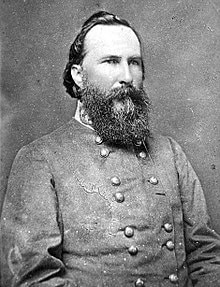

James Longstreet was called "The Old Warhorse" by Robert E. Lee and was one of the foremost generals of the Confederate Army. He famously resisted the infamous Pickett's Charge and could only muster a head nod when he gave the order to commence the charge and was known for riding too close to the line during a battle. He was well-respected by both Union and Confederate officers and had exceptional service during the Mexican-American War. After the war, he had a successful career as a diplomat and converted to the Republican Party.

Jump to:

Early Life

James Longstreet was born on January 8, 1821, in Edgefield District, South Carolina, an area that is now part of North Augusta, Edgefield County. He was the fifth child and third son of James Longstreet (1783-1833), of Dutch descent, and Mary Ann Dent (1793-1855), of English descent, originally from New Jersey and Maryland, respectively, who owned a cotton plantation close to where the village of Gainesville would be founded in northeastern Georgia. James's ancestor, Dirck Stoffels Langestraet, immigrated to the Dutch colony of New Netherland in 1657, but the name became Anglicized over the generations. James's father was impressed by his son's "rocklike" character on the rural plantation, giving him the nickname Peter, and he was known as Pete or Old Pete for the rest of his life.

Longstreet's father decided on a military career for his son but felt that the local education available to him would not be adequate preparation. At the age of nine, James was sent to live with his aunt and uncle in Augusta, Georgia. His uncle, Augustus Baldwin Longstreet, was a newspaper editor, educator, and Methodist minister. James spent eight years on his uncle's plantation, Westover, just outside the city, while he attended the Academy of Richmond County. His father died from a cholera epidemic while visiting Augusta in 1833; although James's mother and the rest of the family moved to Somerville, Alabama, following his father's death, James remained with Uncle Augustus. Augustus Longstreet, a man of some political prominence, was a fierce states' rights partisan who supported South Carolina during the Nullification Crisis.

Mexican-American War

Longstreet served with distinction in the Mexican–American War with the 8th U.S. Infantry. He fought under Zachary Taylor as a lieutenant in May 1846 in the battles of Palo Alto and the Battle of Resaca de la Palma while saying nothing in his memoirs about his personal role in the battles. He fought again with Taylor's army at the Battle of Monterrey in September 1846. He received brevet promotions to captain for Contreras and Churubusco and to major for Molino del Rey. In the Battle of Chapultepec on September 12, 1847, he was wounded in the thigh while charging up the hill with his regimental colors; falling, he handed the flag to his friend, Lt. George E. Pickett, who was able to reach the summit.

After the war and his recovery from the Chapultepec wound, Longstreet and Louise Garland were officially married on March 8, 1848, and the marriage produced 10 children. He and his new wife served on frontier duty in Texas, primarily at Fort Martin Scott near Fredericksburg and Fort Bliss in El Paso. He performed scouting missions and also served as major and paymaster for the 8th Infantry from July 1858. Author Kevin Phillips claims that during this period, Longstreet was involved in a plot to draw the Mexican state of Chihuahua into the Union as a slave state.

Civil War

Longstreet was not enthusiastic about secession from the Union, but he had long been infused with the concept of states' rights and felt he could not go against his homeland. Although he was born in South Carolina and reared in Georgia, he offered his services to the state of Alabama, which had appointed him to West Point, where his mother still lived. Furthermore, he was the senior West Point graduate from that state, which implied a commensurate rank in the state's forces would be available. After settling his accounts, he resigned from the U.S. Army on May 8, 1861, to cast his lot with the Confederacy in the Civil War.

Longstreet arrived in Richmond, Virginia, with a commission as a lieutenant colonel in the Confederate States Army. He met with Confederate President Jefferson Davis at the executive mansion on June 22, 1861, where he was informed that he had been appointed a brigadier general with a date of rank on June 17, a commission he accepted on June 25. He was ordered to report to Brig. Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard at Manassas, where he was given command of a brigade of three Virginia regiments—the 1st, 11th, and 17th Virginia Infantry regiments in the Confederate Army of the Potomac.

