Otto von Bismarck was a German statesman who led Prussia, was the architect who unified Germany, and served as its first chancellor.

In domestic affairs, he strengthened the economy, fought the Catholics and socialists, and began the German welfare state.

He played a major diplomatic role in world affairs, from leading the war against France in 1870-71 to balancing the major nations against each other so as to prevent war.

This was the "Bismarck System," but he was dismissed in 1890 by an arrogant new emperor who was oblivious to Bismarck's great achievements.

Jump to:

Early career

Bismarck was born to a Prussian junker family in Schönhausen, just east of the Elbe in Brandenburg. The Bismarck family was ancient but undistinguished.

Bismarck's mother, born Wilhelmine Menken, came from a Prussian civil service family, and her father had been a close advisor to Frederick the Great.

Her intelligence, learnedness, and attraction to city life made her ill-suited to her husband, Ferdinand von Bismarck's leisurely country lifestyle.

Otto took after his mother but resented her coldness and admired his father, whom he idolized as an exemplar of the Prussian junker tradition.

As A.J.P. Taylor writes, "He was the clever, sophisticated son of a clever, sophisticated mother, masquerading all his life as his heavy, earthy father."

Bismarck, at age 7, was sent to the best grammar school in Berlin.

Thanks to his family connections to the royal house, Bismarck came into close contact with younger members of the royal family, including the crown prince Frederick William, and his younger brother, the future William I, whom he would later serve for nearly thirty years.

Bismarck attended the University at Göttingen, where he led a riotous student lifestyle, drinking and fighting duels.

Here, he adopted the reactionary politics that would characterize his early years.

He spent a year at the University of Berlin. In May 1835, at the age of 20, Bismarck entered the Prussian civil service.

Bismarck was first sent to Aachen, in the Rhineland, where he spent several years ignoring his duties and falling in love with a series of English girls.

After abandoning his post to follow one girl around Germany for three months, Bismarck joined the army for his compulsory year of service as an officer in Potsdam.

There, he renewed his acquaintance with members of the Prussian royal family. After leaving the army in 1839, Bismarck resigned from the civil service.

Bismarck took up the lifestyle of a Prussian junker in managing the family's Pomeranian estates, remaining there for eight years.

He married Johanna von Puttkamer and found religion, adopting a quietist Lutheranism that would remain with him for the rest of his life.

In 1847, Bismarck was appointed to the Prussian legislature, and after the 1849 constitution, he was elected to the lower house of the new Prussian Parliament, the Landtag.

While there, he opposed the German unification movement because Austria was poised to be its new leader.

As a result, Bismarck was elected by the Landtag to represent Prussia at the Erfurt Parliament to oppose the unification movement vigorously.

Diplomat

In 1852, Bismarck was sent to Frankfurt as the Prussian representative of the German Confederation.

Here, he continued his position of opposition to Austria's German policy, helping to stymie Austrian efforts to seek German diplomatic support for its position in the Crimean War.

