J. P. Morgan was an American financier, banker, philanthropist, and art collector who dominated corporate finance and industrial consolidation during the Gilded Age. In 1892, Morgan arranged the merger of Edison General Electric and Thompson-Houson Electric Company to form General Electric.

After financing the creation of the Federal Steel Company, he merged the Carnegie Steel Company and several other steel and iron businesses to form the United States Steel Corporation in 1901. He played a key role in ending the Panic of 1907.

A leading art collector, he bequeathed much of his large collection to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. At the height of Morgan's career during the early 1900s, he and his partners had financial investments in many large corporations and were accused by critics of controlling the nation's high finance. By 1901, he was one of the wealthiest men in the world.

Early Life

J.P. Morgan was born in Hartford, Connecticut, to Junius Spencer Morgan (1813 - 1890) and Juliet Pierpont (1816 - 1884) of Boston, Massachusetts. Pierpont, as he preferred to be known, had a varied education due in part to interference by his father, Junius. In the autumn of 1848, Pierpont transferred to the Hartford Public School and then to the Episcopal Academy in Cheshire, boarding with the principal.

In September 1851, Morgan passed the entrance exam for the English High School of Boston, a school specializing in Mathematics to prepare young men for careers in commerce.

In the spring of 1852, an illness that was to become more common as his life progressed struck; rheumatic fever left him in so much pain that he couldn't walk. Junius sent the boy to the Azores in order for him to recover.

After convalescing for almost a year, Pierpont returned to the school in Boston to resume his studies. After graduating, he attended Bellerive, a school near the Swiss village of Vevey. When Morgan had attained fluency in French, he attended the University of Göttingen in order to improve his German.

Early Career

Morgan entered banking in his father's London branch in 1856, moving to New York City the next year, where he worked at the banking house of Duncan, Sherman & Company, the American representatives of George Peabody & Company. From 1860 to 1864 (During most of the Civil War), as J. Pierpont Morgan & Company, he acted as an agent in New York for his father's firm. By 1864-71, he was a member of the firm of Dabney, Morgan & Company; in 1871, he partnered with the Drexels of Philadelphia to form the New York firm of Drexel, Morgan & Company.

In 1895, it became J. P. Morgan & Company and retained close ties with Drexel & Company of Philadelphia, Morgan, Harjes & Company of Paris, and J. S. Morgan & Company (after 1910, Morgan, Grenfell & Company) of London. By 1900, it was one of the most powerful banking houses in the world, carrying through many deals, especially reorganizations and consolidations. Morgan had many partners over the years, such as George W. Perkins, but remained in firm charge.

Morgan's ascent to power was accompanied by dramatic financial battles. He wrested control of the Albany and Susquehanna Railroad from Jay Gould and Jim Fisk in 1869. He led the syndicate that broke the government-financing privileges of Jay Cooke and soon became deeply involved in developing and financing a railroad empire by reorganizations and consolidations in all parts of the United States. He raised large sums in Europe, but instead of only handling the funds, he helped the railroads reorganize and achieve greater efficiencies.

He fought against the speculators interested in speculative profits and built a vision of an integrated transportation system. In 1885, he reorganized the New York, West Shore & Buffalo Railroad, leasing it to the New York Central. In 1886, he reorganized the Philadelphia & Reading, and in 1888 the Chesapeake & Ohio.

After Congress passed the Interstate Commerce Act in 1887, Morgan set up conferences in 1889 and 1890 that brought together railroad presidents in order to help the industry follow the new laws and write agreements for the maintenance of "public, reasonable, uniform and stable rates" The conferences were the first of their kind, and by creating a community of interest among competing lines paved the way for the great consolidations of the early 20th century.

Morgan's process of taking over troubled businesses to reorganize them was known as "Morganization." Morgan reorganized business structures and management in order to return them to profitability. Morgan's reputation as a banker and financier also helped bring interest from investors to the businesses he took over.

In 1895, at the depths of the Panic of 1893, the Federal Treasury was nearly out of gold. President Grover Cleveland arranged for Morgan to create a private syndicate on Wall Street to supply the U.S. Treasury with $65 million in gold, half of it from Europe, to float a bond issue that restored the treasury surplus of $100 million.

The episode saved the Treasury but hurt Cleveland with the agrarian wing of his Democratic party and became an issue in the election of 1896 when banks came under withering attack from William Jennings Bryan. Morgan and Wall Street bankers donated heavily to Republican William McKinley, who was elected in 1896 and reelected in 1900 on a gold standard platform.

In 1902, J. P. Morgan & Co. purchased the Leyland line of Atlantic steamships and other British lines, creating an Atlantic shipping combine, the International Mercantile Marine Company, which eventually became the owner of White Star Line, builder and operator of RMS Titanic. In addition, J P Morgan & Co (or the banking houses to which it succeeded) reorganized a large number of railroads between 1869 and 1899.

