Samuel Sewall was a judge during the Salem Witch Trials that took place in Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1692. He would become one of the judges who would come out later and apologize for his participation in the trials.

After the trials, he would become known as one of Colonial America's first abolitionists.

Early Years

Samuel Sewall was born in England to Henry and Jane Sewall. His father, son of the Mayor of Coventry, had come to the English North American Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1635, where he married Sewall's mother and returned to England in the 1640s.

After Charles II took back the throne of England, the Sewall family migrated over to the colonies for good.

Like other local boys, he attended school at the home of James Noyes, whose cousin, Reverend Thomas Parker, was the principal instructor. From Parker, Sewall acquired a lifelong love of verse, which he wrote in both English and Latin.

In 1667, Sewall entered Harvard College, where his classmates included Edward Taylor and Daniel Gookin, with whom he formed enduring friendships. Sewall received his first degree, a BA, in 1671 and his MA in 1674.

In 1674, he served as librarian of Harvard for nine months, the second person to hold that post. That year, he began keeping a journal, which he maintained for most of his life; it is one of the major historical documents of the time.

In 1679, he became a member of the Military Company of Massachusetts.

Sewall's involvement in the political affairs of the colony began when he became a freeman of the colony, giving him the right to vote. In 1681, he was appointed the official printer of the colony. One of the first works he published was John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress.

After John Hull died in 1683, Sewall was elected to replace him on the colony's council of assistants, a body that functioned both as the upper house of the legislature and as a court of appeals. He also became a member of Harvard's Board of Overseers.

Sewall's oral examination for the MA was a public affair and was witnessed by Hannah Hull, daughter of colonial merchant and mintmaster John Hull. She was apparently taken by the young man's charms and pursued him. They were married in February 1676.

Her father, whose work as mintmaster had made him quite wealthy, gave the couple a large sum of money to begin their married life.

Sewall moved into his in-laws' mansion in Boston and was soon involved in that family's business and political affairs.

He and Hannah had fourteen children before her death in 1717, although only a few survived to adulthood.

Salem Witch Trials

Samuel had held a position of assistant magistrate for a bit of time before 1692 when the Salem Witch Trials broke out. Due to his experience, he became one of the nine judges appointed to the Court of Oyer and Terminer by Governor Phips.

He participated in and documented some of the trials. One of those that he documented was the death of Giles Corey by pressing.

In his diary, he also speaks about the public's feelings about the guilt of many who were accused. He seems to say that the public was uncomfortable with the growing list of those who were executed.

Sewall's brother Stephen had meanwhile opened up his home to one of the initially afflicted children, Elizabeth Parris, daughter of Salem Village's minister, Samuel Parris, and shortly afterward, Betty's "afflictions" appear to have gone away.

He deeply regretted his role in the trials and called for a day of public prayer and fasting.

After the trials ended, Sewall and his family endured much tragedy with the death of two of his daughters and his mother-in-law. His wife then gave birth to a stillborn baby. These tragedies led to Sewall believing that he had caused this and it was a punishment from God.

He then repented publicly for his actions.

Not only had Sewall's home life been rough, but in the years after the trials, the people of Massachusetts came to see them as the culmination of a generation-long series of setbacks and ordeals, notably the Navigation Acts, the declaration of the New England Dominion, and King Philip's War.

He saw this as a sign not that witchcraft did not exist but that he had ruled on insubstantial evidence known as spectral evidence.

He records in his diary that on January 14, 1697, he stood up in the meeting house he attended while his minister read out his confession of guilt.

His response was much different than that of Nathaniel Hathorne, Jonathan Corwin, William Stoughton, and even Cotton Mather, who seemed not to care or even defend their positions

Samuel Sewall the Abolitionist

Slavery was not as common in New England as it would be in the South, but it still existed, evidenced by three slaves being accused of witchcraft: Tituba, Candy, and Mary Black.

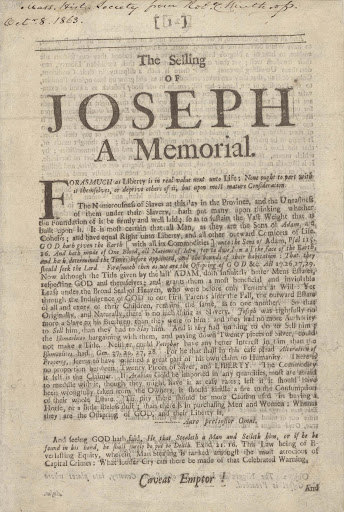

In his writing, The Selling of Joseph Sewell argued, "Liberty is in real value next unto Life: None ought to part with it themselves or deprive others of it but upon the most mature Consideration." He regarded "man-stealing as an atrocious crime which would introduce among the English settlers people who would remain forever restive and alien," but also believed that "There is such a disparity in their Conditions, Colour, Hair, that they can never embody with us, and grow up into orderly Families, to the Peopling of the Land." Although holding such segregationist views, he maintained that "These Ethiopians, as black as they are; seeing they are the Sons and Daughters of the First Adam, the Brethren, and Sisters of the Last ADAM [meaning Jesus Christ], and the Offspring of God; They ought to be treated with a Respect agreeable."

He was prophetic for his time, as the introduction of slavery to the United States would create a dependence on forced labor, especially in the Southern Colonies. His ideas were forward-thinking because he leaned on the scripture and how God intended for Christians to treat one another and others.

Jesus said that others would know Christians by how they "Loved one another."

The Bible account of creation, which Sewall references, says that mankind comes from one person and that race is a social construct that has been created by individuals.

Samuel Sewall died on January 1, 1730.