Date: December 9, 1775

Region: Southern Colonies, Chesapeake, Virginia

Commanders: British - John Murray and Captain Samuel Leslie.

American - Colonel William Woodford, Lieutenant Colonel Edward Stevens, and Colonel Robert Howe

British Perspective: As the rebellion gathered strength throughout the colonies, Virginia’s Royal Governor John Murray (Lord Dunmore) fled from the capital at Williamsburg, seeking the safety of the British navy at Norfolk.

An unpopular ruler, Dunmore had two British grenadier companies to provide him protection in Norfolk. He raised an additional two regiments of Loyalists, including the “Royal Ethiopians,” an outfit composed of runaway slaves who served the Crown in return for their freedom.

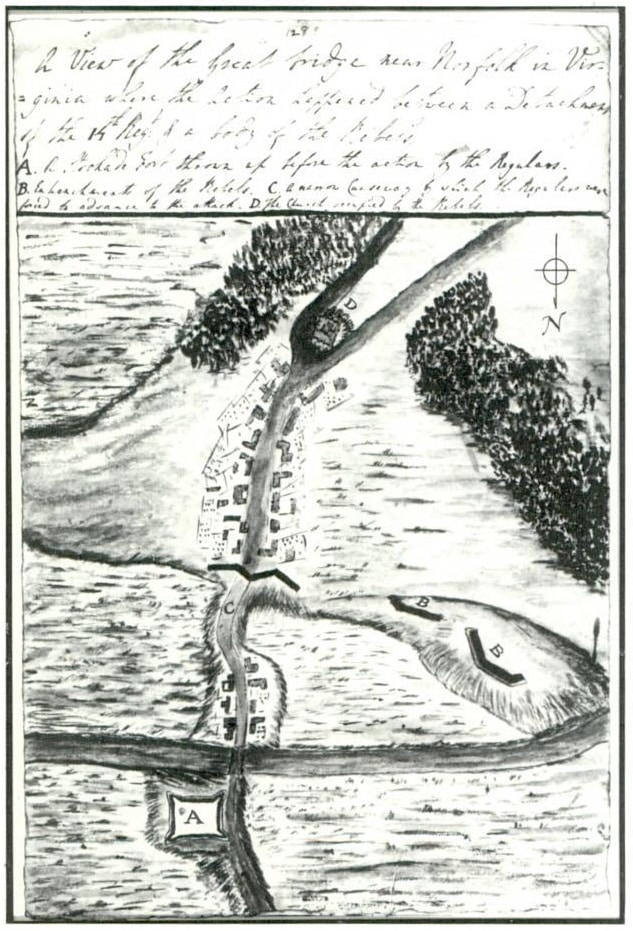

The early war in the New England Colonies was not going well for the British, and it was Dunmore’s hope to crush the rebellion in Virginia and win favor with King George III. Dunmore imposed martial law, erected entrenchments around Norfolk, and constructed Fort Murray, a small log palisade at Great Bridge to control the causeway connecting Norfolk with the Virginia mainland.

This strategic thoroughfare and trade route linked eastern Virginia with North Carolina. His position could not be flanked because of the swampy terrain. Only a headlong attack could dislodge him. In late November, a small force of Patriots arrived to defeat him.

American Perspective: While Lord Dunmore was driven into isolation at Norfolk, his control of the port city and its entrance at Great Bridge depended upon the fort he had constructed there, which posed a threat to the Virginians. While many of the local citizens of Norfolk were sympathetic to the Crown, many more Virginians supported the campaign for independence.

Two Virginia regiments of militia infantry under Col. William Woodford prepared to engage Lord Dunmore and drive him and his soldiers away. Colonel Robert Howe and 150 men from North Carolina joined their neighbors in the quest to defeat Dunmore. Comprised of some 700 militiamen, this composite Patriot force included a young John Marshall, the future Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court, as well as Marshall’s father.

In late November, Colonel Woodford ordered entrenchments built south of the British fort to block the other end of the causeway and isolate and threaten Dunmore’s army. The Virginians expertly threw up parapets within musket range of the fort. Ninety marksmen were left to hold the end of the narrow causeway while the rest camped several hundred yards in the rear. Shots were exchanged over the next few weeks, and a handful of minor skirmishes occurred. Several

The Battle: Dunmore’s outnumbered command was armed with several field pieces and protected by a palisade. The Virginia and North Carolina militiamen had nothing more than small arms and determination. The Virginians had nothing but contempt for Dunmore’s “Fort Murray,” which they referred to as the “Hog Pen.” The fort had been hastily constructed with planks from local houses, logs, and mud and was not a bastion of great strength.

Additionally, the weather was rainy and cold, and the British suffered accordingly in their damp “fortress.” The Americans suffered as well, exposed to the wintry weather that made the standoff a frigid nightmare for everyone involved. Concerned that time favored the Americans (some credit a deserter who lied about Patriot strength), Lord Dunmore decided to attack and drive away from the militia.

An assault was planned for the morning of December 9. Captain Fordyce was ordered to lead a mixed force of 60 grenadiers and another 140 regular infantry, while Captain Samuel Leslie supported the attack with his 230 Royal Ethiopians.

Fordyce’s British grenadiers led the attack before dawn, but it was quickly thrown back in some confusion. The British field pieces were now in position and opened fire on the militia, who were, by this time, all at their posts. Some of the remaining houses between the lines caught fire, and smoke rolled across the American position.

Aligned in rows six men wide, the British infantry stepped off a second time to the beat of their drums, crossed the causeway, and approached the reinforced rebel position with parade-like precision. The bulk of the British slated for the attack, however, waited in reserve near the fort while the grenadiers and light infantry marched on.

There is some evidence that Fordyce believed the light field works had been abandoned because no fire was coming from them. In reality, the Patriot militia had orders to hold their fire until the enemy tramped within point-blank range. Fordyce is said to have yelled, “The day is our own!” as he neared the entrenchments. When the order to fire was given, the colonial militia unleashed several disciplined volleys into the grenadiers.

The British attack faltered as shattered bodies collapsed upon one another. Fordyce fell riddled with musket balls a few yards from the enemy lines. The survivors stumbled back across the causeway in shock.

When the British artillery ceased firing, the American militia counterattacked. Led by Lt. Col. Edward Stevens, the 100 men of the “Culpeper Minutemen” forced the British between the causeway and the fort to fall back into a shrinking enclave, capturing the cannons in the process.

The Virginians fought their enemy “Indian style,” firing individually as they maneuvered closer to the grenadiers. The unconventional tactics worked well against the British, who were unaccustomed and ill-prepared for such unorthodox warfare. The carnage was later accurately described as a slaughter, with the Virginians picking off their trapped and hapless enemy.

Well aware of the disparity of forces available for action, the Virginians retreated to their own defensive works instead of continuing their assault into the strongly held fort. Lord Dunmore sent out a flag of truce to recover the wounded. The day ended as it began, with both sides holding the same positions. That evening, Lord Dunmore ordered his troops to abandon Fort Murray and retreat into Norfolk.

For more in-depth research about the Battle of Great Bridge, read the book Guide to the Battles of the American Revolution written by Theodore Savas and J. David Dameron.

Online Resources

- Wikipedia - Battle of the Great Bridge

- Guide To The Battles of the American Revolution

- Library of Congress Collection of Revolutionary War Maps

- Journal of the American Revolution

- How to Research Your Revolutionary War Ancestor

- The History Junkie’s Guide to the American Revolutionary War

- The History Junkie’s Guide to American Revolutionary War Battles

- The History Junkie’s Guide to the American Revolutionary War Timeline

- The History Junkie’s Guide to the 13 Original Colonies