Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge Facts: Overview

Date of Battle: February 27, 1776

Region: Southern Colonies, Moore's Creek Bridge, North Carolina

Opposing Forces: British (Tories): 1,600 Americans: 1,000

British Perspective: Early Patriot successes in the North triggered an outbreak of sympathy in the Old North State that had led to the ouster of Josiah Martin, the Royal Governor of North Carolina. Martin initially sought refuge at Fort Johnston near Cape Fear. The rebels were determined to remove him from the colony, and so threatened, Martin fled for safety offshore on the British warship Cruizer.

Martin and other refugee officeholders saw a major British expedition as a means of returning to office and securing the rebellious Southern colonies for the Crown. They convinced British authorities that such a move would be greeted by a massive uprising of Loyalist sympathizers. The result was a campaign led by Gen. Sir Henry Clinton, who was tasked with opening the Southern front of the war by sailing a 2,500-man expeditionary force on a campaign to take Charleston, South Carolina. Clinton was to secure the colonies, turn over control to the Loyalists, and sail north to join General Howe. When the British expedition reached Cape Fear, North Carolina, Clinton would join forces with Gen. Charles Cornwallis and seven British regiments recently arrived from Europe and then proceed with his mission.

Before the conjoining of Clinton and Cornwallis occurred, events in North Carolina ruined the Crown’s plans. By February 18, more than 1,000 Scottish Highlander Loyalists mustered into service and were soon joined by another 500. Together, they marched from Cross Creek (modern-day Fayetteville) to rally with their British allies at Cape Fear off Wilmington. They were weeks ahead of schedule, and the fleet well behind its timetable. As the Tories moved toward the coast, scouts informed Tory leader Gen. Donald MacDonald that a sizable rebel force intended to fight them before they could join forces with Clinton. MacDonald recommended avoiding a battle, but his zealous younger subordinate commanders argued otherwise.

American Perspective: In the Southern colonies, news of the battles in Massachusetts created a firestorm of activities that firmly divided the colonists into two camps: Tories (British Loyalists) and Patriots (pro-American colonists). Pressure from rebels forced Royal Governor Josiah Martin to flee from the capital. Martin made plans to return to power by combining with British seaborne forces led by Cornwallis and Clinton and reorganizing his fellow Tories into a credible ground force. With the ex-governor no longer in the colony, the Patriots established their own government and raised two regiments and several battalions of militiamen.

In Wilmington, the Patriots organized a defense complete with redoubts to face any approaching enemy. A large Loyalist column made up primarily of Scottish Highlanders was moving in their direction. The North Carolinians organized under the Continental Line at New Bern. Led by Cols. James Moore, Richard Caswell, and Alexander Lillington decided to move into a blocking position to delay, isolate, and perhaps destroy the approaching enemy. They decided to meet them at a bridge spanning the narrow but deep and swift Moores Creek twenty miles outside Wilmington.

For more in-depth research about the Battle of Moore's Creek, read the book Guide to the Battles of the American Revolution written by Theodore Savas and J. David Dameron.

The Fighting: The Loyalist leader decided to assault the Patriots, moving to block his journey to Wilmington, even though neither side seems to have fully appreciated the strength of the other. Loyalist leaders held a council of war the night before the assault. Desertions had whittled their column down to only 800-850 men, but they decided to attack early the next morning. When the old and feeble leader of the small Tory army, General MacDonald, fell ill during the night, command passed to Lt. Col. Donald McLeod.

The Tories broke camp at 1:00 a.m. on February 27 and marched for Moores Creek. Captain John Campbell and 80 men held the advance. The Loyalists, divided into two wings, reach the abandoned Patriot entrenchments and campsite on the near side of the stream. Orders were given to pull back and bring up the wagons and remaining soldiers. The right wing pulled back, but the left wing, under Capt. Alexander McClean continued moving ahead and reached the bridge. As one participant later wrote, “The left wing did not know that the right-wing had marched back.”

At the bridge, McLean and his Loyalists encountered American pickets on the opposite shore, but the darkness prevented him from discovering their true identity. He called them, but no response was forthcoming. Had the rebels withdrawn? The planks had been pulled up from the bridge, indicating that they had. It was at this point that the rebels on the far side of the creek opened fire on the Loyalists, who promptly returned it. The entire Loyalist force surged forward, thinking that attack orders had been given.

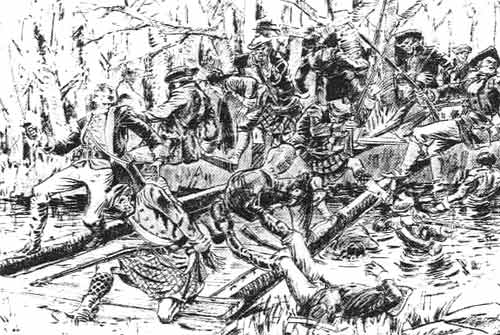

Campbell’s 80 handpicked men, each wielding a Scottish Claymore broadsword, dashed across to secure the bridge. Campbell and McLeod each led a column across the two main bridge stringers. According to some sources, the bridge stringers had been smeared with grease, though the Loyalists would not know this until it was too late.

With Scottish pipes screeching and drums beating, the Loyalists stormed across what was left of the bridge, yelling, “King George and broadswords!” They were unaware that as many as 1,000 rebels were waiting for them behind recently dug entrenchments. At a range of only thirty yards, the rebels opened fire with light artillery and muskets. Protected by mounds of earth, the Patriot fire devastated the small attacking force. The survivors of the initial volley milled about in confusion as they tried to come to grips with the defenders. McLeod, Campbell, and 28 others were mowed down. Many were killed outright. The remainder fell in the few minutes of combat that followed. Some were trampled in the melee; others were shot off or slipped from the greasy stringers and tumbled into the creek, where they drowned or were taken captive.

A brisk rebel counterattack surged over the bridge and pursued the fleeing Loyalists while a rebel flanking move across a nearby ford helped block part of the retreat. A previous order to other North Carolina units to seize Cross Creek led to the capture of hundreds of soldiers. The fight ended decisively. General MacDonald was among the captured.

For more in-depth research about the Battle of Moore's Creek, read the book Guide to the Battles of the American Revolution written by Theodore Savas and J. David Dameron.

Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge: Online Resources

- Wikipedia - Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge

- Journal of the American Revolution - Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge

- DIY Genealogy - Finding your Revolutionary War Ancestor

- National Park Service - Moore's Creek Bridge

- Library of Congress Collection of Revolutionary War Maps

- West Point Battle Maps of the American Revolution

- The History Junkie's Guide to American Revolutionary War Battles

- The History Junkie’s Guide to the American Revolutionary War Timeline

- The History Junkie’s Guide to the 13 Original Colonies