With the failure of the German offensive against France at the First Battle of the Marne and the allied counter-offensive, the so-called 'race to the sea' began, a movement towards the North Sea coast as each army attempted to out-flank the other by moving progressively north and west.

As they went, each army constructed a series of trench lines, starting on September 15, that came to characterize war on the Western Front until 1918.

Meanwhile, French Commander-in-Chief Joseph Joffre undertook an intensive combined allied attack on September 14 against the German forces on the high ground just north of the Aisne River.

Jump to:

With the German defenses too strong, the attack was called off on September 18.

Stalemate had set in.

By October, the Allies had reached the North Sea at Niuwpoort in Belgium. German forces forced the Belgian army out of Antwerp, ultimately ending up in Ypres.

The Battle Begins

The British Expeditionary Force (BEF), under Sir John French, took over the line from Ypres south to La Bassee in France, from which point the French army continued the line down to the Swiss border.

Such was the background to the First Battle of Ypres, which commenced on October 14, when Eric von Falkenhayn, the German Chief of Staff, sent his Fourth and Sixth armies into Ypres.

The battle began with a nine-day German offensive that was only halted with the arrival of French reinforcements and the deliberate flooding of the Belgian front. Belgian troops opened the sluice gates of the dykes holding back the sea from the low countries.

The flood encompassed the final ten miles of trenches in the far north, which later proved a hindrance to the movement of Allied troops and equipment.

During the attack, British riflemen held their positions, suffering heavy casualties, as did French forces guarding the north of the town.

The second phase of the battle saw a counter-offensive launched by General Foch on October 20, ultimately without success. It ended on October 28.

Next, von Falkenhayn renewed his offensive on October 29, attacking most heavily in the south and east - once again without decisive success. Duke Albrecht's German Fourth Army had taken the Messines Ridge and Wytschaete by November 1.

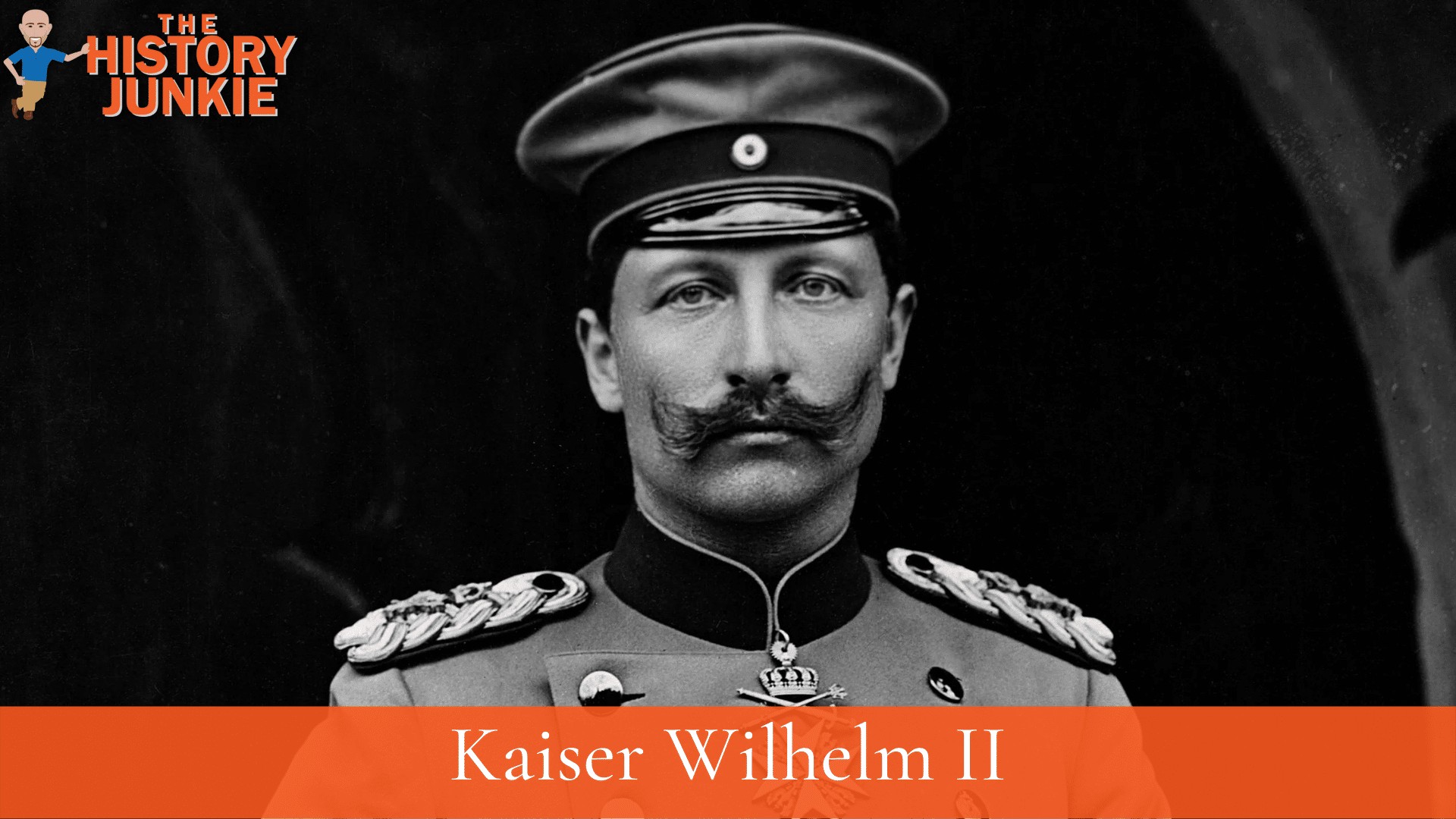

It also took Gheluvelt and managed to break the British line along the Menin Road on October 31. The defeat was imminent, and the German Kaiser Wilhelm II was shortly to arrive to personally witness the taking of the town.

However, the arrival of French reinforcements saved the town, and the British counter-attacking and recaptured Gheluvelt.

The German offensive continued for the following ten days, the fate of Ypres still in the balance. A further injection of French reinforcements arrived on November 4.

Even so, evacuation of the town seemed likely on November 9 as the German forces pressed home their attack, taking St Eloi on November 10 and pouring everything into an attempt to re-capture Gheluvelt on November 11-12, without success.

A final major German assault was launched on November 15; still, Ypres was held by the British and French. By this time, the Belgian autumn had set in with the arrival of heavy rain followed by snow. Von Falkenhayn called off the attack.

Aftermath

It was becoming evident that the nature of trench warfare favored the defender rather than the attacker. In short, the technology of defensive warfare was better advanced than that of offensive warfare, the latter proving hugely costly in terms of manpower.

The BEF had held Ypres, as they continued to do until the end of the war despite repeated German assaults; the Allies also held a salient extending 6 miles into German lines.

The cost had been huge on both sides.

British casualties were reported at 58,155, mostly pre-war professional soldiers, a loss the British could ill afford. French casualties were set at around 50,000, and German losses at 130,000 men.