Amerigo Vespucci is known to American schoolchildren because America is named after him.

He grew up around the time of Christopher Columbus and would eventually work himself into a position that allowed him to sail to the New World.

Also Read: Christopher Columbus Timeline

His studies from his earlier years gave him the knowledge he needed for his years of discovery.

Jump to:

- 1. Amerigo Vespucci was Born to an Affluent Italian Family

- 2. He was Educated by His Uncle

- 3. He Worked for the Medici Family

- 4. He Sailed for Portugal and Spain

- 5. Historians Dispute His First Few Voyages

- 6. Amerigo Suggested It Being a New World on a Voyage to Brazil

- 7. He Returned to Spain and Consulted the King

- 8. He became a Significant Figure in the Infrastructure of Spanish Exploration

- 9. He Died in 1512

- 10. He Became The Most Controversial Figure of the Age of Exploration

Unlike other Spanish explorers, he was not a conqueror or even a military man. He knew geography, astronomy, and eventually navigation, which allowed him to notice different surroundings that may not have been familiar to others.

1. Amerigo Vespucci was Born to an Affluent Italian Family

Earlier generations of Vespucci had funded a family chapel in the Ognissanti church, and the nearby Hospital of San Giovanni di Dio was founded by Simone di Piero Vespucci in 1380.

Vespucci's immediate family was not especially prosperous, but they were politically well-connected.

Amerigo's grandfather, also named Amerigo Vespucci, served a total of 36 years as the chancellor of the Florentine government, known as the Signoria, and Nastagio also served in the Signoria and in other guild offices.

Also Read: Amerigo Vespucci Timeline of Discoveries and Accomplishments

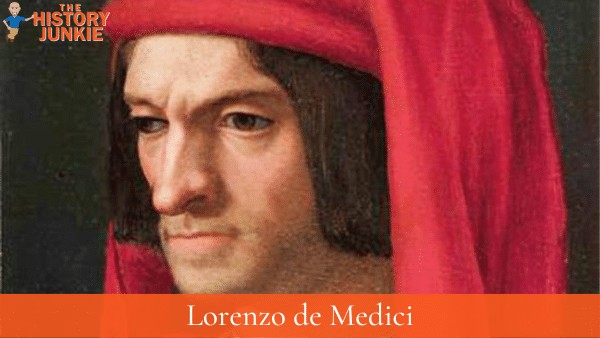

More importantly, the Vespuccis had good relations with Lorenzo de Medici, the powerful de facto ruler of Florence.

These connections played a significant role in the opportunities available to Amerigo and his younger brothers.

They may not have been as wealthy as some, but they lived a comfortable life, unlike many during that time period.

2. He was Educated by His Uncle

The older brothers of Amerigo went to the University of Pisa, but he was tutored by his uncle.

It may seem that being tutored by his uncle was not as great of an opportunity as his older brothers. However, his uncle was one of the best humanist thinkers in Florence at the time, and the education he gave Amerigo would play a significant role in his future accomplishments.

Amerigo's later writings demonstrated a familiarity with the work of the classic Greek cosmographers Ptolemy and Strabo and the more recent work of Florentine astronomer Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli.

This was a direct influence of his uncle, as he would have referenced these writings.

3. He Worked for the Medici Family

The Vespucci family was well-connected to the Medici family, and as Amerigo grew up, he would find himself working for the Medicis and securing their investments.

This work would result in meeting many connections.

One specific connection would be a man with the surname Berardi. Berardi had connections to Christopher Columbus.

This would be the connection that would eventually bring him into the mariner career.

4. He Sailed for Portugal and Spain

The explorers of that time were usually bound to the crown that funded their voyage. If they switched monarchs, then it was usually a problem, but this was not true for Amerigo Vespucci.

He originally sailed to the Bahamas under the Spanish flag.

His next voyages took place at the beginning of the 16th century, and he sailed on two voyages under the Portuguese flag.

After sailing for Portugal, he returned to Spain and sailed under the Spanish flag again. The Spanish monarch did not seem to mind the conflict and was only concerned about finding a quicker passage to Asia.

5. Historians Dispute His First Few Voyages

The evidence for Vespucci's voyages of exploration is limited to a few letters that he wrote or that were attributed to him. Historians have disagreed about the authorship, accuracy, and truthfulness of these documents.

As a result, there is much debate about the number of voyages that Vespucci took, their routes, and his accomplishments.

Starting in the late 1490s, Vespucci participated in two voyages to the New World that are relatively well-documented. However there is also evidence for two other voyages, but the evidence for these voyages is more problematic.

Traditionally, Vespucci's voyages are referred to as the "first" through "fourth," even by historians who do not believe that all four voyages took place.

In conclusion, the evidence for Vespucci's voyages is limited and controversial. It is likely that he took two voyages to the New World, but it is also possible that he took more or fewer voyages.

The exact routes that he took and his accomplishments are also uncertain.

6. Amerigo Suggested It Being a New World on a Voyage to Brazil

As stated previously, Amerigo Vespucci received a broad education from his uncle. He was familiar with the geography of Asia, so when he was sailing under the Portuguese flag on orders from King Manuel, I to research the large land mass that was found during a voyage by Pedro Alvares Cabral.

Upon seeing the mass and mapping it out, it became clear that the mass they were looking at did not fit what was known about Asia and that they were possibly looking at a different continent.

Obviously, his thoughts became true, and South America and North America would bear his name.

