platform inside on which the soldiers could stand and fire over the walls.

The construction of the fortifications was a risky move. The British were occupying Boston, and the soldiers were in plain sight of the British ships in the harbor. However, the soldiers worked quickly, but their work could be heard by General Henry Clinton and British soldiers.

The works on Breed's Hill did not go unnoticed by the British. General Clinton was out on reconnaissance that night and was aware of them, and he tried to convince Gage and Howe that they needed to prepare to attack the position at daylight.

Howe was not concerned with the construction.

6. The Colonials Took the First Casualty

When the British woke and saw everything the colonials had done their navy began to fire on the position of the patriots.

The British ships bombarded the colonial fortifications on Breed's Hill, but the bombardment had relatively little effect. The hilltop fortifications were too high for the ships to aim accurately, and they were too far from Copp's Hill for the batteries there to be effective.

However, the few shots that did manage to land killed one American soldier and damaged the entire supply of water for the troops.

Prescott ordered that the man be buried quickly and quietly fearing that if others saw a dead man this soon they would desert.

The men did not listen and had a 6-hour funeral which resulted in some men deserting.

7. British Commanders Disagreed On the Attack Plans

The British generals met to discuss their options for attacking the colonial fortifications on Breed's Hill. General Clinton argued that they should attack as soon as possible, and he preferred an attack from the Charlestown Neck.

This would have cut off the colonists' retreat, and the British could have starved out the occupants of the redoubt. However, the other three generals were concerned that this plan would violate the convention of the time, which was to avoid getting trapped between enemy forces.

In the end, the three generals outvoted Clinton, and they decided to attack the redoubt from the front. This was a riskier plan, but they believed their troops were superior and the untrained rebels would not be able to stand firm against their disciplined troops

8. The British Finalized Their Plan

General Gage surveyed the works from Boston with his staff, and Loyalist Abijah Willard recognized his brother-in-law Colonel Prescott. "Will he fight?" asked Gage. "As to his men, I cannot answer for them," replied Willard, "but Colonel Prescott will fight you to the gates of hell."

It took six hours for the British to organize an infantry force and to gather up and inspect the men on parade. General Howe was to lead the major assault, driving around the colonial left flank and taking them from the rear.

Brigadier General Robert Pigot on the British left flank would lead the direct assault on the redoubt, and Major John Pitcairn would lead the flank or reserve force.

It took several trips in longboats to transport Howe's initial forces to the eastern corner of the peninsula, known as Moulton's Point.

By 2 p.m., Howe's chosen force had landed. However, while crossing the river, Howe noted the large number of colonial troops on top of Bunker Hill.

He believed these to be reinforcements and immediately sent a message to Gage, requesting additional troops.

He then ordered some of the light infantry to take a forward position along the eastern side of the peninsula, alerting the colonists to his intended course of action. The troops then sat down to eat while they waited for the reinforcements.

9. Joseph Warren and Seth Pomeroy Served As Privates

Joseph Warren had been given a commission to be Major General and when he showed up to fight alongside the other soldiers William Prescott and Israel Putnam asked him to lead them, but he refused believing the other two had more experience.

Seth Pomeroy, who was an older Massachusetts militia leader, also arrived to fight as a private. He did not care about rank either.

Warren was probably a boost to morale as he was well-known and popular. They along with others would join to help reinforce the colonial position.

10. William Howe's Delay Created a Missed Opportunity

If Howe had followed Clinton's advice then he would have attacked the colonials prior to reinforcements making it to Breed's Hill.

The most notable addition to the reinforcements was John Stark and James Reed.

Stark's men did not arrive until after Howe landed his forces, and thus filled a gap in the defense that Howe could have taken advantage of, had he pressed his attack sooner.

They took positions along the breastwork on the northern end of the colonial position. Low tide opened a gap along the Mystic River to the north, so they quickly extended the fence with a short stone wall to the water's edge.

Colonel Stark placed a stake about 100 feet in front of the fence and ordered that no one fire until the British regulars passed it.

Further reinforcements arrived just before the battle, including portions of Massachusetts regiments of Colonels Brewer, Nixon, Woodbridge, Little, and Major Moore, as well as Callender's company of artillery.

11. The Colonials Were Terribly Unorganized Prior To The Battle

Behind the colonial lines, confusion reigned. Many units sent to the action stopped before crossing the Charlestown Neck from Cambridge, which was under constant fire from gun batteries to the south.

Others reached Bunker Hill, but then were uncertain where to go from there and just milled around.

One commentator wrote of the scene that "it appears to me there never was more confusion and less command."

