Anne Hutchinson was a Puritan, a mother of 15, and an important participant in the Antinomian Controversy, which caused much disruption in the Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638.

Her strong religious convictions were at odds with the established Puritan clergy in the Boston area, and her popularity and charisma helped create a theological divide that threatened to destroy the Puritans' religious community in New England.

She was eventually tried and convicted, then banished from the colony with many of her supporters.

Jump to:

Her Father's Influence

Anne Hutchinson was born Anne Marbury in Alford, Lincolnshire, England, and was baptized there on 20 July 1591, the daughter of Francis Marbury and Bridget Dryden.

Anne's father had a profound impact on her childhood.

Her father worked within the clergy of the Anglican Church of England and, before she was born, had a falling out with them. He was censured and was put under house arrest.

During his house arrest, he wrote a transcript of the trial and used it to educate his children, including Anne.

The Marburys lived in Alford for the first 15 years of Anne's life, and she received a better education than most girls of her time, with her father's strong commitment to learning, and she also became intimately familiar with scripture and Christian tenets.

Despite his early years, Anne's father became a successful Puritan minister. At the high point in his career, he died suddenly at 55 years old. Anne was 19. He was known as one of the great Puritan Preachers of his day and even drew adoration from Sir Francis Bacon.

Young Adult Years

Anne married William Hutchinson, a fabric merchant.

During the couple's early years, they were drawn to popular Puritan ministers (John Cotton and John Wheelwright) who preached a different doctrine.

While he held true to all the core doctrines of the Bible, he emphasized absolute grace and downplayed works. His focus on grace influenced much of Anne's thinking about religious practices.

She began to see that faith in Christ gave her more freedom than she had been taught. This led to her questioning the Puritanical doctrine of works.

John Cotton drew the attention of the Archbishop and then went into hiding. Eventually, he ended up seeking refuge in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. His departure caused Anne much distress.

The Hutchinson's made plans to follow Cotton. Anne was far along in her 14th pregnancy, so she and her husband waited to make the journey. However, they sent their oldest son, Edward, with Cotton to New England.

In 1634, 43-year-old Anne Hutchinson set sail from England with her 48-year-old husband William and their other ten surviving children, aged about eight months to 19 years.

The Hutchinsons quickly became leading members in Boston. William had one of the largest houses in the area built and became a town selectman and a deputy to the general court.

Anne settled into her new home and used their residence to take care of the ill. She was a practicing midwife and helped care for those in childbirth.

She also provided spiritual guidance to many of the women. She drew much positive attention from John Winthrop, who spoke highly of her spiritual mindset.

Hutchinson's visits to women in childbirth led to discussions along the lines of the conventicles in England. She soon began hosting weekly meetings at her home for women who wanted to discuss Cotton's sermons and hear her explanations and elaborations.

Her meetings for women became so popular that she had to organize meetings for men, as well, and she was hosting 60 or more people per week. These gatherings brought women, as well as their husbands.

Hutchinson's meetings began to grow in popularity. Her theological interpretations began diverging from the more legalistic views found among the colony's ministers, and the attendance increased at her meetings and soon included Governor Vane.

Her ideas that one's outward behavior was not necessarily tied to the state of one's soul became attractive to those who might have been more attached to their professions than to their religious state, such as merchants and craftsmen.

The Puritans began to argue that her meetings were confusing the faithful, to which Hutchinson quipped back with an excellent verse in Titus that said it was the responsibility of the older women to teach the younger women.

Puritan minister John Wilson returned from a lengthy trip to England and resumed his preaching. This was the first time that Anne had been exposed to his teaching, to which she found herself in disagreement.

She and her followers began to disrespect the minister during church and found excuses to leave when he preached. This was the first public sign of dissension.

Dissension and Banishment

Dissensions continued, and many Puritans began to push back on John Cotton and Hutchinson's teachings. The arrival of John Wheelwright only caused further disruption as the Puritan minister identified with John Cotton's teachings of grace over the Puritan's emphasis on morality.

Wheelwright began preaching at a church 10 miles outside of Boston. The sermons drew more attention, as did the continued lack of respect for the Reverend John Wilson. Finally, John Winthrop was alerted, and he gave a stern warning to the dissenters.

The controversy would dominate John Winthrop's life for the next two years. He viewed Hutchinson as having brought over two beliefs that were problematic: the first being that the Holy Spirit could live within a person and the second that no sanctification could help our evidence of justification. Both of these beliefs had a foundation in the doctrine of God's Grace.

The Puritan ministers held a conference at the house of John Cotton to which the Hutchinsons were invited. They discussed their dissensions. During this discussion, Hutchinson only spoke when spoken to and addressed one or two ministers at a time.

By late 1636, as the controversy deepened, Hutchinson and her supporters were accused of two heresies in the Puritan church: antinomianism and familism. Antinomianism meant that if one was under the law of grace, the moral law did not apply, allowing one to engage in immoral acts.

Familism was named for a 16th-century sect called the Family of Love, and it involved one's perfect union with God under the Holy Spirit, coupled with freedom both from sin and from the responsibility for it.

Hutchinson's dissenters began accusing her and her followers of practicing free love, which Hutchinson was opposed.

