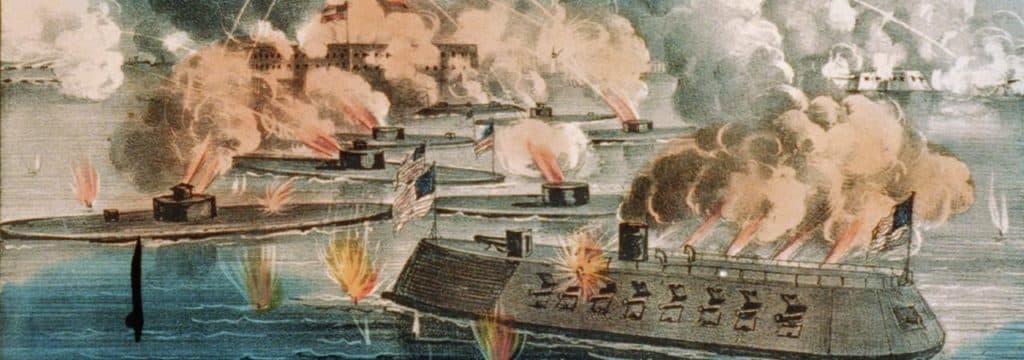

The Battle of Fort Sumter (April 12–13, 1861) was the bombardment of Fort Sumter near Charleston, South Carolina, by the Confederate Army and is recognized as the official start of the Civil War. The battle occurred after a declaration of secession by South Carolina on December 20, 1860. Once South Carolina seceded, they demanded that the United States Army abandon its facilities in Charleston Harbor. In response, Major Robert Anderson moved his army from Fort Moultrie from Sullivan's Island to Fort Sumter, a substantial fortress built on an island controlling the entrance of Charleston Harbor. An attempt by U.S. President James Buchanan to reinforce and resupply Anderson using the unarmed merchant ship Star of the West failed when it was fired upon by shore batteries on January 9, 1861. South Carolina authorities then seized all Federal property in the Charleston area except for Fort Sumter.

Learn If Your Ancestor's Fought at Fort Sumter

Jump to:

Beginning

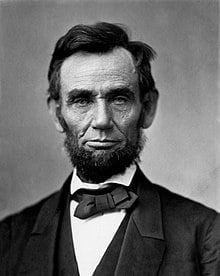

After Abraham Lincoln won the election of 1860, the South reached their breaking point. South Carolina became the first state of the union to secede from the United States and quickly demanded the removal of all federal military from their state. The removal was refused, and shortly after, South Carolina fired the first shots of the Civil War.

The Forts in Charleston were weak in their land defense due to being built for defense from the sea. This weakness was exploited by the Confederacy when it opened fire on the forts.

Fort Sumter dominated the entrance to Charleston Harbor and, though unfinished, was designed to be one of the strongest fortresses in the world. In the fall of 1860, work on the fort was nearly completed, but the fortress was thus far garrisoned by a single soldier, who functioned as a lighthouse keeper and a small party of civilian construction workers. Under cover of darkness on December 26, six days after South Carolina declared its secession, Anderson abandoned the indefensible Fort Moultrie, ordering its guns spiked and its gun carriages burned, and surreptitiously relocated his command by small boats to Sumter.

Lincoln and War

President Buchanan handed the presidency over to Abraham Lincoln, who was greeted with the news of Fort Sumter and also Fort Pickens in Pensacola, Florida. Both forts reported low rations, and Lincoln was forced into making a decision to reinforce the fort and risk starting a war.

The new Confederate States of America were also split on how to go about Fort Sumter. Was it the decision of South Carolina or the newly formed government to decide what action was necessary?

The South sent delegations to Washington, D.C., and offered to pay for the Federal properties and enter into a peace treaty with the United States. Lincoln rejected any negotiations with the Confederate agents because he did not consider the Confederacy a legitimate nation, and making any treaty with it would be tantamount to recognition of it as a sovereign government.

On April 4, as the supply situation on Sumter became critical, President Lincoln ordered a relief expedition to be commanded by former naval captain Gustavus V. Fox, who had proposed a plan for nighttime landings of smaller vessels than the Star of the West. Fox's orders were to land at Sumter with supplies only, and if he was opposed by the Confederates, to respond with the U.S. Navy vessels following and to then land both supplies and men. This time, Maj. Anderson was informed of the impending expedition, although the arrival date was not revealed to him. On April 6, Lincoln notified Governor Pickens that "an attempt will be made to supply Fort Sumter with provisions only, and that if such attempt be not resisted, no effort to throw in men, arms, or ammunition will be made without further notice, [except] in case of an attack on the fort."

Lincoln's notification had been made to the governor of South Carolina, not the new Confederate government, which Lincoln did not recognize. Pickens consulted with Beauregard, the local Confederate commander. Soon, President Davis ordered Beauregard to repeat the demand for Sumter's surrender and, if it did not, to reduce the fort before the relief expedition arrived. The Confederate cabinet, meeting in Montgomery, endorsed Davis's order on April 9. Only Secretary of State Robert Toombs opposed this decision: he reportedly told Jefferson Davis the attack "will lose us every friend at the North. You will only strike a hornet's nest. ... Legions now quiet will swarm out and sting us to death. It is unnecessary. It puts us in the wrong. It is fatal."

