When word of the shootings reached Thomas Hutchinson, eventual Governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony, he quickly ran to King Street and confronted Thomas Preston. Hutchinson reminded Preston that he was not allowed to shoot at any person in public unless a civil magistrate was with him and gave the order.

Hutchinson knew as well as anyone of the civil unrest in Boston. He moved quickly and precisely to diffuse the already escalated situation. He spoke to the Council and told them that he would see justice served on these men, and then he went out to the balcony above the crowd and said, "Let the law have its course. I will live and die by the law."

Jump to:

The crowd, although angry, dispersed. Hutchinson's job was done. Now, it was the law's turn.

The law, just like Hutchinson, moved quickly. Justices John Tudor and Richard Dania called the sheriff in and gave him the warrant to arrest Preston. The Boston Massacre happened in the late evening, and by 3 am, Captain Thomas Preston was arrested and then interrogated.

After the interrogation, he was put into prison, where he and his men stayed for seven months.

As was expected, there was not a lawyer anywhere who would take up a defense for Preston and his men. Most understood that to defend them would mean a loss of business. All would turn their back on justice until, ironically, a young lawyer named John Adams.

John Adams had already emerged as a political force five years before the Boston Massacre when he wrote: "A Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law" in opposition to the Stamp Act of 1765.

He was a well-known patriot and the cousin of Samuel Adams, who was an outspoken voice in opposition of the British officers and the leader of the Sons of Liberty. His decision to represent the British in the Boston Massacre trial was nothing short of risky.

He risked his practice, his fame, his respect, and even, in some sense, his life because he believed it to be necessary that a fair trial is held in New England.

This would prove to King George that the colonies were capable of justice according to the law and not justice by way of a mob.

Trials Begin

It was decided that at the Boston Massacre trial, Preston would be tried separately from his men. This caused a bit of a dilemma since the best defense of Preston was that he did not order the shot, and the best defense of his men was that he did and that they were simply following orders.

Unlike today, John Adams represented both parties and appealed for a joint trial. That motion was denied, and Preston's trial began first.

Adams headed up the defense for Preston, and in the opposing corner, Robert Treat Paine helped prosecute. Paine would eventually become one of the Declaration of Independence signers as well as a representative of Massachusetts Bay in the Continental Congress.

He would help Adams argue for liberty from England, but that would not happen for another 5 years. On this day, he was his competitor.

