On the night of 20 October 1861, Union Brigadier General Charles P. Stone put into action a plan to attack what had been reported as a small, unguarded Confederate camp between the Potomac River at Ball's Bluff near Leesburg, Virginia.

Later, after Stone learned there was no camp, he allowed the operation to continue, now modified to capture Leesburg itself.

However, a lack of adequate communication between commanders, problems with logistics, and violations of the principles of war hampered the operation.

What originally was to be a small raid instead turned into a military disaster called the Battle of Ball's Bluff, resulting in the death of a popular U.S. senator, the arrest and imprisonment of General Stone, and the creation of a congressional oversight committee that would keep senior Union commanders looking over their shoulders for the remainder of the war.

Before the Battle

On 22 July 1861, the day after the Union defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run, President Abraham Lincoln summoned 35-year-old Major General George B. McClellan to Washington and assigned him command of all troops in the Washington area. McClellan's recent military victories in western Virginia had thrust him into the limelight and brought public acclaim.

Lincoln believed McClellan could restore the morale of the beaten Union Army and rebuild it for future operations. McClellan immediately began the complex task of organizing and training a large force capable of defeating the Southern army in Virginia.

A month after being assigned command, he designated his force the Army of the Potomac and molded it into a formidable fighting machine, more than 100,000 men strong.

On the other side of the Potomac River, the Confederate Army, commanded by General Joseph E. Johnston, numbered about 40,000. After the Confederate victory at Manassas, Johnston contemplated going on the offensive, crossing into Maryland, and threatening either Washington or Baltimore.

However, Johnston felt his offensive would require no less than 60,000 men and requested reinforcements from Richmond. In late September, the Confederate government advised Johnston that it would be unable to provide additional troops. The Confederate commander was forced to go on the defensive and reluctantly began to withdraw his army from the vicinity of Washington.

By mid-October, the main part of the Confederate Army was at Centreville, where Johnston took up a defensive line and prepared winter quarters.

Near Leesburg, Johnston left a single brigade to guard the narrow river crossings north of Washington and to provide a line of communications between Confederate forces at Winchester and those at Manassas.

In Washington, McClellan had organized his Army of the Potomac into eleven divisions and began posting them to protect the capital. Aware that Johnston had troops at Leesburg, he became concerned that the Confederates might attempt to cross the Potomac above Washington.

To guard against such a move, the 6,500-man division of Brig. Gen. Charles P. Stone, known as the Corps of Observation, was encamped near Poolesville, Maryland, to watch the several fords and ferries to the east of Leesburg.

Stone's division consisted of three infantry brigades. Brig. Gen. Willis A. Gorman's brigade included the 2d New York State Militia (later redesignated the 82d New York Infantry), 1st Minnesota Infantry, 15th Massachusetts Infantry, and 34th and 42d New York Infantries.

The brigade of Brig. Gen. Frederick W. Lander contained the 19th and 20th Massachusetts Infantries, the 7th Michigan Infantry, and one company of Massachusetts sharpshooters. Colonel (and U.S. senator) Edward D. Baker commanded what was known as the California brigade: the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th California Infantries.

These regiments had been recruited mostly in Pennsylvania, and after the Battle of Ball's Bluff and the protest of the Pennsylvania governor, the regiments were redesignated the 71st, 69th, 72d, and 106th Pennsylvania Infantries, respectively.

Stone's division also included six companies of the 3d New York Cavalry, a detachment of Maryland cavalry known as the Putnam Rangers (later redesignated Company L, 1st Maryland Cavalry), and three batteries of artillery: Battery I, 1st U.S. Artillery; Battery B, 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery; and Battery K, 9th New York State Militia (later redesignated 6th New York Independent Battery).

To guard crossing sites farther north, the division of Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks, headquartered at Darnestown, Maryland, established pickets at the mouth of the Monocacy River and some miles northward. About twenty-three miles southeast of Leesburg, the division of Brig. Gen. George A. McCall was encamped just below the Potomac at Langley, Virginia.

Opposite Stone's Corps of Observation, on the Virginia side of the river, was the 7th Brigade of Col. Nathan G. Evans. Evans' command consisted of the 13th, 17th, and 18th Mississippi Infantries; 8th Virginia Infantry; Companies B, C, and E. 4th Virginia Cavalry, and Company K, 6th Virginia Cavalry; and the 1st Company, Richmond Howitzers, a total force of about 1,700 men.

About two miles east of the town, Evans had an earthen fort constructed, named it Fort Evans, and established his headquarters there.

During October, Evans' brigade was covering a seven-mile distance of the Potomac River east of Leesburg. Along this stretch, Evans' pickets guarded crossing sites, including Conrad's Ferry (known today as White's Ferry), Smart's Mill, and Edwards' Ferry.

About halfway between Conrad's and Edwards' Ferries is Ball's Bluff, named for the local Ball family. Rising 100 feet above the river, covered by trees and rock outcroppings, the bluffs overlook Harrison's Island. Harrison's Island itself is flat and, at the time of the battle, was about 350 yards wide and 3 miles in length.

