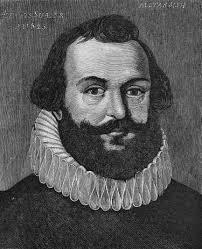

Myles Standish was born in 1584 in Lancashire, England, and would eventually become an English military officer appointed to the Pilgrims. His ability as a soldier has become legendary, and his techniques used in the New World ranged from respectable to brutal, which offended those closest to him. He would be elected as the leader of the military of Plymouth Colony until the end of his life.

Jump to:

Myles Standish Facts: Early Life

There is not much known about the early life of Myles Standish. It is believed he was born in Lancashire, England, but his childhood has been lost to history.

The circumstances are vague at best concerning Standish's early military career in Holland (the "low countries" to which Morton referred). At the time, the Dutch Republic was embroiled in the Eighty Years' War with Spain. Queen Elizabeth I of England chose to support the Protestant Dutch Republic and sent troops to fight the Spanish in Holland. Historians are divided on his role in the English military. Nathaniel Philbrick refers to Standish as a "mercenary," suggesting that he was

a hired soldier of fortune-seeking opportunity in Holland, but Justin Winsor claims that Standish received a lieutenant's commission in the English army and was subsequently promoted to captain in Holland. He still had the title Captain in 1620 when the Pilgrims arrived in the New World.

Myles Standish Facts: Plymouth Colony

The voyage to Cape Cod was not easy. The Pilgrims set sail with two boats, the Speedwell and the Mayflower, with the Speedwell falling apart and everyone being required to board the Mayflower. The journey across the Atlantic took two months with some rough weather. Once arrived, the Pilgrims would be required to outlast the first winter.

On November 9, 1620, lookouts spotted land, but it was quickly appreciated that their location was about 200 miles east-northeast of their planned destination of northern Virginia, near what is now called Cape Cod. They tried briefly to sail south, but strong seas forced them to retreat to Cape Cod to harbor near the "hook" of present-day Provincetown Harbor. It became apparent that the weather would not permit the passage south, so they decided to settle near Cape Cod. Shortage of supplies and the roaring Atlantic made it too dangerous to press on for a Virginia landing. They anchored at the hook on November 11, but not before signing a significant document. The leaders of the colony wrote the Mayflower Compact to ensure a degree of law and order in this place where they had not been granted a patent to settle. Myles Standish was one of the 41 men who signed the document.

Myles Standish Facts: Military Career

Contact with the Native Americans came in March 1621 through Samoset, an English-speaking Abenaki who arranged for the Pilgrims to meet with Massasoit, the sachem of the nearby Pokanoket tribe. On March 22, the first governor of Plymouth Colony, John Carver, signed a treaty with Massasoit, declaring an alliance between the Pokanoket and the Englishmen and requiring the two parties to defend each other in times of need. Governor Carver died the same year, and the responsibility of upholding the treaty fell to his successor, William Bradford. Bradford and Standish were frequently preoccupied with the complex task of reacting to threats against both the Pilgrims and the Pokanokets from tribes such as the Massachusetts and the Narragansetts. As threats arose, Standish typically advocated intimidation to deter their rivals. Such behavior at times made Bradford uncomfortable, but he found it an expedient means of maintaining the treaty with the Pokanokets.

Myles Standish had five main hurdles to overcome:

- Nemasket Raid: The first challenge to the treaty came in August 1621 when a sachem named Corbitant began to undermine Massasoit's leadership. Standish planned to attack Corbitant and kill him and decided that a night attack would be best. That night, he and Hobbamock burst into the shelter, shouting for Corbitant. As frightened Pokanokets attempted to escape, Englishmen outside the wigwam fired their muskets, wounding a Pokanoket man and woman who were later taken to Plymouth to be treated. Standish soon learned that Corbitant had already fled the village, and Tisquantum was unharmed. Standish had failed to capture Corbitant, but the raid had the desired effect. On September 13, 1621, nine sachems came to Plymouth, including Corbitant, to sign a treaty of loyalty to King James.

- Palisade: In November 1621, a Narragansett messenger arrived in Plymouth and delivered a bundle of arrows wrapped in a snakeskin. The Pilgrims were told by Tisquantum and Hobbamock that this was a threat and an insult from Narragansett sachem Canonicus. Taking the threat seriously, Standish urged that the colonists encircle their small village with a palisade made of tall, upright logs. The defense took three months to build, and it was effective. The attack on the village did not happen.

- Wessagusset: the Massachusett tribe threatened the settlers in Plymouth in 1620. Standish arranged to meet with Pecksuot over a meal in one of Wessagusset's one-room houses. Pecksuot brought with him a third warrior named Wituwamat, Wituwamat's adolescent brother, and several women. Standish had three men of Plymouth and Hobbamock with him in the house. On an arranged signal, the English shut the door of the house, and Standish attacked Pecksuot, stabbing him repeatedly with the man's own knife. Wituwamat and the third warrior were also killed. Leaving the house, Standish ordered two more Massachusett warriors to be put to death. Gathering his men, Standish went outside the walls of Wessagusset in search of Obtakiest, a sachem of the Massachusett tribe. The Englishmen soon encountered Obtakiest with a group of warriors, and a skirmish ensued, during which Obtakiest escaped. Standish would be criticized for his brutality, but his tactics managed to keep the colonists safe.

- Merrymount Settlers: In 1625, another threat appeared when a group of men established an outpost outside the city. Standish arrived with a group of men to find that the small band at Merrymount had barricaded themselves within a small building. Morton eventually decided to attack the men from Plymouth, but the Merrymount group was too drunk to handle their weapons. Morton aimed a weapon at Standish, which the captain purportedly ripped from his hands. Standish and his men took Morton to Plymouth and eventually sent him back to England. Later, Morton wrote the book New English Canaan, in which he referred to Myles Standish as "Captain Shrimp" and wrote, "I have found the Massachusetts Indians more full of humanity than the Christians."

- Penobscot Expedition: Standish's last significant expedition was against the French, having defended Plymouth from Native Americans and Englishmen. The French established a trading post in 1613 on the Penobscot River in what is now Castine, Maine. English forces captured the settlement in 1628 and turned it over to Plymouth Colony. It was a valuable source of furs and timber for the Pilgrims for seven years. However, in 1635, the French mounted a small expedition and easily reclaimed the settlement. William Bradford ordered Captain Standish to take action and determined that the post be reclaimed in Plymouth Colony's name. This was a significantly larger proposition than the small expeditions that Standish had previously led, and to accomplish the task, he chartered the ship Good Hope, captained by a man named Girling. Standish's plan appears to have been to bring the Good Hope within the cannon range of the trading post and to bombard the French into surrender. Unfortunately, Girling ordered the bombardment before the ship was within range and quickly spent all the gunpowder on board. Standish gave up the effort.

Myles Standish Facts: The End

During the 1640s, Standish took on an increasingly administrative role. He served as a surveyor of highways, as Treasurer of the Colony from 1644 to 1649, and on various committees to lay out boundaries of new towns and inspect waterways. His old friend Hobbamock had been part of his household, but he died in 1642 and was buried on Standish's farm in Duxbury.

Standish died on October 3, 1656, of "strangullion" or strangury, a condition often associated with kidney stones or bladder cancer. He was buried in Duxbury's Old Burying Ground, now known as the Myles Standish Cemetery.