Longstreet assembled his staff and trained his brigade constantly. They saw their first action at Blackburn's Ford on July 18, resisting a Union Army reconnaissance force that preceded the First Battle of Bull Run. When the main attack came at the opposite end of the line on July 21, the brigade played a relatively minor role, although it endured artillery fire for nine hours. Between 5 and 6 in the evening, Longstreet received an order from Johnston instructing him to take part in the pursuit of the Federal troops, who had been defeated and were fleeing the battlefield. He obeyed, but when he met the brigade of Brigadier General Milledge Bonham, Bonham, who outranked Longstreet, ordered him to retreat. An order soon arrived from Johnston ordering the same. Longstreet was infuriated that his commanders would not allow a vigorous pursuit of the defeated Union Army. His trusted Chief of Staff, Moxley Sorrel, recorded that he was "in a fine rage. He dashed his hat furiously to the ground, stamped, and bitter words escaped him." He quoted Longstreet as saying afterward, "Retreat! Hell, the Federal army has broken to pieces."

On October 7, Longstreet was promoted to major general and assumed command of a division in the newly reorganized and renamed Confederate Army of Northern Virginia with four infantry brigades-commanded by generals Daniel Harvey Hill, David R. Jones, Bonham, and Louis Wigfall-as well as Hampton's Legion, which was under Wade Hampton III.

Tragedy struck the Longstreet family in January 1862. A scarlet fever epidemic in Richmond, Virginia, claimed the lives of his one-year-old daughter Mary Anne, his four-year-old son James, and eleven-year-old Augustus ("Gus"), all within a week. His 13-year-old son Garland almost succumbed. The losses were devastating for Longstreet, and he became withdrawn, both personally and socially. In 1861, his headquarters were noted for parties, drinking, and poker games. After he returned from the funeral, the headquarters of social life became, for a time, more somber. He rarely drank, and his religious devotion increased.

Civil War Service

Longstreet participated in many battles throughout the war. He had his hand in most of the engagements that happened in Virginia and the Eastern Theatre. Here are some of the highlights:

- First Battle of Bull Run - Participated and only played a role in the Yankee's retreat.

- Peninsula Campaign - Served well as a rear guard defeating Thomas Hooker and forcing his line to retreat.

- Battle of Seven Pines - he marched his men in the wrong direction down the wrong road, causing congestion and confusion with other Confederate units, diluting the effect of the massive Confederate counterattack against McClellan.

- Second Bull Run: He executed a strong defensive and strategic offensive tactic under the orders of General Lee. The Confederates defeated the Union.

- Battle of Antietam - Once again, executed a strong defense against a stronger force. After the delaying action Longstreet's corps fought at South Mountain, he retired to Sharpsburg to join Stonewall Jackson and prepared to fight a defensive battle. Using terrain to his advantage, Longstreet validated his idea that the tactical defense was now vastly superior to the exposed offense. He was one of the first Generals in the Civil War to recognize that previous tactics were not as effective against the advanced technology.

- Battle of Fredericksburg - Fredericksburg was a defensive masterpiece set in place by Longstreet. He arrived early and dug trenches, built up a stone wall, strategically placed artillery, and created a kill zone. The Union lost 8,000 men while Longstreet only 1,000.

- Siege of Suffolk - In April, Longstreet besieged Union forces in the city of Suffolk, Virginia, a minor operation but one that was very important to Lee's army, still stationed in war-devastated central Virginia. It enabled Confederate authorities to collect huge amounts of provisions that had been under Union control. However, this operation caused Longstreet and 15,000 men of the First Corps to be absent from the Battle of Chancellorsville in May.

