The Battle of Wilson's Creek was fought ten miles southwest of Springfield, Missouri, on August 10, 1861. Named for the stream that crosses the area where the battle took place, it was a bitter struggle between Union and Southern forces for control of Missouri in the first year of the American Civil War.

Border State Politics

When the Civil War began in 1861, Missouri's allegiance was of vital concern to the federal government. The state's strategic position on the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers and its abundant manpower and natural resources made it imperative that she remain loyal to the Union.

Most Missourians desired neutrality, but many, including the governor, Claiborne Fox Jackson, held strong Southern sympathies and planned to cooperate with the Confederacy in its bid for independence.

When President Abraham Lincoln called for troops to put down the rebellion, Missouri was asked to supply four regiments. Governor Jackson refused the request and ordered State military units to muster at Camp Jackson outside Saint Louis and prepare to seize the U.S. arsenal in that city.

They had not, however, counted on the resourcefulness of the arsenal's commander, Captain Nathaniel Lyon.

Learning of the governor's intentions, Lyon had most of the weapons moved secretly to Illinois. On May 10, he marched 7,000 men out to Camp Jackson and forced its surrender.

In June, after a futile meeting with Governor Jackson to resolve their differences, Lyon - now a brigadier general - led an army up the Missouri River and captured the state capital at Jefferson City.

After an unsuccessful stand at Boonville a few miles upstream, Governor Jackson retreated to southwest Missouri with elements of the State Guard.

Move toward Wilson's Creek

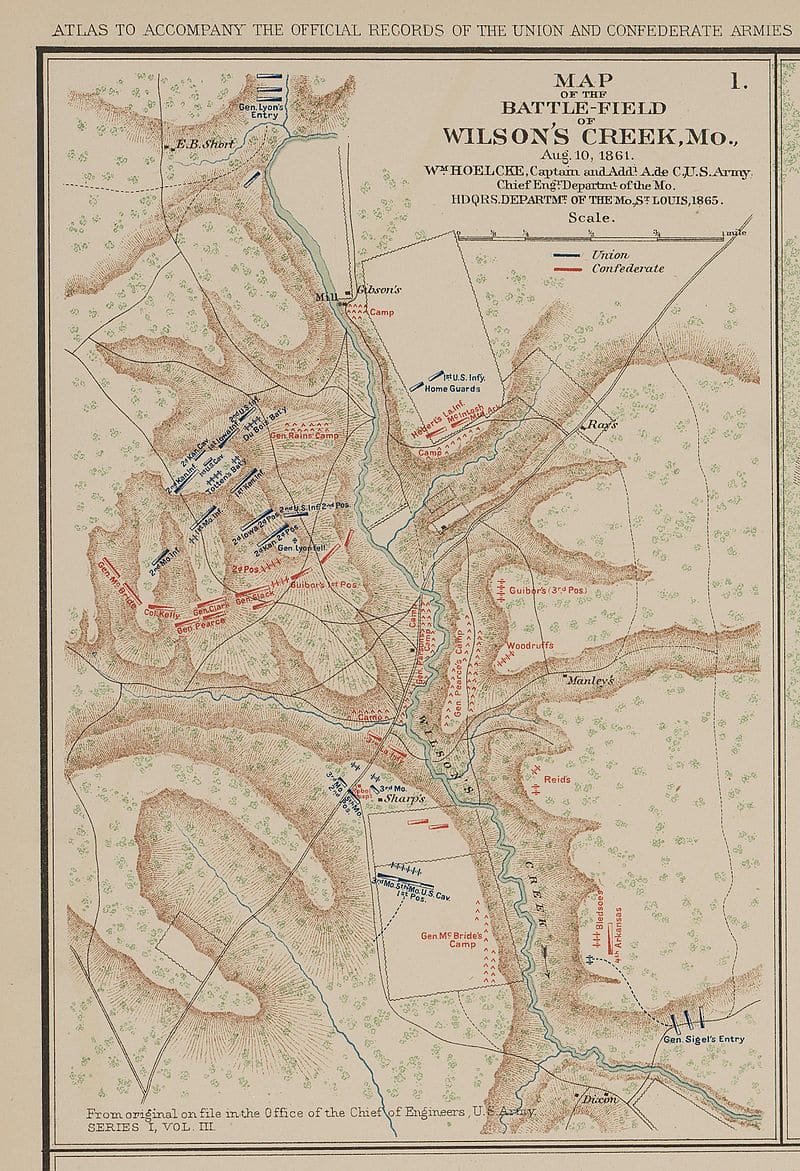

After installing a pro-Union state government and picking up reinforcements, Lyon moved toward southwest Missouri. By July 13, 1861, he was encamped at Springfield with about 6,000 soldiers, consisting of the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 5th Missouri Infantry, the 1st Iowa Infantry, the 1st and 2nd Kansas Infantry, several companies of Regular Army infantry and cavalry, and three batteries of artillery.

