In 1914 and 1915, the Germans attacked the Allies at Ypres twice. But in 1917, Sir Douglas Haig planned to break through the German lines in Flanders with his Allied forces. This was the Third Battle of Ypres in World War 1.

Flanders was Haig’s preferred location for a big attack in 1916, but he had to fight at the Somme instead that summer.

He finally launched his Flanders offensive on July 31, 1917, and it lasted until November 6, when Passchendaele village fell. The Allies made some progress but not as much as Haig wanted, and they paid a high price in their lives.

Jump to:

Prelude

The Third Battle of Ypres is also known as ‘Passchendaele,’ and it is as disputed as the Battle of Somme for the way Haig fought it. It was the last huge battle of wearing down the enemy in the war.

After the French failed badly in the Nivelle Offensive in May and their army started to mutiny, Haig decided to go ahead with his plans for a big British attack in late summer.

He said he wanted to destroy the German submarine bases on the Belgian coast because British Admiral Jellicoe warned that the British could not keep up the war into 1918 if they kept losing ships.

But Haig also wanted to break the German army, which he thought was close to giving up - a wrong idea that he also had at the Somme a year before.

British Prime Minister David Lloyd George did not like the Passchendaele offensive and later criticized Haig’s strategy and tactics in his books, but he did not have anyone else to replace Haig, so he let him do what he wanted.

He was, however, happy with the biggest local success of the war earlier that summer, on June 7, at Messines Ridge, when General Plumer took the whole Messines-Wytschaete ridge in the Battle of Messines. Taking the ridge was needed before an attack took Passchendaele Ridge.

Plumer wanted to keep attacking Passchendaele Ridge right away because he said the German troops were very low in spirit and numbers, and the Allies could easily take the ridge. But Haig did not agree and waited until the end of July for his plans.

With the Russian forces very shaky and maybe leaving the war soon, it seemed important to do something in the summer of 1917. If the Russians left the war, Germany could move its Eastern forces to fight on the Western Front and have a lot more reserves.

The Battle

Sir Hubert Gough’s Fifth Army started the Third Battle of Ypres, with 1 Corps of Sir Herbert Plumer’s Second Army on its right and a corps of the French First Army led by Anthoine on its left: twelve divisions in total.

As usual for any big Allied attack, on July 18, they fired a lot of artillery shells for ten days before they attacked at 03:50 on July 31. They used 3,000 guns and fired over four million shells. The German Fourth Army, led by Arnim, knew an attack was coming soon; there was no surprise at all.

So when the attack came across an 11-mile front, the Fourth Army stopped most of the British advance around the Menin Road and only let the Allies take some small ground to the left of the line around Pilckem Ridge. The French were also stopped further north by the German Fifth Army under Gallwitz.

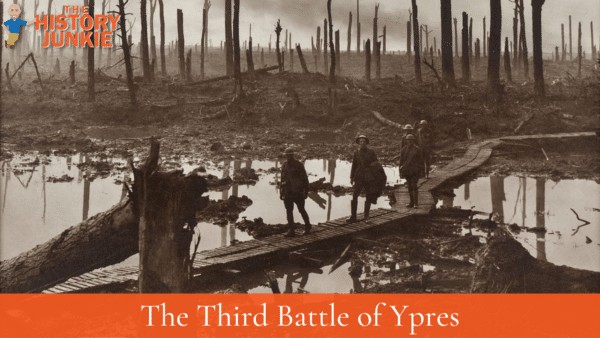

The British tried to keep attacking in the next few days, but it rained a lot, the most in 30 years, and the ground became very muddy. Tanks got stuck in the mud and could not move. The soldiers also had a hard time moving. The rain also made the problem worse because the artillery shells that had been fired before the attack had broken the drains and made holes in the ground.

So they had to wait until August 16 to start a big attack again, the Battle of Langemarck. It was a hard fight for four days, and the British only got a little ground but lost a lot of men.

Haig was not happy with how things were going, so he changed Sir Hubert Gough (by moving him and his forces to the north) with Herbert Plumer. Gough liked to attack a lot, but Plumer liked to plan small attacks instead of trying to break through all at once.

The new attacks started on September 20 with the Battle of the Menin Road Bridge. Then, there was the Battle of Polygon Wood on September 26 and the Battle of Broodseinde on October 4. These battles helped the British take the ridge east of Ypres.

Haig liked Plumer’s small attacks - but he always wanted him to do more - and he decided to keep attacking Passchendaele Ridge 6 miles from Ypres because he was sure that the German army was almost done.

But they did not get much closer to this goal at the Battle of Poelcappelle and the First Battle of Passchendaele on October 9 and October 12.

The Allied attackers were very tired, and the Germans had more reserves from the Eastern Front to defend the ridge. The Germans also used mustard gas (not like chlorine gas in The Second Battle of Ypres), which burned their skin.

Haig did not want to give up on breaking through, so he made three more attacks on the ridge in late October. The British and Canadian forces finally took Passchendaele village on November 6, and Haig stopped the offensive, saying he had won.

The Third Battle of Ypres was very expensive, like the ones before it. The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) lost about 310,000 men, and the Germans lost a bit less: 260,000.

Haig got a lot of blame, both in 1917 and later, for keeping up with the offensive when it was clear that he could not break through.

Conclusion

Some people say that he should have started the attack from Messines Ridge, which Plumer took in June, but Haig’s first plans did not include this; he only saw taking the ridge as something he had to do first, and he did not want to change his plans.

But there are also many reasons to support his decision to keep attacking into the autumn. With Russia leaving the war, British ships being attacked by submarines from the Belgian coast, and low French spirit, which showed up in many mutinies, it seemed like they had to try something big before they could not fight anymore.

Some people also say that the bad weather was not something they could have known: that it rained much more than usual. In fact, there had been fighting around Ypres since 1914 without the kind of trouble they had during the Third Battle of Ypres.

Haig himself said that if they looked at it as a battle of wearing down the enemy, the German forces had more to lose than the Allies, who by then had the U.S. on their side.

Some Germans at the time agreed with this.