The Battle of Hampton Roads was a two-day naval engagement of the American Civil War, which took place on March 8–9, 1862, in the waters of Hampton, Virginia. This battle is remarkable for the first fight between two ironclad warships: USS Monitor and CSS Virginia.

After the battle ended, naval warfare had been changed forever.

Prelude

The status of the United States Navy in January 1861 was woeful. Years of bureaucratic ineptitude and red tape left the Navy in poor condition. The fleet consisted of 90 warships; of these, 48 ships were out of commission, and the rest, or in reality, the ones able to make steam or sail, were showing the flag in foreign seas.

Manning them were about 9,000 officers and men who were trained in the art of defending a harbor or ship-to-ship fights at sea, but not for the war that was just weeks away. As it were, President Abraham Lincoln had just three commissioned warships at his disposal, not much for the blockade of Southern ports he had declared on April 15.

Added to his woes were the names of 237 Naval officers who resigned their commissions and "headed south" as soon as secession in their respective states took place.

Southerners were not surprised nor disheartened by their own navy, meager as it were. The few vessels the new Confederacy had were revenue cutters seized from Federal port authorities during the secession.

Further, Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephan Mallory was progressive in matters of naval design; he had once been chairman of the Senate Naval Affairs Committee and had told the Southern cabinet that he professed interest in fast surface raiders to go after the Union Navy on the high seas, as well as proposing a very ugly craft that would change naval history:

I regard the possession of an iron-armored ship as a matter of the first necessity. Such a vessel at this time could traverse the entire coast of the United States, prevent all blockades, and encounter, with a fair prospect of success, their entire Navy.

On May 8, 1861, Mallory submitted his plans for building ironclads to the Confederate Committee on Naval Affairs, declaring that it would be costly, but the advantages of the Union Navy being overwhelmed by the sheer power implied in these untested vessels would be worth the price.

By the end of the month, the plans were approved, and the first ship selected for refitting was the salvaged hulk of USS Merrimac, scuttled the previous month when the Union abandoned Norfolk. She was placed in drydock, and over the next several months, the hull was razed to the gun deck, the engine overhauled, and a heavy-timber casemate was built over the hull and plated with four inches of sheet iron.

Inside the casemate were two 7-inch pivot guns at the bow and stern, three 9-inch smoothbore Dahlgrens, and one 6-inch Brooke rifled gun in each broadside. As a final weapon, a cast-iron ram weighing 1,500 pounds was fitted to the bow. The Confederacy would christen her CSS Virginia.

At about the same time the Merrimac was being overhauled, a naval committee was convened in Washington in August 1861, with Union Navy Secretary Gideon Welles presiding, and the discussion was also about ironclads.

Of seventeen submitted plans, two were accepted but without much enthusiasm for either: a large, sea-going steam frigate named New Ironsides and a smaller gunboat named Galena, designed by Cornelius Bushnell of New Haven, Connecticut.

That same night, Bushnell had taken his plans for Galena to a friend named John Ericsson, a Swedish inventor and engineer, who told him the plans were sound.

Ericsson then went to a cupboard and pulled a model of his own, a strange-looking flat vessel with a single, two-gun turret, and showed it to Bushnell. Convinced of this vessel's superiority, Bushnell took Ericsson before the board, who bickered back and forth until President Lincoln looked it over.

"All I have to say," he said, "is what the girl said when she put her foot in the stocking: 'It strikes me there's something in it!'" After a detailed explanation of his ship's qualities, Ericsson's plans for the USS Monitor were approved.

The First Day

On March 8, 1862, the blockading squadron in Hampton Roads was largely at anchor. Ships present included the 50-gun sail frigates St Lawrence and Congress; the 40-gun steam frigates Minnesota and Roanoke; the 24-gun sloop Cumberland; and the gunboat Zouave.

At about 12:30 in the afternoon, the watch on the Zouave spotted the Virginia heading their way. Also watching was a crowd of civilians on the south side of the Roads, eager to see the Union fleet sent to the bottom.

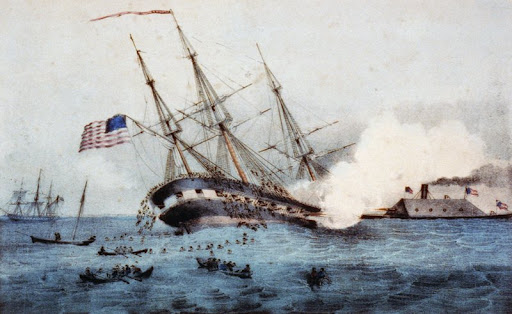

Attack on USS Cumberland

Captain Franklin Buchanan, Virginia's commanding officer, outlined his plans before his officers. They were ordered to break the blockade; they would attack and sink the two ships anchored near Newport News first (Cumberland and Congress), then she would turn to the east and go after the Minnesota and Roanoke near Fort Monroe.

Zouave fired first, its shells glancing off Virginia's armored hide. Buchanan ignored the smaller gunboat and continued on to the Cumberland, which also had fired on the ironclad to no effect. When Virginia closed within a mile, Buchanan ordered his bow gun fired; the first shot wounded several sailors on Cumberland, and a second shot tore a hole in the side, killing everyone but two at a forward gun mount.

