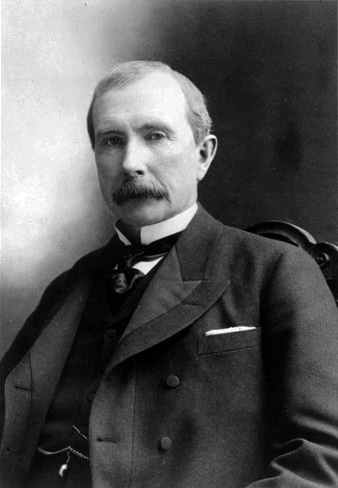

John D. Rockefeller (John Davison Rockefeller, Sr.) (1839 – 1937) was a leading American industrialist, financier, philanthropist, and founder of a powerful family of bankers and politicians. He revolutionized the oil industry and defined the structure of modern philanthropy during the Gilded Age.

He was one of the two or three most prominent businessmen and philanthropists of the Progressive Era and captured its spirit of efficiency. From childhood, Rockefeller strongly believed that his purpose in life was to make as much money as possible and then use it wisely to improve the lot of mankind. In 1862, Rockefeller founded the Standard Oil Company and ran it until he retired in the late 1890s.

He kept his stock, and as gasoline grew in importance, his wealth soared, and he became the world's richest man and first billionaire.

He was the target of multiple attacks before and after Standard Oil was convicted in federal court of criminal monopolistic practices and broken up in 1911. Rockefeller spent the last forty years of his life creating the modern systematic approach of targeted philanthropy, creating foundations that had a major impact on medicine, education, and scientific research.

His foundations pioneered the development of medical research and was instrumental in the eradication of hookworm and yellow fever.

He was a devout Northern Baptist and supported many church-based institutions throughout his life, most notably the University of Chicago.

Early Life

John was born in Richford, New York, the son of William Avery Rockefeller and Eliza (Davison) Rockefeller. His father, a traveling salesman of dubious medical cures, was supporting a bigamous second family and was seldom home.

John was of Scots, Yankee, and German ancestry. His mother was a devoutly religious Baptist, strait-laced and austere. John was the second of six children and the oldest of three sons. The family moved around a great deal, and he attended public schools haphazardly in several towns until he received a good education in Owego, New York, and then attended the excellent Cleveland High School in 1853–55; he now studied hard and did well in mathematics. He never attended college, but three months at a local business school gave him the basics of bookkeeping and commercial and banking practice.

Early Career

His first job, starting at $3.50 a week, was clerking for commission merchants who had a diversified business with railroads, steamship lines, producers, and merchants. Three years later, the young man was well-known and trusted in the Cleveland business community. He formed a partnership with a young Englishman, Maurice B. Clark, for handling grain, hay, meats, and other goods.

On a combined capital of only $4,000, they had sales of the first year, 1859–60, of $450,000 and made a profit of $4,400. Clark & Rockefeller boomed during the Civil War, shipping the army many products of the city and region.

Deeply religious, John D. Rockefeller not only joined the Erie Street Baptist Church in 1854 but soon became its leading lay figure. He helped with the maintenance of the building, served as a recording clerk, taught Sunday School, and became one of the five trustees.

Starting with his first pay packet, he always gave to charities about 10% of what he received. He was opposed to slavery and helped a former slave from Cincinnati buy his slave wife. By 1860, he was head of the family as his father was largely gone. His family responsibilities and his business role in supplying the army precluded him from volunteering for the army.

In 1865, he married Laura Celestia Spelman, daughter of a Cleveland, Ohio businessman of Yankee origins.

Journey Into Oil

Rockefeller's entrepreneurial interests turned to the frenzied development of the "Oil Regions" in northwestern Pennsylvania. Oil was used to make kerosene for lighting; it was much superior and cheaper than candles. The industry grew explosively, with wells being drilled, refineries opened, an export market created, and the opening of the Atlantic & Great Western Railroad linking Cleveland to the oil fields. Many small refineries were built in Cleveland.

Boom and bust was the story of oil, as too many wells were drilled and too many refineries opened. Rockefeller realized that Cleveland's closeness to the oil fields and its superb transportation system by rail and steamboats on the Great Lakes gave it a competitive advantage over other cities.

In 1863, he, three Clark brothers, and chemist Samuel Andrews, an expert in refining methods, built the Excelsior refinery. In February 1865, he paid $72,500 to buy out the Clarks and partner only with Andrews. That marked his full-time entry into the oil business and, he wrote later, "was the day that determined my career."

By November, his refinery was the largest of the 30 in Cleveland. Its sales in 1865 reached $1,200,000; its capacity of 500 barrels a day was double that of the nearest competitor. Rockefeller built a second refinery, the Standard Works, and send his brother William, now a partner too, to New York to organize the export and eastern trade.