Hutchinson, Wheelwright, and Vane all took leading roles as antagonists of the orthodox party, but theologically, it was Cotton's differences of opinion with the colony's other ministers that were at the center of the controversy

By winter, the theological schism had become great enough that the General Court called for a day of fasting to help ease the colony's difficulties. During the appointed fast day on Thursday, 19 January 1637, Wheelwright preached at the Boston church in the afternoon. To the Puritan clergy, his sermon was "censurable and incited mischief."

The colony's ministers were offended by the sermon, but the free grace advocates were encouraged. Governor Vane began challenging the doctrines of the clergy, and supporters of Hutchinson refused to serve against the Pequot tribe during the Pequot War of 1637 because Wilson was the chaplain of the expedition.

Wheelwright and Vane were replaced. Wheelwright was put on trial for his sermon and found guilty.

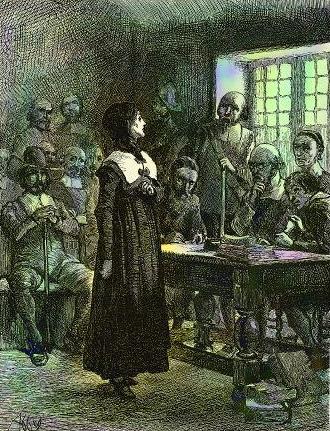

Anne Hutchinson on Trial

The snowball continued, and finally, on 7 November 1637, Anne Hutchinson was put on trial. Her close ally, Governor Charles Vane, had been replaced by John Winthrop, who presided over the trial.

On the first day of the trial, John Winthrop found it difficult to pin anything onto Anne. She effectively stonewalled him at every turn, and since she had never spoken her opinion in a public setting (the meetings were held in the privacy of her home), the prosecution did not have the evidence to convict her on anything.

Thomas Dudley began his prosecution of Anne. She again gave excellent responses to his charges. He was unable to pin anything on her. However, he began to build his case against her by using the private statements she gave in the meeting with other ministers at the house of John Cotton prior to the trial.

Anne argued that her statements to the ministers were in response to their questions and that it was a private meeting. She quoted Proverbs 29:25 in her defense, which differentiated between public and private speech. The court was not interested in that logic.

During the morning of the second day of the trial, it appeared that Hutchinson had been given some legal counsel the previous evening, and she had more to say. She continued to criticise the ministers for violating their mandate of confidentiality. She said that they had deceived the court by not telling about her reluctance to share her thoughts with them. She insisted that the ministers testify under oath, which they were very hesitant to do.

Magistrate Simon Bradstreet said that "she would make the ministers sin if they said something mistaken under oath," but she answered that if they were going to accuse her, "I desire it may be upon oath." As a matter of due process, the ministers would have to be sworn in but would agree to do so only if the defense witnesses spoke first.

John Cotton was put on the stand and questioned. When Cotton testified, he tended to not remember many events of the October meeting and attempted to soften the meaning of statements that Hutchinson was being accused of. He stressed that the ministers were not as upset about any Hutchinson remarks at the end of the October meeting as they appeared to be later.

Hutchinson then spoke and said the following: "You have no power over my body, neither can you do me any harm, for I am in the hands of the eternal Jehovah, my Saviour, I am at his appointment, the bounds of my habitation are cast in heaven, no further do I esteem of any mortal man than creatures in his hand, I fear none but the great Jehovah, which hath foretold me of these things, and I do verily believe that he will deliver me out of our hands. Therefore, take heed how you proceed against me, for I know that for this you go about to do to me, God will ruin you and your posterity and this whole state."

This statement was consistent with her character but put a dagger in her trial. Cotton was questioned if he agreed with the statements of Hutchinson, to which he did not. He was still upset with the aggression the church was taking over members of his congregation, but Winthrop did not want to quibble over what he believed to be insignificant details.

The court seemed to be ready to convict Anne. However, William Coddington stood in her defense and said, "I do not see any clear witness against her, and you know it is a rule of the court that no man may be a judge and an accuser too," ending with, "Here is no law of God that she hath broken nor any law of the country that she hath broke, and therefore deserve no censure."

She was convicted and banished for being a heretic. Soon after, she was removed from the Congregation when her mentor, John Cotton, argued against her. She and her followers were given three months to leave.

Rhode Island and New Netherland

William Hutchinson, along with William Coddington, began plans to move from the colony. After looking into settling various areas, they were convinced by Roger Williams to come to Providence Plantations.

Hutchinson, her children, and others accompanying her traveled for more than six days by foot in the April snow to get from Boston to Roger Williams' settlement at Providence. They took boats to get to Aquidneck Island, where many men had gone ahead of them to begin constructing houses.

There was a rift in the new settlement that led to William Coddington moving and forming a new colony called Portsmouth. They adopted a new government which provided for trial by jury and separation of church and state

Hutchinson's husband William died sometime after June 1641 at the age of 55, the same age at which Anne's father had died. He was buried in Portsmouth.

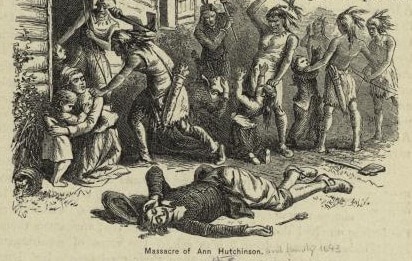

Due to threats from the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Hutchinson moved her family to New Netherland and into the jurisdiction of the Dutch. They settled in an area that was inhabited by the Native Americans.

The Hutchinsons were killed in a massacre. All, except Anne's daughter Susanna, died in the raid.