As Virginia was taking fire from Cumberland, Congress, and the shore batteries at Newport News, Buchanan ordered full speed, intent on ramming Cumberland. A.B. Smith, the pilot of Cumberland, looked down with worried fascination at the ram, clearly visible in the water. "As she came plowing through the water toward our port bow," he said, "she looked like a half-submerged crocodile. At her prow, I could see the iron ram. It was impossible for our vessel to get out of her way."

Virginia tore a hole in Cumberland's side, deep enough to temporarily lock both ships together; the incoming current from the tide would release Virginia but, in so doing, would force the ram to break away and leave it inside Cumberland's hull.

Even as she sank, the crew kept at their guns and continued to give a withering rate of fire to the ironclad. She would sink in 54 feet of water, with her masts poking above the surface and her commanding officer refusing Buchanan's request to surrender.

Attack on USS Congress

The commanding officer of Congress, Lieutenant Joseph Smith, Jr., signaled to Zouave to tow the frigate into the shallow water near the shore; he knew the deep draft of Virginia would prevent her from reaching the frigate there.

However, Buchanan saw this and went after both, firing round after round into the ship's stern. Then Congress ran aground at an angle, preventing all but two of her 50 guns to be useful; Buchanan would soon put these out of action.

Then, a shot killed Smith, and seeing how helpless the ship was, the executive officer ran up a white flag. As Buchanan sent out boats to accept the surrender, the shore batteries continued to fire, and a sharpshooter put a bullet in his thigh.

Badly wounded, Buchanan ordered Congress set on fire by hotshot, cannonballs heated red-hot prior to loading in the guns. As Buchanan was carried below, his executive officer, Lieutenant Catesby Jones, took over command.

Jones then made a heading for Minnesota. which struggled to get herself off a shoal she had run aground on. By now, the pilots on Virginia had made a case to Jones that they themselves would run aground as a result of an ebb tide, and the sun was going down. Reluctantly, Jones abandoned the attack and headed back to Norfolk, intending to finish the battle in the morning.

Effect on Washington

The following morning, as news of the disaster was telegraphed north, President Lincoln called an emergency meeting of his cabinet. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton was worried. "The Merrimac will change the whole course of the war," he declared. "She will destroy, seriatum, every naval vessel; she will lay all the cities on the seaboard under contribution."

Afterward, he would fire off telegrams to the governors of all the states that shared the seacoast: "MAN YOUR GUNS. BLOCK YOUR HARBORS. THE MERRIMAC IS COMING!"

The Second Day

On March 9, Virginia again got underway and headed north into Hampton Roads, intending to finish off Minnesota and drive the remaining vessels from the area, and again, spectators lined Sewell's Point to watch the battle. As Jones and his crew neared their objective, a strange little vessel came out from behind the big frigate.

"No words can express the surprise with which we beheld this strange craft," wrote an observer in a rowboat, "whose appearance was tersely and graphically described by the exclamation of one of my oarsman, 'A tin can on a shingle!'"

The "tin can on a shingle" was USS Monitor, Ericsson's "folly," as Stanton called her, just arrived in Hampton Roads after a harrowing trip from New York in which she nearly sank twice and was guided into the Roads by the light of the burning Congress.

At 8:06 a.m., the Virginia opened fire, which passed over Monitor and struck Minnesota. When the distance between the two ironclads closed, Virginia turned her beam and fired a full broadside at Monitor's turret; the shot glanced harmlessly off and into the sea.

The men inside, thinking they were in a coffin a few minutes before, found renewed confidence. Lieutenant Dana Greene, Monitor's executive officer, wrote years later, "We believed the Merrimac would not repeat the work she had accomplished the day before."

Both ships then exchanged blows against each other for the next four hours, neither gaining an advantage over the other. The monitor had an advantage in speed and maneuverability, as well as her turret, which could be trained on Virginia without turning the whole ship, which her opponent had to do.

Further, Virginia's deep draft prevented her from being effective anywhere but the deep channels; at one point, she grounded for fifteen minutes as the crew frantically worked to increase the steam pressure to get her out of the mud, all the while being relentlessly pounded by Monitor's guns.

Then came a shot at Monitor's only weak point: its pilothouse. Lt Worden was leaning against the eye slits when the shot struck, sending shards into both eyes, blinding one permanently. Worden had to be taken below, and Greene took the helm of the ship, again preventing Virginia from attacking Minnesota.

As the tide was going out once more, Jones thought the better of it, brought Virginia about, and headed back to Norfolk.

Aftermath

This was their only fight together. Virginia would continue to be a threat to the blockading squadron in Hampton Roads, coming out once more on April 11 in an attempt to board Monitor, but fell back when the Union ship refused to leave the shallows near Fort Monroe, leaving Virginia to exchange a few shots with the shore batteries.

On May 10, Norfolk fell back into Union hands, and the retreating Confederates set fire to Virginia to prevent her capture. The Monitor would sink in a gale off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, on December 30 while under tow to Charleston, taking twelve of her crew with her.

Although the battle itself was a draw, the Union scored a strategic victory in that the primary mission of Virginia, that of breaking the blockade had failed. In a larger sense, the battle drove in a valid point, and nowhere was this felt more keenly than in Great Britain, home of the world's most powerful navy.

The Times of London lamented that before March 9, 1862, the Royal Navy had 147 powerful, first-rate ships; after March 9, they were down to two, Warrior and Ironside, both of them ironclads. The Battle of Hampton Roads made the rest of the Royal Navy, indeed every navy around the world, obsolete.