The leading Cleveland bankers funded the firm. "I was always a great borrower in those days," he recalled. Unlike most oilmen, he was methodical, systematic, and thorough in his planning, avoiding the speculation, waste, and guesswork that characterized most of his get-rich-quick competitors. Oil prices were high in 1865-66, and now there were fifty rival refineries in Cleveland and 80 in Pittsburgh.

Overproduction resulted, ending prices down in 1867–68. Bankruptcy engulfed both well-owners and small refineries that had over-expanded on borrowed money they could not repay. The strength, efficiency, and foresight of the Rockefeller firm kept it profitable.

Predeceased by his wife, Laura Spelman Rockefeller, the Rockefellers had four daughters and one son (John D. Rockefeller, Jr.). "Junior" was largely entrusted with the supervision of the foundations.

Standard Oil

Having outgrown the partnership form of organization, Rockefeller incorporated Standard Oil Company of Ohio in early 1870 with 10,000 shares of $100 par value, of which Rockefeller held 2,667.

Cleveland was one of the main refining centers in the U.S., and Standard was the most profitable refiner in Cleveland. When it was found out that at least part of Standard Oil's cost advantage came from secret rebates from the railroads bringing oil into Cleveland, the competing refiners insisted on getting similar rebates, and the railroads quickly complied. By then, however, Standard Oil had grown to become one of the largest shippers of oil and kerosene in the country.

The railroads were competing fiercely for traffic and, in an attempt to create a cartel to 'stabilize' freight rates, formed the South Improvement Company. Rockefeller agreed to support this cartel if they gave him preferential treatment as a high-volume shipper, which included not just steep rebates for his product but also rebates for the shipment of competing products. Part of this scheme was the announcement of sharply increased freight charges.

This touched off a firestorm of protest, which eventually led to the discovery of Standard Oil's part of the deal. A major New York refiner, Charles Pratt and Company, headed by Charles Pratt and Henry H. Rogers, led the opposition to this plan, and railroads soon backed off.

Undeterred, Rockefeller continued with his self-reinforcing cycle of buying competing refiners, improving the efficiency of his operations, pressing for discounts on oil shipments, undercutting his competition, and buying them out. In six weeks in 1872, Standard Oil had absorbed 22 of its 26 Cleveland competitors.

Eventually, even his former antagonists, Pratt and Rogers, saw the futility of continuing to compete against Standard Oil, and in 1874, they made a secret agreement with their old nemesis to be acquired. Pratt and Rogers became Rockefeller's partners. Rogers, in particular, became one of Rockefeller's key men in the formation of the Standard Oil Trust. Pratt's son, Charles Millard Pratt, became Secretary of Standard Oil.

For many of his competitors, Rockefeller had merely to show them his books so they could see what they were up against and then make them a decent offer. If they refused his offer, he told them he would run them into bankruptcy, then cheaply buy up their assets at auction.

Most capitulated.

Becoming a Monopoly

Standard Oil gradually gained almost complete control of all oil production in America. At that time, many legislatures had made it difficult to incorporate in one state and operate in another. As a result, Rockefeller and his partners owned separate companies across dozens of states, making their management of the whole enterprise rather unwieldy. In 1882, Rockefeller's lawyers created an innovative form of partnership to centralize their holdings, giving birth to the "Standard Oil Trust."

The partnership's size and wealth drew much attention. Despite improving the quality and availability of kerosene products while greatly reducing their cost to the public (the price of kerosene dropped by nearly 80% over the life of the company), Standard Oil's business practices created intense controversy.

The firm was attacked by journalists and politicians throughout its existence for its monopolistic practices, giving momentum to the anti-trust movement.

One of the most effective attacks on Rockefeller and his firm was the 1904 publication of The History of the Standard Oil Company by Ida Tarbell. Tarbell was a leading muckraker. Although her work prompted a huge backlash against the company, Tarbell claims to have been surprised at its magnitude.

“I never had an animus against their size and wealth, never objected to their corporate form. I was willing that they should combine and grow as big and wealthy as they could, but only by legitimate means. But they had never played fair, and that ruined their greatness for me.” (Tarbell's father had been driven out of the oil business during the South Improvement Company affair.)

Ohio was especially vigorous in applying its state anti-trust laws and finally forced a separation of Standard Oil of Ohio from the rest of the company in 1892, leading to the dissolution of the trust. Rockefeller continued to consolidate his oil interests as best as he could until New Jersey, in 1899, changed its incorporation laws to effectively allow a re-creation of the trust in the form of a single holding company.

At its peak, Standard Oil had about 90% of the market for kerosene products.