General Israel Putnam was on the scene attempting to direct affairs, but unit commanders often misunderstood or even disobeyed orders. This led to a lack of coordination and a general sense of chaos.

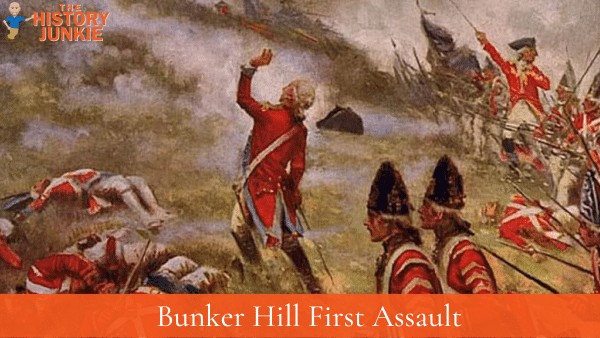

12. The First British Assault Was a Disaster

By 3 p.m., the British reinforcements had arrived, and they were ready to march. Brigadier General Pigot's force was gathering just south of Charlestown village, where they were already taking casualties from sniper fire.

Admiral Graves ordered a landing party to set fire to the town, which created a surreal backdrop to the fighting.

General Howe led the light infantry companies and Grenadiers in the assault on the American left flank along the rail fence. He expected an easy effort against Stark's recently arrived troops, but the colonists withheld their fire until the regulars were within 50 paces.

The colonists benefited from the rail fence to steady and aim their muskets, and they enjoyed cover from return fire. Under this withering fire, the light companies melted away and retreated.

Pigot's attacks on the redoubt and breastworks fared little better. By stopping and exchanging fire with the colonists, the regulars were fully exposed and suffered heavy losses. They continued to be harried by snipers in Charlestown, and Pigot ordered a retreat after seeing what happened to Howe's advance.

James Abercrombie was fatally wounded in the assault.

13. Second Assault was again Devastating to the British

The regulars reformed on the field and marched out again, this time navigating a field strewn with dead and wounded comrades.

This time, Pigot was not to feint; he was to assault the redoubt directly, possibly without the assistance of Howe's force.

Howe advanced against Knowlton's position along the rail fence, instead of marching against Stark's position along the beach.

The outcome of the second attack was very much the same as the first. One British observer wrote, "Most of our Grenadiers and Light-infantry, the moment of presenting themselves lost three-fourths, and many nine-tenths, of their men.

Some had only eight or nine men a company left." Pigot's attack did not enjoy any greater success than Howe, and he ordered a retreat after almost 30 minutes of firing ineffective volleys at the colonial position.

The second attack had failed.

14. Confusion Overtook Both Sides

After the second assault, confusion escalated in the rear of the colonial forces.

General Putnam tried to send additional troops from Bunker Hill to the forward positions on Breed's Hill, but his efforts were met with limited success.

Some companies and leaderless groups of men moved toward the field, while others retreated. The colonial regiments were running low on powder and ammunition, and many soldiers had deserted.

By the time the third British attack came, there were only 700-800 men left on Breed's Hill, with only 150 in the redoubt.

The British rear was also in disarray. Wounded soldiers were being ferried back to Boston, while the wounded lying on the field of battle were moaning and crying in pain.

Howe sent word to Clinton in Boston for additional troops. Clinton had observed the first two attacks and sent around 400 men from the 2nd Marines and the 63rd Foot, and followed himself to help rally the troops.

In addition to these reserves, he convinced around 200 walking wounded to form up for the third attack.

15. The Final Assault was Successful for the British

The third British attack was to focus on the redoubt, with only a feint on the colonists' flank. Howe ordered his men to remove their heavy packs and leave all unnecessary equipment behind.

He arrayed his forces in column formation, rather than the extended order of the first two assaults, which would expose fewer men along the front to colonial fire.

The third attack was made at the point of the bayonet and successfully carried the redoubt.

The defenders had run out of ammunition, reducing the battle to close combat.

The advantage turned to the British, as their troops were equipped with bayonets on their muskets, while most of the colonists were not.

The colonists were forced to retreat.

16. Joseph Warren and John Pitcairn were Killed in the Final Assault

During the retreat, Joseph Warren took a musket ball to the head and died instantly. In a fury, the British stipped him, bayoneted his body beyond recognition, and buried him in a shallow grave.

In a letter to John Adams, Benjamin Hichborn describes the damage that British Lieutenant James Drew, of the sloop Scorpion, inflicted on Warren's body two days after the Battle of Bunker Hill: "In a day or two after, Drew went up on the Hill again opened the dirt that was thrown over Doctor Warren, spit in his face jumped on his stomach and at last cut off his head and committed every act of violence upon his body."