7. He Returned to Spain and Consulted the King

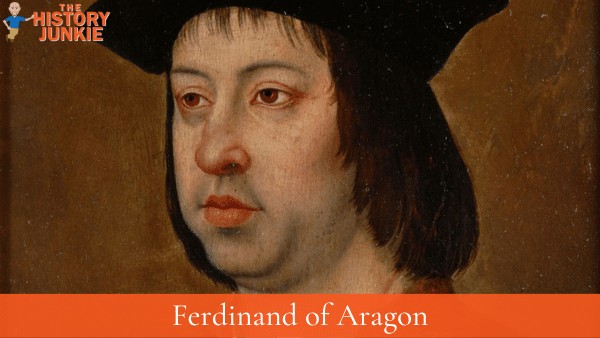

By early 1505, Vespucci was back in Seville. His reputation as an explorer and navigator continued to grow, and his recent service in Portugal did not seem to damage his standing with King Ferdinand.

On the contrary, the king was likely interested in learning about the possibility of a Western passage to India.

In February, he was summoned by the king to consult on matters of navigation. During the next few months, he received payments from the crown for his services, and in April, he was declared by royal proclamation a citizen of Castile and León.

8. He became a Significant Figure in the Infrastructure of Spanish Exploration

From 1505 until his death in 1512, Vespucci remained in service to the Spanish crown. He continued his work as a chandler, supplying ships bound for the Indies.

In March 1508, he was named chief pilot for the Casa de Contratación or House of Commerce, which served as a central trading house for Spain's overseas possessions.

Also Read: Famous Spanish Explorers

He was paid an annual salary of 50,000 maravedis with an extra 25,000 for expenses.

In his new role, Vespucci was responsible for ensuring that ships' pilots were adequately trained and licensed before sailing to the New World.

He was also charged with compiling a "model map" based on input from pilots who were obligated to share what they learned after each voyage.

9. He Died in 1512

Amerigo Vespucci died in 1512 and left his modest estate to his wife.

His wife received an annual pension and was taken care of for the rest of her life.

He had risen from the most unlikely brother to become something in his family to the Master Navigator of Spain and held more influence than anyone in the country as to how the New World was perceived.

Also Read: Famous Spanish Conquistadors

He was not a rich man as many of the Spanish Conquistadors would become, but he made a good living, and his ideas of how the world physically looked were built on in later generations.

10. He Became The Most Controversial Figure of the Age of Exploration

Vespucci has been called "the most enigmatic and controversial figure in early American history." The debate has become known among historians as the "Vespucci question."

How many voyages did he make? What was his role on the voyages, and what did he learn? The evidence relies almost entirely on a handful of letters attributed to him.

Many historians have analyzed these documents and have arrived at contradictory conclusions.

In 1515, Sebastian Cabot became one of the first to question Vespucci's accomplishments and express doubts about his 1497 voyage. Later, Bartolomé de las Casas argued that Vespucci was a liar and stole the credit that was due to Columbus.

By 1600, most regarded Vespucci as an impostor and not worthy of his honors and fame. In 1839, Alexander von Humboldt, after careful consideration, asserted the 1497 voyage was impossible but accepted the two Portuguese-sponsored voyages.

Humboldt also called into question the assertion that Vespucci recognized that he had encountered a new continent. According to Humboldt, Vespucci (and Columbus) died in the belief that they had reached the eastern edge of Asia.

Vespucci's reputation was perhaps at its lowest in 1856 when Ralph Waldo Emerson called Vespucci a "thief" and "pickle dealer" from Seville who managed to get "half the world baptized with his dishonest name."

Opinions began to shift somewhat after 1857 when Brazilian historian Francisco Adolfo de Varnhagen wrote that everything in the Soderini letter was true. Other historians followed in support of Vespucci, including John Fiske and Henry Harrisse.

In 1924, Alberto Magnaghi published the results of his exhaustive review of Vespucci's writings and relevant cartography. He denied Vespucci's authorship of the 1503 Mundus Novus and the 1505 Letter to Soderini, the only two texts published during his lifetime.

He suggested that the Soderini letter was not written by Vespucci but was cobbled together by unscrupulous Florentine publishers who combined several accounts – some from Vespucci, others from elsewhere.

Magnaghi determined that the manuscript letters were authentic, and based on them, he was the first to propose that only the second and third voyages were true and the first and fourth voyages (only found in the Soderini letter) were fabrications.

While Magnaghi was one of the chief proponents of a two-voyage narrative, Roberto Levellier was an influential Argentinian historian who endorsed the authenticity of all of Vespucci's letters and proposed the most extensive itinerary for his four voyages.

Other modern historians and popular writers have taken varying positions on Vespucci's letters and voyages, espousing two, three, or four voyages and supporting or denying the authenticity of his two printed letters.

Most authors believe that the three manuscript letters are authentic, while the first voyage, as described in the Soderini letter, draws the most criticism and disbelief.

A two-voyage thesis was accepted and popularized by Frederick J. Pohl (1944) and rejected by Germán Arciniegas (1955), who posited that all four voyages were truthful. Luciano Formisiano (1992) also rejects the Magnaghi thesis (acknowledging that publishers probably tampered with Vespucci's writings) and declares all four voyages genuine but differs from Arciniegas in details (particularly the first voyage).

Samuel Morison (1974) flatly rejected the first voyage but was noncommittal about the two published letters. Felipe Fernández-Armesto (2007) calls the authenticity question "inconclusive" and hypothesizes that the first voyage was probably another version of the second; the third is unassailable, and the fourth is probably true. (Wikipedia)

While other explorers and conquistadors may be controversial, there are none more debated on the validity of their claims than Amerigo Vespucci.