By 1896, Rockefeller shed all of his policy involvement in the affairs of Standard Oil; however, he retained his nominal title as president until 1911; when he kept his stock.

In 1911, the Supreme Court of the United States held that Standard Oil, which by then still had a 64% market share, originated in illegal monopoly practices and ordered it to be broken up into 34 new companies.

These included, among many others, Continental Oil, which became Conoco; Standard of Indiana, which became Amoco; Standard of California, which became Chevron; Standard of New Jersey, which became Exxon; Standard of New York, which became Mobil; and Standard of Ohio, which became Sohio. John D. Rockefeller, who had rarely sold shares, owned stock in all of them.

Giving Back

From his very first paycheck, John D. Rockefeller tithed ten percent of his earnings to his church. As his wealth grew, so did his giving, primarily to educational and public health causes but also to basic science and the arts. He was advised primarily by Frederick T. Gates after 1891 and, after 1897, also by his son.

Rockefeller believed in the Efficiency Movement, arguing that

"To help an inefficient, ill-located, unnecessary school is a waste...it is highly probable that enough money has been squandered on unwise educational projects to have built up a national system of higher education adequate to our needs if the money had been properly directed to that end."

He and his advisors invented the conditional grant that required the recipient to "root the institution in the affections of as many people as possible who, as contributors, become personally concerned, and thereafter may be counted on to give to the institution their watchful interest and coöperation."

In 1884, he provided major funding for a college in Atlanta for black women that became Spelman College (named for Rockefeller's in-laws who were ardent abolitionists before the Civil War). Rockefeller also gave considerable donations to Denison University and other Baptist colleges.

Rockefeller gave $80 million to the University of Chicago under William Rainey Harper, turning a small Baptist college into a world-class institution by 1900. He later called it "the best investment I ever made."

His General Education Board, founded in 1902, was established to promote education at all levels everywhere in the country. It was especially active in supporting black schools in the South. Its most dramatic impact came by funding the recommendations of the Flexner Report of 1910, which revolutionized the study of medicine in the United States.

Despite his personal preference for homeopathy, Rockefeller, on Gates's advice, became one of the first great benefactors of medical science. In 1901, he founded the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in New York. It changed its name to Rockefeller University in 1965 after expanding its mission to include graduate education.

It claims a connection to 23 Nobel laureates. He founded the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission in 1909, an organization that eventually eradicated the hookworm disease that had long plagued the American South.

The Rockefeller Foundation was created in 1913 to continue and expand the scope of the work of the Sanitary Commission, which was closed in 1915. He gave nearly $250 million to the foundation, which focused on public health, medical training, and the arts.

It endowed the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health with the first of its kind. It built the Peking Union Medical College into a great institution, helped in World War I war relief, and employed William Lyon Mackenzie, King of Canada, to study industrial relations. Rockefeller's fourth main philanthropy, the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial Foundation, created in 1918, supported work in social studies; it was later absorbed into the Rockefeller Foundation. However, all told, Rockefeller gave away about $550 million.

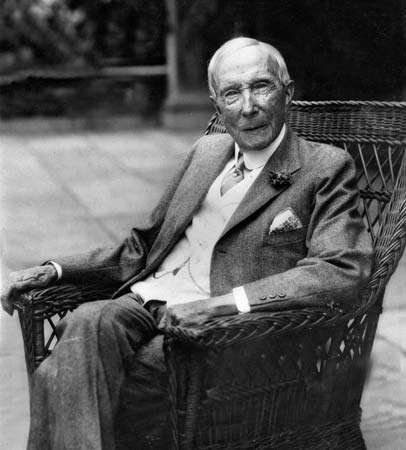

Oddly enough, Rockefeller was probably best known in his later life for the practice of giving a dime to children wherever he went. He even gave dimes as a playful gesture to men like tire mogul Harvey Firestone and President Herbert Hoover. During the Great Depression, Rockefeller switched to giving nickels instead of dimes.

Death

He died on May 23, 1937, 26 months shy of his 100th birthday. Rockefeller is buried in Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland, Ohio. Visitors to the gravesite often place dimes at the base of the stone, perhaps hoping that their money will increase as Rockefeller's did.

Rockefeller had a long and controversial career in industry, followed by a long career in philanthropy. His image often depended on what side of him you fell on.

These contemporaries include his former competitors, many of whom were driven to ruin, but many others of whom sold out at a profit (or a profitable stake in Standard Oil, as Rockefeller often offered his shares as payment for a business) and quite a few of whom became very wealthy as managers as well as owners in Standard Oil.

They also include politicians and writers, some of whom served Rockefeller's interests and some of whom built their careers by fighting Rockefeller and the "robber barons."

John D. Rockefeller's contributions to American ingenuity, capitalism, and entrepreneurship live on today.