His body was exhumed ten months after his death by his brothers and Paul Revere, who identified the remains by the artificial tooth he had placed in the jaw.

His death would make him a martyr for the cause.

The Patriots were not alone in a significant loss during the final assault. Major John Pitcairn was also killed. He had served during the Battles of Lexington and Concord and was loved by his men.

17. John Stark and Thomas Knowlton led an Orderly Retreat

The retreat of much of the colonial forces from the peninsula was made possible in part by the controlled withdrawal of the forces along the rail fence, led by John Stark and Thomas Knowlton, which prevented the encirclement of the hill.

Burgoyne described their orderly retreat as "no flight; it was even covered with bravery and military skill". It was so effective that most of the wounded were saved; most of the prisoners taken by the British were mortally wounded.

General Putnam attempted to reform the troops on Bunker Hill; however, the flight of the colonial forces was so rapid that artillery pieces and entrenching tools had to be abandoned.

The colonists suffered most of their casualties during the retreat on Bunker Hill.

By 5 p.m., the colonists had retreated over the Charlestown Neck to fortified positions in Cambridge, and the British were in control of the peninsula.

Despite taking control the losses were tremendous and the victory would be considered a pyrrhic victory.

18. Thomas Gage was Dismissed and George Washington was made Commander-in-Chief

The battle changed leadership on both sides.

It was imminent that Thomas Gage was going to be relieved of his command, but after the defeat, he wrote a report that angered many in England. This led to his dismissal and his return to England with his wife Margaret Kemble Gage.

Also Read: Famous Revolutionary War Generals

On the American side, it led to the promotion of George Washington to Commander-in-Chief. He would take over command in Boston and relieve Artemis Ward. This would unify the colonies and give them the ability to raise additional troops.

Washington would begin to bring a sense of order to the rag-tag colonists, but he would have to deal with many independent militia groups.

19. King George became Hardened and Rejected the Olive Branch Petition

King George III became irate after learning about the battle and when he received the Olive Branch Petition he quickly rejected it.

Also Read: Reasons the Olive Branch Petition Failed

What King George did not know was that many southern colonies and a couple of middle colonies were still on the fence about independence and were looking for an opportunity to rejoin the Mother Country.

His rejection of the petition and his Proclamation afterward pushed the rest of the colonies toward independence.

Within a year the Continental Congress had written, signed, and ratified the Declaration of Independence.

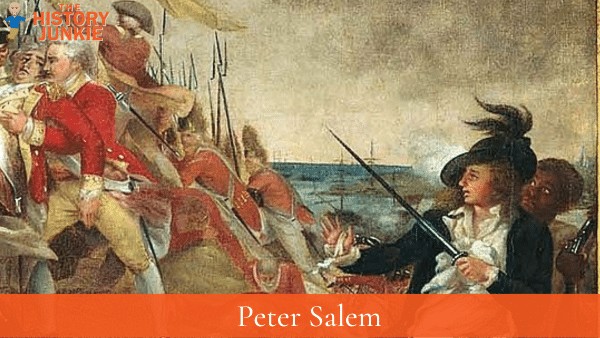

20. African-Americans Fought For America During The Battle

A forgotten fact was that there were many free black men who fought for the colonists during the Battle of Bunker Hill.

These men include Less well-known were the approximately three dozen African-American soldiers including Barzillai Lew, Phillip Abbot (who died in action), Alexander Ames, Isaiah Bayoman, Cuff Blanchard, Titus Coburn, Grant Cooper, Caesar Dickenson, Charlestown Eaads, Alexander Eames, Asaba Grosvenor, Blaney Grusha, Jude Hall, Cuff Haynes, Cato Howe, Caesar Jahar, Pompy of Braintree, Salem Poor, Caesar Post, Job Potama, Robin of Sandowne, New Hampshire, Peter Salem, Seasor of York County, Sampson Talbot, Cato Tufts, and Cuff Whitemore, who also took part in the battle.

Slavery did exist in Massachusetts at the time, but it was not common nor did the economy depend on it. It was abolished in 1783.

Many of these men were workers who worked as ropemakers or in the fishing industry.

The image above is a historic photo that shows the death of Joseph Warren. It also depicts the death of John Pitcairn of the British who is also in the picture mortally wounded against two British soldiers. His eyes are looking at the African-American who is behind a militia officer.

This black man was Peter Salem who from eyewitness accounts was the man who put a bullet in the head of Pitcairn.