Beauregard dispatched aides, Col. James Chesnut, Col. James A. Chisholm, and Capt. Stephen D. Lee to Fort Sumter on April 11 to issue the ultimatum. Anderson refused, although he reportedly commented, "I shall await the first shot, and if you do not batter us to pieces, we shall be starved out in a few days." The aides returned to Charleston and reported this comment to Beauregard. At 1 a.m. on April 12, the aides brought Anderson a message from Beauregard: "If you state the time which you will evacuate Fort Sumter, and agree in the meantime that you will not use your guns against us unless ours shall be employed against Fort Sumter, we will abstain from opening fire upon you." After consulting with his senior officers, Maj. Anderson replied that he would evacuate Sumter by noon, April 15, unless he received new orders from his government or additional supplies. Col. Chesnut considered this reply to be too conditional and wrote a reply, which he handed to Anderson at 3:20 a.m.: "Sir: by authority of Brigadier General Beauregard, commanding the Provisional Forces of the Confederate States, we have the honor to notify you that he will open fire of his batteries on Fort Sumter in one hour from this time." Anderson escorted the officers back to their boat, shook hands with each one, and said, "If we never meet in this world again, God grant that we may meet in the next."

The Civil War's First Shots

At 4:30 AM, April 11, 1861, Lt. Henry S. Farley, acting on the command of Captain George S James, fired the first shots of the Civil War. The first shot was a signal to the others to begin fire. Soon, in a counter-clockwise motion with 2-minute intervals, 43 guns opened fire on Fort Sumter. The shelling of Fort Sumter from the batteries ringing the harbor awakened Charleston's residents (including diarist Mary Chesnut), who rushed out into the predawn darkness to watch the shells arc over the water and burst inside the fort.

Major Anderson held his fire and waited for night to fall. When night came, he would attempt to leave the fort peacefully, but the weather did not allow for that to happen. Unfortunately, Anderson did not have the manpower to man the 60 guns that were available, and since the fort was built for sea invasions, he did not have the proper cannons to fire at Fort Moultrie. He also did not want to risk casualties and did not place men on guns that would leave them exposed to enemy fire. Abner Doubleday fired the first shot in defense of the fort.

Although Sumter was a masonry fort, there were wooden buildings inside for barracks and officer quarters. The Confederates targeted these with Heated shots (cannonballs heated red hot in a furnace), starting fires that could prove more dangerous to the men than explosive artillery shells. At 7 p.m. on April 12, a rain shower extinguished the flames, and at the same time, the Union gunners stopped firing for the night. They slept fitfully, concerned about a potential infantry assault against the fort. During the darkness, the Confederates reduced their fire to four shots each hour. The following morning, the full bombardment resumed, and the Confederates continued firing hot shots against the wooden buildings. By noon, most of the wooden buildings in the fort and the main gate were on fire. The flames moved toward the main ammunition magazine, where 300 barrels of gunpowder were stored. The Union soldiers frantically tried to move the barrels to safety, but two-thirds were left when Anderson judged it was too dangerous and ordered the magazine doors closed. He ordered the remaining barrels thrown into the sea, but the tide kept floating them back together into groups, some of which were ignited by incoming artillery rounds. He also ordered his crews to redouble their efforts at firing, but the Confederates did the same, firing the hot shots almost exclusively. Many of the Confederate soldiers admired the courage and determination of the Yankees. When the fort had to pause its firing, the Confederates often cheered and applauded after the firing resumed, and they shouted epithets at some of the nearby Union ships for failing to come to the fort's aid.

Surrender of Fort Sumter

The Union garrison formally surrendered the fort to Confederate personnel at 2:30 p.m., April 13. No one from either side was killed during the bombardment. During the 100-gun salute to the U.S. flag, Anderson's one condition for withdrawal, a pile of cartridges blew up from a spark, mortally wounding privates Daniel Hough and Edward Galloway and seriously wounding the other four members of the gun crew; these were the first military fatalities of the war. The salute was stopped at fifty shots. Hough was buried in the Fort Sumter parade ground within two hours after the explosion. Galloway and Private George Fielding were sent to the hospital in Charleston, where Galloway died a few days later; Fielding was released after six weeks. The other wounded men and the remaining Union troops were placed aboard a Confederate steamer, the Isabel, where they spent the night and were transported the next morning to Fox's relief ship Baltic, resting outside the harbor bar.

Aftermath

The surrender of Fort Sumter sent shockwaves throughout the United States and Confederate States alike. Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers, which was filled immediately by some states while others were still reluctant to get involved. Patriotism on both sides had reached a high, and young men began preparing for a full-scale war. While the Battle of Fort Sumter did not have any casualties, it led to the bloodiest war in American History.

Fort Sumter would remain in Confederate hands throughout the war and would be the only hole in the Union Blockade. Several attempts were made to recapture the fort but ultimately failed until General Sherman outflanked the Fort in his march up the coast. The Confederates then abandoned the fort, and Major Anderson would return to raise the American flag that he had lowered.

Battle of Fort Sumter: Online Resources

- Wikipedia - Battle of Fort Sumter

- Fort Sumter National Monument

- Fort Sumter Tours

- Civil War Trust - Fort Sumter Information

- Telegram announcing the surrender of Fort Sumter

- Fort Sumter Attack to Surrender Telegrams

- Fort Sumter Facebook Page

- Allegiance: Fort Sumter, Charleston, and the Beginning of the Civil War

- Smithsonian - The Civil War Begins

- The History Junkie's Guide to the Civil War

- The History Junkie's Civil War Timeline

- The History Junkie's Guide to Civil War Genealogy

- Fort Sumter Ancestors