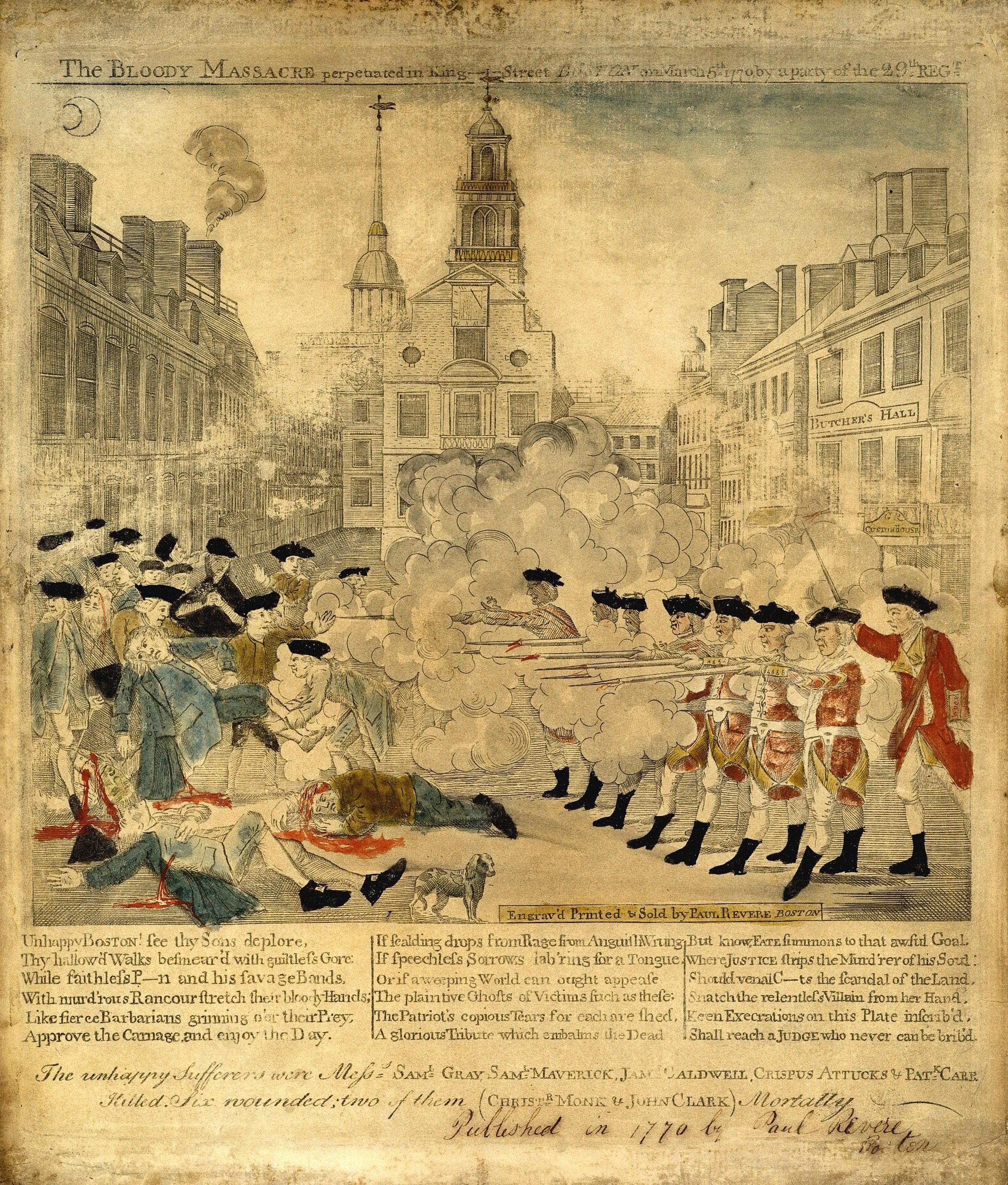

The prosecution's case in the Boston Massacre trial was built on the belief that Preston ordered his men to fire. Preston denied the accusation, and the prosecution would try to negate his claim. Their best witness was Daniel Calef, who was an eyewitness to the Boston Massacre:

I was present at the firing. I heard one of the Guns rattle. I turned about and lookd and heard the officer who stood on the right in line with the Soldiers give the word fire twice. I lookd the Officer in the face when he gave the word and saw his mouth. He had on a red Coat, yellow Jacket, and Silver laced hat with no trimming on his Coat. I saw his face plain. The moon shone on it.

Preston would deny this claim long before the Boston Massacre trial took place:

Some well-behaved persons asked me if the guns were charged. I replied yes. They then asked me if I intended to order the men to fire. I answered no, by no means, observing to them that I was advanced before the muzzles of the men's pieces and must fall a sacrifice if they fired; that the soldiers were upon the half cock and charged bayonets, and my giving the word fire, under those circumstances, would prove me to be no officer. While I was thus speaking, one of the soldiers, having received a severe blow with a stick, stepped a little on one side and instantly fired, on which turning to and asking him why he fired without orders, I was struck with a club on my arm, which for some time deprived me of the use of it, which blow had it been placed on my head, most probably would have destroyed me. On this, a general attack was made on the men by a great number of heavy clubs and snowballs being thrown at them, by which all our lives were in imminent danger, some persons at the same time from behind calling out, damn your bloods-why don't you fire. Instantly, three or four of the soldiers fired, one after another and directly after three more in the same confusion and hurry.

Adams would fight hard and argue extremely well. He was able to create doubt in the minds of the jury. They deliberated and then returned to acquit Preston of all charges.

The second act of the Boston Massacre trial was the trial of Preston's men.

Adams's argument at the Boston Massacre trial was that the men fired in self-defense. He called over 40 witnesses to prove his argument. In the end, he summed it up by saying:

I will enlarge no more on the evidence, but submit it to you.-Facts are stubborn things, and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence: nor is the law less stable than the fact; if an assault was made to endanger their lives, the law is clear, they had a right to kill in their own defence; if it was not so severe as to endanger their lives, yet if they were assaulted at all, struck and abused by blows of any sort, by snow-balls, oyster-shells, cinders, clubs, or sticks of any kind; this was a provocation, for which the law reduces the offence of killing, down to manslaughter, in consideration of those passions in our nature, which cannot be eradicated. To your candour and justice, I submit the prisoners and their cause.

The defense would rest, and the jury sent to deliberate. They would come back and drop all charges of murder on 6 of the 8 men. Hugh Montgomery and Matthew Kilroy would be found guilty of manslaughter and have their thumb branded.

Reactions

The reaction in Boston was mixed, but many were angry. John Adam's practice would suffer, but he would go on to say this about the trial:

The Part I took in Defence of Cptn. Preston and the Soldiers procured me Anxiety and Obloquy enough. It was, however, one of the most gallant, generous, manly, and disinterested Actions of my whole Life and one of the best Pieces of Service I ever rendered to my Country. Judgment of Death against those Soldiers would have been as foul a Stain upon this Country as the Executions of the Quakers or Witches, anciently. As the Evidence was, the Verdict of the Jury was exactly right.