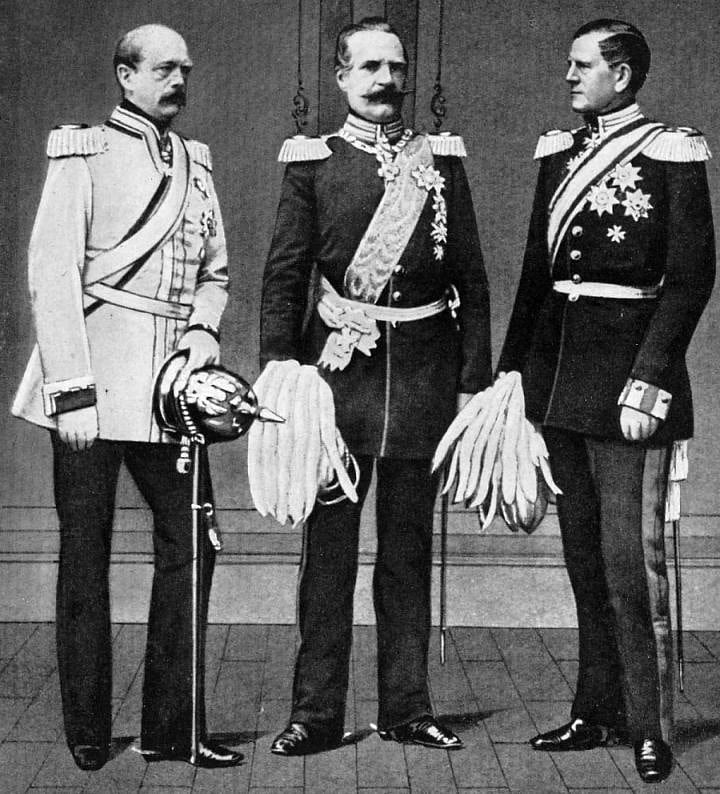

In 1858, Prince Wilhelm took over as regent. Wilhelm, recognizing Bismarck's ability, appointed him as ambassador to the Russian court in Saint Petersburg.

At the same time, Wilhelm also appointed Helmuth von Moltke as Chief of the Prussian General Staff and Albrecht von Roon as Minister of War.

Roon, in particular, would become a close ally of Bismarck, helping to keep Bismarck informed about Prussian internal politics while he was at the Russian court.

Premier of Prussia

In 1862, the dominant Liberals in the Landtag clashed with Wilhelm (now King William I) over the king's budget and military spending. In the Prussian Parliament, like most other parliaments, power lay in its control of the allocation of the Prussian treasury.

The liberals threatened not to pass the budget and thus not give any money to the government unless Wilhelm reduced military spending.

This led to a crisis, with the elderly king seriously considering abdication over the issue. Roon and other conservative Prussian politicians urged the appointment of Bismarck as Prime Minister, arguing that he was the only man who could take on parliament and defeat it over the issue.

Bismarck, however, insisted that he would only take over if he was given complete control over both domestic and foreign affairs.

The king balked at this instead of sending Bismarck to Paris as ambassador at the court of the French emperor Napoleon III.

However, in late 1862, the Landtag resoundingly rejected a proposed compromise from William I, so he appointed Bismarck as both prime minister and foreign minister.

Bismarck took office and declared that because the constitution did not cover the situation of what would happen if the Landtag refused to approve a budget, then the budget from the previous year would come into effect; legally, this was a fuzzy issue.

The Landtag protested to the king to no avail. Taxes were collected under the 1861 budget, so the Landtag passed a resolution that it could never work with Bismarck and demanded a new prime minister. The king dissolved the Landtag.

To silence the liberal protests to this, Bismarck issued edicts restricting the freedom of the press; he remained unpopular, and over ⅔ of the seats in the Landtag went to liberals in the next election.

However, the King stuck with Bismarck throughout the storm of criticism.

War with Denmark

In 1863, the King of Denmark died. This caused contention because two duchies, Schleswig and Holstein, were claimed both by Denmark and by a German duke.

The German people resoundingly demanded that the German duke get the territories, whereas Denmark was in the process of writing a new constitution that would make Schleswig officially part of Denmark.

There were several issues at play.

Holstein was both German-speaking and ethnic in origin, while Schleswig was mixed between German and Danish.

Holstein was a member of the German Confederation, while Schleswig was not. The Treaty of Ribe mandated that the two provinces could not be separated.

Finally, the German Liberal Nationalists were agitating for the German duke to take over the two provinces as one separate German nation.

In response to this, seeing a ripe opportunity to gain territory and prestige, Bismarck declared openly that Prussia supported the Danish claim to the duchies, but at the same time, said that Prussia would not tolerate Schleswig becoming a part of Denmark under the new constitution.

Denmark rejected this, and Prussia, with the support of Austria-Hungary, declared war and defeated the Danes in the Second War of Schleswig.