Later Career

After the death of his father in 1890, Morgan took control of J. S. Morgan & Co. (re-named Morgan, Grenfell & Company in 1910). Morgan began talks with Charles M. Schwab, president of Carnegie Co., and businessman Andrew Carnegie in 1900 with the intention of buying Carnegie's business and several other steel and iron businesses to consolidate them to create the United States Steel Corporation. Carnegie agreed to sell the business to Morgan for $480 million.

The deal was closed without lawyers and without a written contract. News of the industrial consolidation arrived in newspapers in mid-January 1901. U.S. Steel was founded later that year and was the first billion-dollar company in the world with an authorized capitalization of $1.4 billion. History of U. S. Steel. United States Steel. Retrieved on 24 October 2013.

U.S. Steel aimed to achieve greater economies of scale, reduce transportation and resource costs, expand product lines, and improve distribution. It was also planned to allow the United States to compete globally with the United Kingdom and Germany. U.S. Steel's size was claimed by Schwab and others to allow the company to pursue distant international markets-globalization.

U.S. Steel was regarded as a monopoly by critics, as the business was attempting to dominate not only steel but also the construction of bridges, ships, railroad cars and rails, wire, nails, and a host of other products.

With U.S. Steel, Morgan had captured two-thirds of the steel market, and Schwab was confident that the company would soon hold a 75 percent market share. However, since 1901, the businesses' market share dropped, never reaching Schwab's dream of seventy-five percent market share.

Morgan also financed manufacturing and mining businesses and controlled banks, insurance companies, shipping lines, and communications systems. Through his firm came enormous funds from abroad to help develop American resources.

Enemies of banking attacked Morgan for the terms of his loan of gold to the federal government in the 1895 crisis, for his financial resolution of the Panic of 1907, and for bringing on the financial ills of the New York, New Haven & Hartford RR.

In 1912, the Pujo Committee, a subcommittee of the House Banking and Currency Committee, found that the partners of J.P. Morgan & Co., along with the directors of First National and National City Bank, controlled aggregate resources of $22,245,000,000. Louis Brandeis, the former U.S. Supreme Court Justice, compared this sum to the value of all the property in the twenty-two states west of the Mississippi River.

In 1900, Morgan financed inventor Nikola Tesla and his Wardenclyffe Tower with $150,000 for experiments in radio. Tesla was unsuccessful, and in 1904, Morgan pulled out. At the height of Morgan's career during the early 1900s, he and his partners controlled directly and indirectly assets worth $1.3 billion

Family and Death

Morgan was a lifelong member of the Protestant Episcopal Church and, by 1890, was one of its most influential leaders.

In 1861, he married Amelia Sturges (1835–1862). After her death the next year, he married Frances Louise Tracy (1842–1924) on May 3, 1863, and they had the following children:

- Louisa Pierpont Morgan (1866–1946), who married Herbert Livingston Satterlee (1863–1947),

- Jack Pierpont Morgan (1867–1943),

- Juliet Morgan (1870–1952), and

- Anne Morgan (1873–1952).

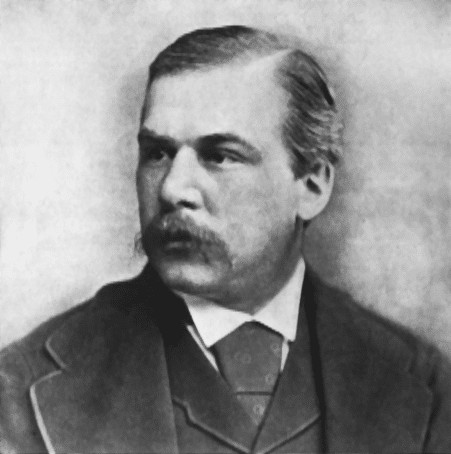

Morgan was physically large with massive shoulders, piercing eyes, and a purple nose because of a childhood skin disease, rosacea. His grotesquely deformed nose was due to a disease called rhinophyma, which is the end result of acne rosacea. As the deformity worsens, pits, nodules, fissures, lobulations, and pedunculation contort the nose into grotesque cosmetic problems.

This condition inspired the taunt: "Johny Morgan's nasal organ has a purple hue." Surgeons could have shaved away the rhinophymous growth of sebaceous tissue during Morgan's lifetime, but as a child, Morgan suffered from infantile seizures, and it is suspected that he did not seek surgery for his nose because he feared the seizures would return.

His social and professional self-confidence were well too established to be undermined by this affliction. It appeared as if he dared people to meet him squarely and not shrink from the sight, asserting the force of his character over the ugliness of his face.

He was known to dislike publicity and hated being photographed; as a result of his self-consciousness of his rosacea, all of his professional portraits were retouched. He smoked large Havana cigars called Hercules' Clubs and often had a tremendous physical effect on people; one man said that a visit from Morgan left him feeling "as if a gale had blown through the house."

Morgan died while traveling abroad in Rome. At the time of his death, he had an estate worth $80 million (approximately $1.2 billion today). His remains were interred in the Cedar Hill Cemetery in his birthplace of Hartford.

His son, J. P. Morgan, Jr., inherited the banking business.