The Second Battle of the Aisne was the main action of the Nivelle Offensive and was a disaster for the French Army during World War 1.

The attack involved 1.2 million troops and 7,000 guns but achieved little territorial gain and brought an end to the career of its instigator, French Commander-in-Chief Robert Nivelle. It also sparked widespread mutiny in the army.

Nivelle’s plan was devised upon his appointment as Commander-in-Chief in December 1916, replacing Joseph Joffre.

He confidently assured the French government that it would bring about an end to the war within two days, but it was beset by delays and leaks. By the time of its main launch on April 16, 1917, the plans were well-known to the German Army, who accordingly took appropriate defensive steps.

Nivelle’s strategy did not receive unanimous support among influential French politicians. Whilst Prime Minister Briand’s support effectively sanctioned the plan, it led to the resignation of war minister Hubert Lyautey.

The British Commander-in-Chief, Sir Douglas Haig, expressed his opposition, as did Nivelle’s successor as Commander-in-Chief, Henri-Philippe Petain. Even Nivelle’s Reserve Army Group commander, General Micheler, was opposed.

The Battle

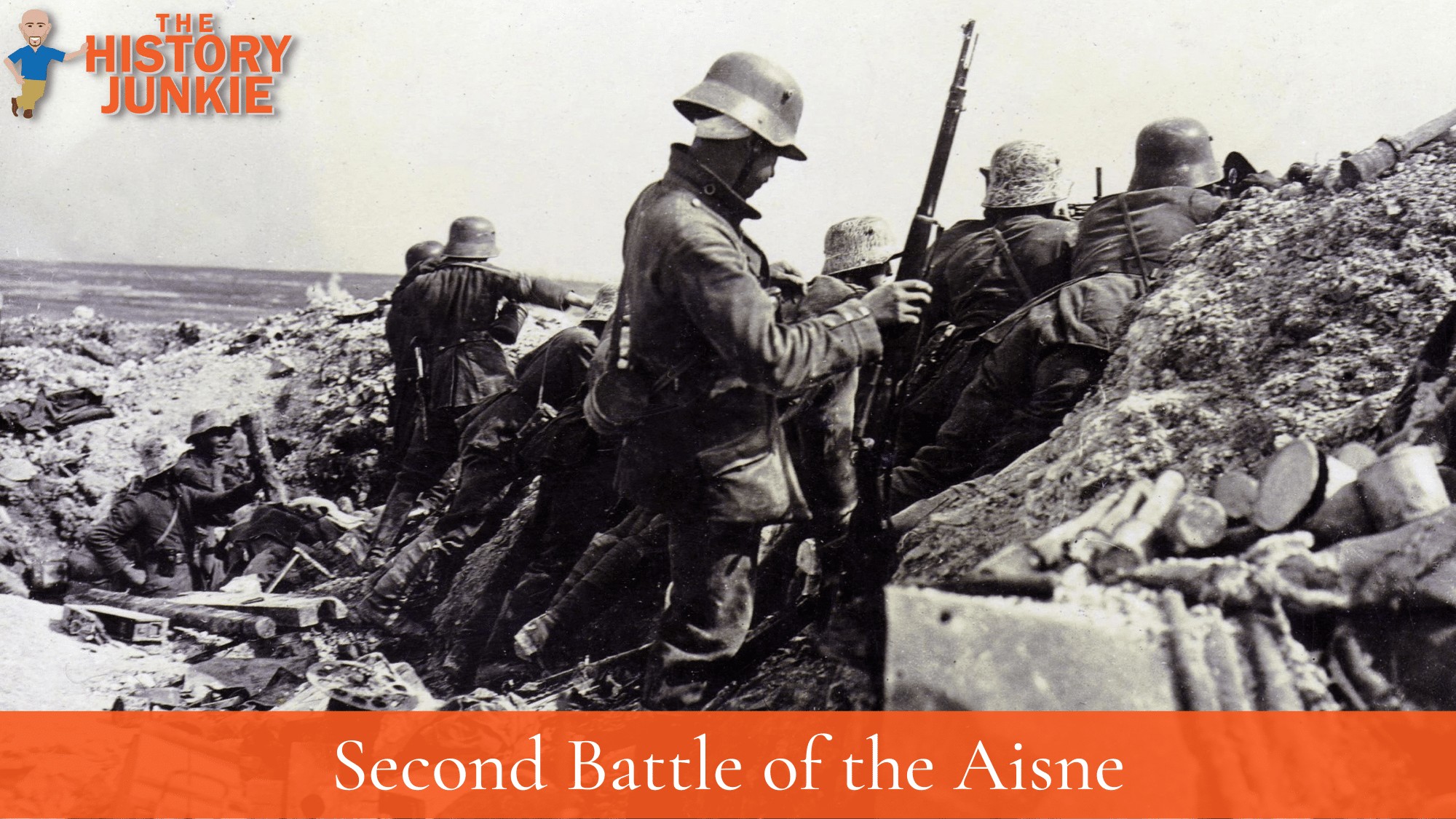

On April 17, 1917, 19 divisions of the French Fifth and Sixth Armies - under Mazel and Mangin - went into battle along a 50-mile front from Soissons to Reims after a week of diversionary attacks by the British in Arras.

Opposite them on high ground was von Boehm’s German Seventh Army, which conducted an efficient defense.

The French suffered 40,000 casualties alone on that day - a similar disaster to that suffered by the British on the first day of the Battle of Somme a year earlier on July 1, 1916. The mass use of French Char Schneider tanks brought little advantage, with 150 lost on the first day.

On the second day, the French Fourth Army under Anthoine launched a subsidiary attack east of Reims towards Moronvilliers, but von Below’s German First Army readily repelled it.

Ironically, in the attacks of April 16 and 17th, Nivelle’s own innovation - the creeping barrage - was incorrectly deployed, leading to increased French casualties as the infantry advanced without protection.

Despite evidence to the contrary, Nivelle believed his offensive would ultimately prove successful and continued French attacks until April 20. Some gains were made by Mangin west of Soissons, but progress was slow.

The offensive was scaled back over the next two weeks, although by May 5, a 2.5-mile stretch of the Chemin des Dames Ridge - part of the Hindenburg Line - had been captured. The offensive was finally abandoned in disarray on May 9, following a final ineffective four-day assault.

French losses were significant, with 187,000 casualties, while Germans suffered an estimated 168,000 losses.

At home, disillusion among the French public and politicians alike led to Nivelle’s prompt removal being replaced on April 25 by considerably more cautious Henri-Philippe Petain, who restored order within the French Army by improving trench conditions and refraining from committing his forces to offensive operations.