As a result, Denmark ceded authority over the control of the provinces. However, rather than turn the issue over to the German Confederation, which would likely vote to give the provinces to the Duke, who laid claim to the provinces, Bismarck convinced the Austrian Empire to split the administration of the two provinces between them under the Gastein Convention.

In this way, Bismarck was able to squelch liberal nationalism while at the same time gaining control of the provinces from Denmark and was able to set the stage for the Austro-Prussian War.

War with Austria

Bismarck still wanted to unify Germany, but Austria-Hungary and particularly the Austrian-dominated "German Confederation" stood in his way. In order to unify Germany, Bismarck needed a way around them, and to this effect, he used the splitting of Schleswig and Holstein.

Holstein went to the Austrians, while Schleswig (the mixed duchy) went to the Prussians. Bismarck then used the press to agitate the people of Holstein against the Austrians, who he portrayed as foreign occupiers, and further sold the story to the Prussian and North German Countries.

Alarmed by the growing discontent in Holstein, the Austrians demanded that the issue of control over Schleswig and Holstein be settled by the German Confederation.

Bismarck jumped at this, saying that the Austrians had violated the Gastein Convention and declared war.

Most of the small southern German States sided with Austria in this, while the northern German states sided with Prussia, along with Italy (which wanted to reclaim Venetia from Austria).

The Austro-Prussian war was short and victorious.

Moltke and Von Roon had reorganized the Prussian army, turned it into an exceptionally effective fighting machine, and defeated Austria in The Seven Weeks War.

Austria was humiliated, but rather than press on, Bismarck got Wilhelm to stop the war early and forced Austria to cede all of its German possessions.

The result of the war was threefold: first, Austria was no longer a player in German politics; second, the German confederation was disbanded; and third, Prussia was acknowledged as the new leader of Germany internationally.

To solidify his successes, Bismarck's North German Confederation was a federation between the Northern German allies from the last war and Prussia, with Prussia at its head with King Wilhelm as President and Bismarck as chancellor.

This successful war ended the domestic disturbances at home, helped Bismarck's supporters into the Prussian Landtag, and provided support to Bismarck in the times to come.

War with France, 1870-71

With the Liberals squelched at home, for now, Austria was out of the picture, and North Germany united. Bismarck just needed a way to get the southern German states under Prussian control.

The only feasible way Bismarck saw to do this was to have a foreign power invade Germany and for Germany to unify to face the threat.

Then Prussia could seize the opportunity to unify as one nation under that system permanently. The chance arrived in 1870 when the throne of Spain was offered to a relative of the Hohenzollern clan.

Napoleon the Third announced not only that he would not stand for his candidacy for the throne but demanded that King Wilhelm promise never to allow a member of the Hohenzollern family to ascend to the Spanish throne.

Wilhelm wrote a cordial reply to Napoleon saying that while he would not remove his support from the candidate immediately, he would be willing to discuss the issue with Napoleon.

Bismarck, however, took the telegram, edited it so as to read as an affront to Napoleon, and leaked it to the press in the famous Ems Dispatch.

The French reacted vehemently and, in a national uproar, declared the Franco-Prussian war. Seeing them as an aggressor, the entirety of Germany rallied behind Prussia, and Prussia defeated the French invasion force, counter-invaded, and utterly defeated France, all in under a month.

France was forced to pay a large indemnity to Prussia and surrender the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine.

Bismarck used the opportunity to unify Germany and, through a variety of incentives, got the southern German states to agree to form a German Empire with Prussia as Primus inter Pares (first among equals) and King Wilhelm as the first German Emperor.

Chancellor of United Germany, 1871-1890

With William I now "Emperor of the Germans," Bismark became "Chancellor of the German Empire." Bismarck dominated the elderly Emperor, who protested, "It is not easy to be emperor under such a chancellor."

