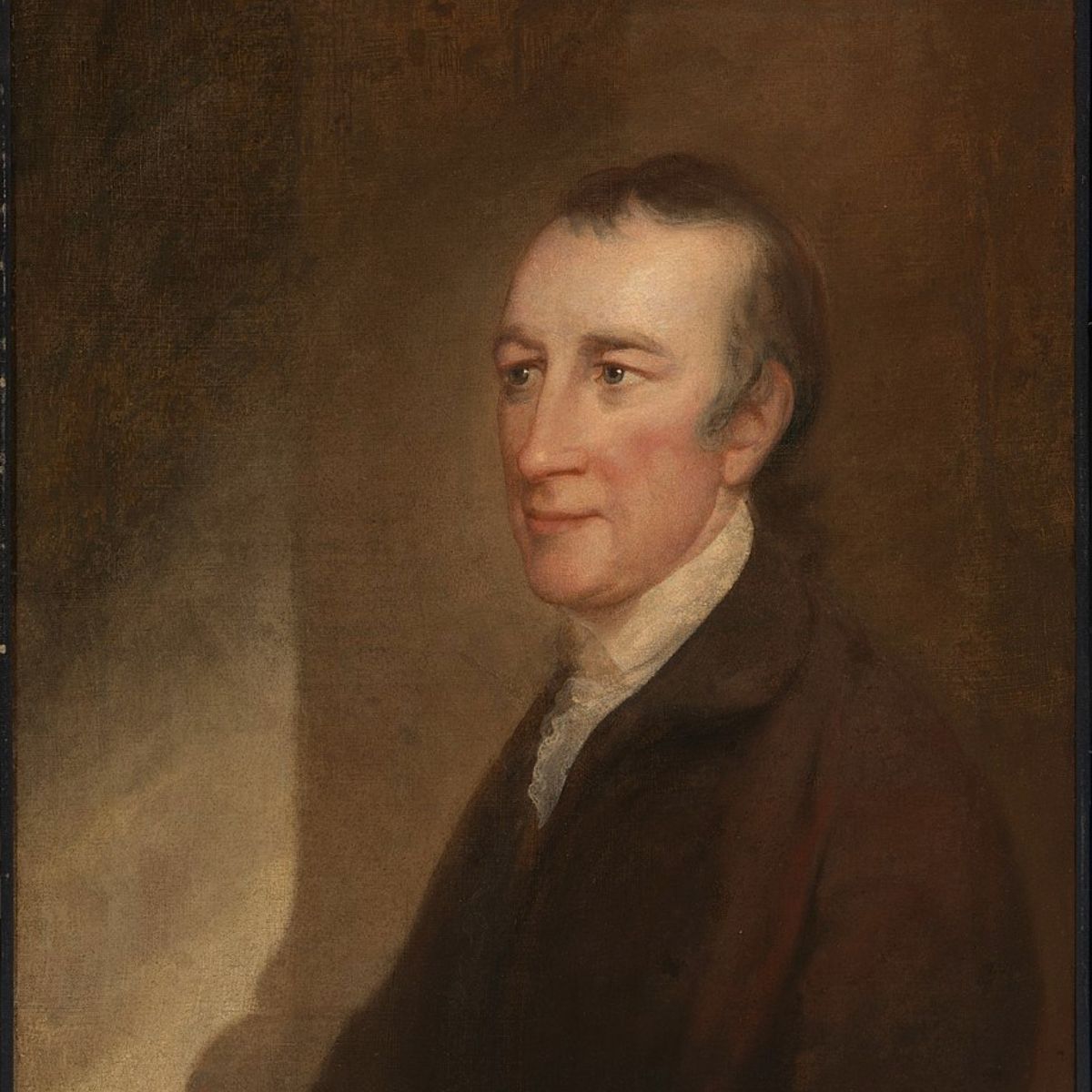

Thomas Stone (1743 – October 5, 1787) served as a delegate from Maryland in the Second Continental Congress. He, like many delegates, was a wealthy planter who owned slaves. His family had been a wealthy family in Maryland for a few generations, which afforded him some of the best education.

Stone seemed to show a fondness for learning and never took his privileges for granted. He studied extremely hard and would eventually become a lawyer. Thomas Stone served alongside his fellow Maryland delegates: Samuel Chase, William Paca, and Charles Carroll of Carrollton.

Maryland would be one of the first Middle Colonies to support the war for Independence from Britain.

Jump to:

Life and Career of Thomas Stone

Thomas Stone married the love of his life, Margaret Brown, in 1768. The two would share a life of friendship together. Margaret would give birth to three children, all of which would survive to adulthood. Stone purchased 400 acres and began to cultivate the land. He would go on to own one of the largest plantations in Maryland while also becoming one of its most prominent lawyers. He would employ his younger brother to run his plantation so he could focus on his law practice.

The Stamp Act became a lightning rod for independence and caused many of the prominent men of colonial society to begin to push for independence. Thomas Stone would join the Committee of Correspondence and would become a member of Maryland's Annapolis Convention. He would be elected to serve as a delegate to the Continental Congress and would eventually sign the Declaration of Independence, but it took some prodding.

Within the Continental Congress, there were differing factions. One faction did not want to go to war and was led by the poignant and influential Quaker from Pennsylvania, John Dickinson. Dickinson was a pacifist and did not believe in war, and wished to push for colonial reconciliation with Great Britain.

Thomas Stone would side with Dickinson. Stone did not want to sever ties with Great Britain for fear of a long and violent war. He was a bit of a pacifist, but not to the extreme that Dickinson was one. By May of 1776, Stone was convinced to sign the declaration. He did so and then returned home to a personal tragedy.

Most of the American Revolutionary War was spent at home by his wife's side. Margaret had been inoculated with smallpox, which had an adverse effect on her. She would never regain her health and would die in 1787. The loss was excruciating for Stone, and he would never recover. He would die of a broken heart shortly after while preparing a ship to sail to Alexandria. His plantation would stay in the family for five generations.

Shortly before his wife passed, Stone served in the Maryland Senate and pushed for the state to ratify the Articles of Confederation. The articles proved ineffective and would bring forth the Constitution. Stone would not live to see it.

Charles Goodrich says this about the tragedy that struck Thomas Stone and the events that followed:

In 1787, Mr. Stone was called to experience an affliction that caused a deep and abiding melancholy to settle upon his spirits. This was the death of Mrs. Stone, to whom he was justly and most tenderly attached. During a long state of weakness and decline, induced by injudicious treatment on the occasion of her having the smallpox by inoculation, Mr. Stone watched over her with the most unwearied devotion. At length, however, she sank to the grave. From this time, the health of Mr. Stone evidently declined. In the autumn of the same year, his physicians advised him to make a sea voyage, and in obedience to that advice, he repaired to Alexandria to embark for England. Before the vessel was ready to sail, however, he suddenly expired on the fifth of October, 1787, in the forty-fifth year of his age.

Mr. Stone was a professor of religion and was distinguished for his sincere and fervent piety. To strangers, he had the appearance of austerity, but among his intimate friends, he was affable, cheerful, and familiar. In his disposition, he was uncommonly amiable and well-disposed. In person, he was tall but well-proportioned.