Meanwhile, 75 miles southwest of Springfield, Major General Sterling Price, commanding the Missouri State Guard, had been busy drilling the 5,200 soldiers in his charge. By the end of July, when troops under Generals Ben McCulloch and N. Bart Pearce rendezvoused with Price, the total Southern "coalition" force (a mixture of Confederate troops and state forces) exceeded 12,000 men.

On July 31, after formulating plans to capture Lyon's army and regain control of the state, Price, McCulloch, and Pearce marched northeast to attack the Federals.

Lyon, hoping to surprise the Confederates, marched from Springfield on August 1. The next day, the Union troops mauled the Southern vanguard at Dug Springs, but Lyon later discovered he was outnumbered, so he ordered a withdrawal to Springfield. The Confederates followed and, by August 6, were encamped near Wilson's Creek.

The Fighting

Despite inferior numbers, Lyon decided to attack the enemy encampment. Leaving about 1,000 men behind to guard his supplies, the Federal commander led 5,400 soldiers out of Springfield on the night of August 9. Lyon's plan called for 1,200 men under Colonel Franz Sigel to swing wide to the south, flanking the Southern right, while the main body of troops struck from the north. Success hinged on the element of surprise.

Ironically, the Southern leaders also planned a surprise attack on the Federals, but rain on the night of the 9th caused McCulloch (who was now in overall command) to cancel the operation. On the morning of the 10th, Lyon's attack caught the Southerners off guard, driving them back.

Forging rapidly ahead, the Federals occupied the crest of a ridge subsequently called "Bloody Hill." Nearby, the Pulaski Arkansas Battery opened fire, checking the advance.

This gave Price's infantry time to form a battle line on the hill's south slope.

For more than five hours, the battle raged on Bloody Hill. Fighting was often at close quarters, and the tide turned with each charge and countercharge. Sigel's flanking maneuver, initially successful, collapsed altogether when McCulloch's men counterattacked at the Sharp Farm.

Defeated, Sigel and his troops fled.

On Bloody Hill, at about 9:30 a.m., General Lyon, who had been wounded twice already, was positioning his troops when he took a third bullet and became the first general officer killed in the war. Major Samuel Sturgis assumed command of the Federal forces and, by 11 a.m., with ammunition nearly exhausted, ordered a withdrawal to Springfield.

The Battle of Wilson's Creek was over.

Losses were heavy and about equal on both sides: 1,317 for the Federals and 1,222 for the Southerners.

Though victorious on the field, the Southerners were not able to pursue the Union forces. Lyon lost the battle and his life, but he achieved his goal: Missouri remained under Union control.

Conclusion

The Battle of Wilson's Creek marked the beginning of the Civil War in Missouri. For the next three and a half years, the state was the scene of savage and fierce fighting, mostly guerrilla warfare, with small bands of mounted raiders destroying anything military or civilian that could aid the enemy.

By the time the conflict ended in the spring of 1865, Missouri had witnessed so many battles and skirmishes that it ranks as the third most fought-over state in the nation.

The Confederates made only two large-scale attempts to break the Federal hold on Missouri, both of them directed by Sterling Price. Shortly after Wilson's Creek, Price led his Missouri State Guard north and captured the Union garrison at Lexington.

He and his troops remained in the state until early 1862, when a Federal army drove them into Arkansas. The subsequent Union victory at the Battle of Pea Ridge in March kept large numbers of Confederate military forces out of Missouri for more than two years.

In September 1864, Price returned to Missouri with an army of some 12,000 men. By the time his campaign ended, he had marched nearly 1,500 miles, fought 43 battles or skirmishes, and destroyed an estimated $10 million worth of property. Yet the campaign ended in disaster.

At Westport on October 23, Price was soundly defeated in the largest battle fought west of the Mississippi and forced to retreat south. His withdrawal ended organized Confederate military operations in Missouri.