Popularly hailed as the "Iron Chancellor," the man of the minority and absolutism, had to govern this empire from 1871 to 1890 with the advice and consent of a Reichstag representing the majority. His only supporters in the Reichstag were the Liberals.

Bismarck reformed German law, administration, and finance. In 1873, his educational reforms provoked conflict with the Roman Catholic Church, though behind it lay the larger issue of the newly militant German Catholics' suspicion of Protestant Prussia.

When this antagonism was expressed in the Reichstag's Catholic Center Party, it alarmed Bismarck, and he launched an anti-Catholic Kulturkampf (struggle for civilization).

In its course, bishops and priests were imprisoned, and dioceses remained empty.

In foreign affairs, Bismarck sought a complex, ever-changing balance of power that would keep the world at peace while promoting Germany's economic growth.

Tactically, he tried to keep France diplomatically isolated and to prevent any anti-Germany coalition from forming.

He avoided involvement in the tottering Turkish Empire, called the "Eastern Question," and in 1878, presided at the Congress of Berlin, acting as an "honest broker" between the contending parties.

The secret treaty with Russia illustrated Bismarck's ability to deal behind the backs of his allies, Austria and Italy, for the protection of the status quo in the Near East.

Until 1884, Bismarck did not enunciate a clearly defined colonial policy, principally for fear of offending Britain.

Conserving German capital and maintaining administrative costs at a minimum were other factors. His first plans for expansion met vigorous opposition from all parties: Catholics, advocates of states' rights, Socialists, and even his own class, the Junkers.

Nevertheless, he did endow Germany with the beginnings of a colonial empire.

In 1879, Bismarck broke with the Liberals and relied instead on an uneasy coalition of landowners (especially junkers) and industrialists; "blood and iron," it was called.

He gradually ended the Kulturkampf and turned his attention instead to the Socialists. To prove conservatives were the best guardian of the people's welfare, he introduced state insurance for sickness in 1883, for accidents in 1884, and for old age in 1889.

These programs, designed by Theodor Lohmann, represented the first appearance of the modern welfare state; Bismark's model was copied by the Liberals in Britain about 1910 and the Democrats in the U.S. in the 1930s.

While Bismarck's programs did not detach the German workers from the Social Democratic Party; they did show how workers could be wooed by revolutionary methods, and the German Socialists came to embrace evolutionary reform ("revisionism") rather than revolution.

Bismark kept the support of his industrialist supporters by opposing any regulation of working conditions.

Resignation

The arrogant. militaristic young William II (1859-1941) became Kaiser in 1888 and paid little heed to Bismarck.

Their most serious quarrel developed over the renewal of the anti-Socialist laws and the rights of subordinate cabinet ministers to a personal audience with the Emperor.

William II obtained Bismarck's resignation on March 18, 1890.

The world was stunned at the sudden departure of the man credited with keeping the peace in Europe for two decades.

Death

Bismarck spent his final years composing his memoirs (Gedanken und Erinnerungen, or Thoughts and Memories), a work lauded by historians.

In the memoirs, Bismarck continued his feud with Wilhelm II by attacking him by increasing the drama around every event and often presenting himself in a favorable light.

He also published the text of the Reinsurance Treaty with Russia, a major breach of national security for which an individual of lesser status would have been heavily prosecuted.

Bismarck's health began to fail in 1896. He was diagnosed with gangrene in his foot but refused to accept treatment for it; as a result, he had difficulty walking and often used a wheelchair.

By July 1898, he was a full-time wheelchair user, had trouble breathing, and was almost constantly feverish and in pain. His health rallied momentarily on the 28th but then sharply deteriorated over the next two days.

He died just after midnight on 30 July 1898, at the age of eighty-three, in Friedrichsruh, where he was entombed in the Bismarck Mausoleum.

He was succeeded as Prince Bismarck by his eldest son, Herbert.

Bismarck managed a posthumous snub of Wilhelm II by having his own sarcophagus inscribed with the words, "A loyal German servant of Emperor Wilhelm I"