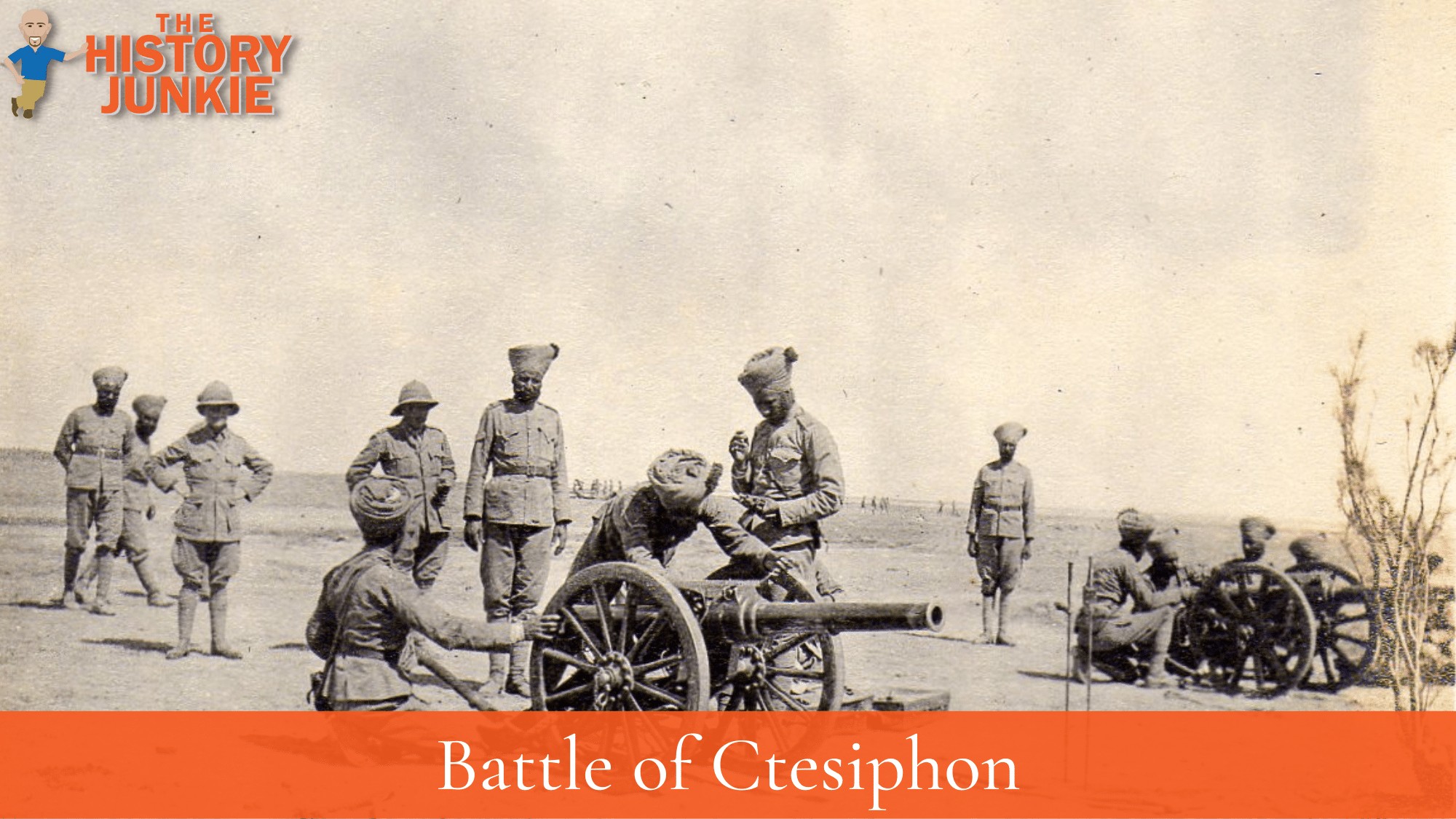

After a year of successes at Basra, Qurna, Shaiba, Amara, Nasiriyeh, and Kut, British forces suffered a major defeat at the Battle of Ctesiphon, which took place from November 22 - 25, 1915, in World War 1.

After occupying Kut in November 1915, British Commander-in-Chief in Mesopotamia, Sir John Nixon, ordered Sir Charles Townshend, commander of the 6th Indian Division, to advance on Baghdad.

Jump to:

Prelude

Townshend argued against further extending the British supply line, which was already over 600 kilometers long and tenuous.

He requested more transport and trench warfare equipment before advancing, but Nixon disagreed, so Townshend went ahead with the push forward.

Nixon was backed by the eager support of the Indian government, which had appointed him in the first place.

The British government in London was more reluctant but eventually agreed to the plan when they saw how eager India was.

The Turks, following their defeat at Kut, had retreated to carefully prepared defensive positions among the ancient ruins of Ctesiphon.

This was their forward defense of Baghdad, which was Nixon's real goal.

When Nixon ordered Townshend to advance, the Turks had already constructed two lines of deep trenches on either side of the Tigris River.

They were defended by some 18,000 experienced troops. Townshend had only about 11,000 Anglo-Indian troops, and there were no plans to send him any reinforcements.

The British government was eager for a major victory on the Mesopotamian Front. Even though capturing Baghdad would have no great strategic value, it would be a propaganda coup.

Baghdad is one of the four great cities of Islam, and its capture would be a major morale boost for the British people after the failure at Gallipoli.

The Battle

On November 22, 1915, Townshend's force, aided by the newly-arrived monitor Firefly and a shallow-draft gunboat, initiated operations against Nur-Ud-Din.

Aware of the impracticality of launching a dual attack on both sides of the river at once, due to a shortage of men and poor ground conditions on one side, Townshend decided to concentrate his attack on the east bank.

Specifically, he chose to repeat his earlier success at Kut-al-Amara by issuing orders for night-marching, with the aim of surprising the Turkish defenders in a flank attack.

Unfortunately, many of Townshend's forces got lost in the dark, which ruined the element of surprise. The British attack foundered while negotiating the Turkish second-line defenses.

Unlike in earlier encounters, Townshend was unable to call upon naval support because of the Turks' extensive deployment of mines and artillery.

On the following day, November 23, Turkish forces launched a mild counter-attack in an attempt to reclaim their front-line positions.

Although the counter-attack failed, Townshend's casualty rate was increasing at an alarming rate.

Uneasy by both the Turks and the marsh Arabs, Townshend's tired force eventually retreated to Kut on December 3rd.

Aftermath

They were preceded by makeshift hospital ships, which operated in highly unsanitary conditions. Townshend also lost his warships during the retreat, which were sunk by Turkish shore batteries.

Once at Kut, Townshend began preparations for its defense, pending reinforcements from Basra. Both the British and Indian governments were shocked by the resilience of the Turkish defenders at Ctesiphon.

They resolved to send reinforcements to Mesopotamia to assist Townshend, and the British government began to consider treating the Mesopotamian and Palestine Fronts as a single theater of war.