- Battle of Gettysburg - Longstreet was opposed to any action at Gettysburg. He advised Lee to divide his forces and drive towards the Ohio River in order to force General Grant to break his hold on Vicksburg. Lee did not agree and moved forward with Gettysburg. During the battle, Longstreet advised against Pickett's charge and was again overrode by General Lee. When the time came to order the attack, Longstreet could only nod and watch his men get obliterated by well-entrenched Union infantry and artillery.

- Battle of Chickamauga - Longstreet arrived and was placed in command of the Left Wing of General Braxton Bragg's army. Chickamauga became a signature victory for Longstreet when he successfully smashed the Union army and sent them into a frantic retreat. Chickamauga was the greatest Confederate victory in the Western Theater, and Longstreet deserved and received a good portion of the credit.

- Battle of Campbell's Station - Union successfully evaded Longstreet's army

- Battle of Fort Sanders - Failed to break through Union lines in Tennessee

- Battle of The Wilderness: -Saved Confederacy from defeat with an exceptional flanking maneuver. Put into play advanced tactics. He was wounded by his own men and treated in Lynchburg, Virginia.

- Appomattox - Longstreet believed that General Grant would give fair terms. Grant did, and Lee surrendered.

Post-War Life

After the war, General James Longstreet retired to New Orleans, where he pursued multiple business ventures. He, along with some other Confederate commanders, put their political support behind the dominant Republican party during Reconstruction. This caused much of his legacy in the South to be distorted as he was viewed as disloyal for switching parties after fighting for the Confederacy.

In 1875, the Longstreet family left New Orleans with concerns over health and safety, returning to Gainesville, Georgia. By this time, Louise had given birth to ten children, five of whom lived to adulthood. He applied for various jobs through the Rutherford B. Hayes administration and was briefly considered for Secretary of the Navy. He served briefly as deputy collector of internal revenue and as postmaster of Gainesville. In 1880, President Hayes appointed Longstreet as his ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, and later, he served from 1897 to 1904 under Presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt as U.S. Commissioner of Railroads, succeeding Wade Hampton III.

On one of his frequent return trips to New Orleans on business, Longstreet converted to Catholicism in 1877 and was a devout believer until his death. He served as a U.S. Marshal from 1881 to 1884, but the return of a Democratic administration under Grover Cleveland ended his political career, and he went into semiretirement on a 65-acre farm near Gainesville, where he raised turkeys and planted orchards and vineyards on the terraced ground that his neighbors referred to jokingly as "Gettysburg." A devastating fire on April 9, 1889, destroyed his house and many of his personal possessions, including his personal Civil War documents and memorabilia. That December, Louise Longstreet died. In 1897, at the age of 76, in a ceremony at the governor's mansion in Atlanta, he married 34-year-old Helen Dortch. Although Longstreet's children reacted poorly to the marriage, Helen became a devoted wife and avid supporter of his legacy after his death. She outlived him by 58 years, dying in 1962.

After Louise's death, and after bearing criticism of his war record from other Confederates for decades, Longstreet refuted most of their arguments in his memoirs entitled From Manassas to Appomattox, a labor of five years that was published in 1896. His final years were marked by poor health and partial deafness. In 1902, he suffered from severe rheumatism and was unable to stand for more than a few minutes at a time. His weight diminished from 200 to 135 pounds by January 1903. Cancer developed in his right eye, and in December, he had X-ray therapy in Chicago to treat it. He contracted pneumonia and died in Gainesville on January 2, 1904, six days before his 83rd birthday. Longstreet's remains are buried in Alta Vista Cemetery. He outlived most of his detractors and was one of only a few general officers from the Civil War to live into the 20th century.

General James Longstreet: Online Resources

- Wikipedia - James Longstreet

- Longstreet Museum

- The Longstreet Society

- The Forgotten Confederate General

- Find a Grave - General Longstreet

- The History Junkie's Complete Guide to the Civil War

- The History Junkie's Civil War Timeline

- General James Longstreet: The Confederacy's Most Controversial Soldier

- General James Longstreet at Gettysburg: Longstreet's Account of the Battle from His Memoirs, From Manassas to Appomattox