After the Allied attacks on Scimitar Hill and Hill 60 on August 21, 1915, failed to link the Anzac Cove and Suvla Bay sectors, Mediterranean Commander-in-Chief Sir Ian Hamilton sent a telegram to London in a state of growing concern that would eventually begin the Evacuation of Gallipoli in World War 1.

Peninsula Problems

In his telegram, Hamilton requested 95,000 reinforcements from Kitchener, the British war minister. Kitchener only offered 25,000, a quarter of what Hamilton had requested.

Confidence in the Gallipoli operation was dwindling in London and Paris.

Winston Churchill, the former First Lord of the Admiralty and architect of the operation, urged both governments to continue supporting it.

French General Maurice Sarrail suggested a combined offensive against the Asian coast, but his Commander-in-Chief, Joseph Joffre, refused, insisting that France should focus on the Western Front.

Salonika

The invasion of Serbia and plans for a landing at Salonika diverted troops away from Gallipoli, much to the dismay of Hamilton.

The British government offered to provide up to 125,000 troops for the Salonika campaign, even though Kitchener was against it.

Hamilton was already facing criticism from London for the campaign's poor performance. News of the high casualties and lack of progress had reached home, and Australian journalist Keith Murdoch was among those who complained about Hamilton's mismanagement.

Evacuation and Churchill

Hamilton was told on October 11, 1915, that there would be no more reinforcements to the Gallipoli peninsula. He estimated that evacuating the peninsula would result in up to 50% casualties, which was considered too high.

This led to his removal as Commander-in-Chief and recall to London on October 14.

Sir Charles Monro replaced Hamilton. He arrived on the peninsula on October 28 and immediately recommended evacuating the peninsula.

Kitchener did not agree, so Monro traveled to the region to see the situation for himself.

Upon arrival, Monro saw the poor conditions facing the Allied forces and recommended evacuating the peninsula on November 15.

He overruled arguments by senior naval figures Sir Roger Keyes and Rosslyn Wemyss to attempt a naval seizure again.

The British government finally agreed to evacuate the peninsula on December 7. However, a heavy blizzard had set in, making the operation hazardous.

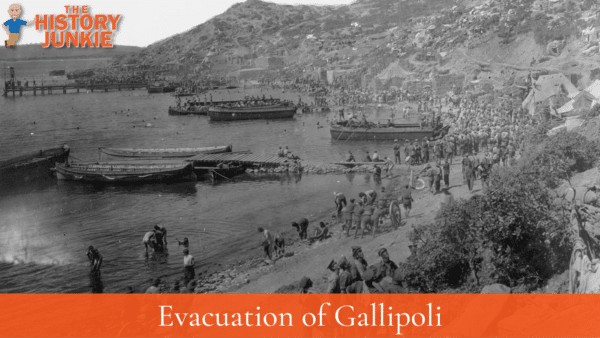

Nevertheless, the evacuation of 105,000 men and 300 guns from Anzac Cove and Suvla Bay was successfully conducted from December 10-20.

The evacuation of Helles, comprising 35,000 men, was conducted from late December until January 9, 1916.

The evacuation operation was the most successful element of the entire campaign, with casualty figures significantly lower than Hamilton had predicted.

Painstaking efforts had been made to deceive the 100,000 Turkish troops into believing that the movement of Allied forces did not constitute a withdrawal.

Winston Churchill, however, was critical of Monro's achievement, writing that he "came, he saw, he capitulated."

This criticism has persisted over the years, overshadowing Monro's correct decision and remarkable follow-through.