On the Maryland side of the island, the Potomac River was about 250 yards wide, but on the Virginia side, it was only 60 to 80 yards wide.

Along the Maryland shore, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal transported barges between Cumberland, Maryland, and Georgetown, D.C. General Stone maintained pickets on Harrison's Island and had small entrenchments thrown up to protect the men from any Confederate fire from the Virginia bluffs.

Through the end of summer and early fall of 1861, the opposing pickets along the river fell into the daily practice of watching the crossing sites. Although fraternization between Confederate and Union pickets was forbidden, the soldiers sometimes traded newspapers, tobacco, or other items by making small rafts and allowing them to drift across to the other side.

Or when the river was low, they might wade out into the center of the water and engage in conversation with one another. Occasionally, there would be shots exchanged, but generally, the duty was routine and dull.

In mid-October, after receiving reports that the Confederate Army had fallen back to Centreville and Manassas, McClellan saw an opportunity to secure the river-crossing sites north of Washington and perhaps occupy Leesburg. He hoped that a show of force would cause Evans' Confederates to abandon the town without a fight, giving McClellan an easy victory and satisfying a Congress anxious for the Union Army to take the initiative.

On 19 October, McClellan ordered General McCall to march his division from Langley to Dranesville, about fourteen miles south of Leesburg.

This movement was not only meant to intimidate Evans into withdrawing from Leesburg but was an opportunity to learn the position of the Confederates and allow Army topographical engineers to prepare maps of the area. Once his mission was completed, McCall was to return to Langley the following day.

By midnight on the nineteenth, Evans was alerted to McCall's advance when a Union courier carrying instructions to McCall's command was captured. Instead of evacuating the area, Evans moved his brigade to a defensive position on the Leesburg Turnpike and along the north side of Goose Creek.

The following morning, 20 October, a Union signal station at Sugar Loaf Mountain, now unable to see Evans 'force, reported to McClellan that the enemy had apparently moved away from Leesburg.

McClellan, unsure whether the Confederates had actually evacuated the town, decided to apply additional pressure on General Stone's division. He sent a message to Stone saying McCall's division had advanced to Dranesville and told Stone to keep a lookout toward Leesburg to see if McCall's movement would drive the Confederates away.

McClellan ended the communique with, "Perhaps a slight demonstration on your part would have the effect to move them." McClellan failed to tell Stone that the movement of McCall's division to Dranesville was only temporary and that McCall would return to Langley the following day.

He also neglected to explain to Stone that the "slight demonstration" was expected to be no more than a show of force on the Maryland shore and that no troops were expected to cross the river for the purpose of fighting.

On the afternoon of 20 October, Stone moved a portion of General Gorman's brigade, consisting of the 2nd New York State Militia and 1st Minnesota Infantry, to Edwards' Ferry for the demonstration. Gorman's 34th New York Infantry was at Seneca, Maryland, eight miles downstream.

Gorman's 42d New York Infantry was ordered to the vicinity of Conrad's Ferry, while the 15th Massachusetts Infantry remained on picket duty in the vicinity of Harrison's Island along with General Lander's 19th and 20th Massachusetts Infantries.

The movement of Gorman's units to the ferry was joined by the 7th Michigan Infantry of Lander's brigade, along with the Putnam Rangers and two companies of the 3rd New York Cavalry.

At the ferry, General Gorman had three flatboats removed from the canal and placed in the river preparatory to a crossing. As Union artillery fire drove the Confederates from view and while the remainder of his command waited on the Maryland shore, Gorman began crossing only two companies of the 1st Minnesota Infantry.

While the Confederates were being distracted by the demonstration at Edwards' Ferry, Stone ordered Col. Charles P. Devens, 15th Massachusetts Infantry, to send 38-year-old Capt. Chase Philbrick of Company H and twenty men on a scouting expedition toward Leesburg via Ball's Bluff.

To support the reconnaissance and protect the group's return, Colonel Devens was also ordered to cross to Harrison's Island four companies of his regiment, Companies A, C, G, and I, where they would join the remainder of Company H already there on picket duty.

Stone anticipated that Philbrick would depart in time to accomplish his mission at the same time as the Edwards' Ferry demonstration concluded. However, due to a delay in delivering the order to Philbrick, the scouting party did not cross the river until just before dark, after which it climbed to the bluff and cautiously followed a path through the woods.

With the approach of darkness, Stone ended his demonstration at Edwards' Ferry and withdrew the Minnesota troops to the Maryland shore. At this point, Stone had successfully carried out McClellan's suggestion for a slight demonstration, and he informed McClellan of the temporary crossing and of the scouting party still near Leesburg.

The Battle

Meanwhile, Philbrick's scouting party had walked in the dark less than a mile from the bluffs when it spotted what appeared to be a row of about thirty tents silhouetted along a ridgeline near the home of the Jackson family. Although no Confederates could be seen, Philbrick and his group fell back to the bluff, crossed back into Maryland, and about 2200 informed Stone of the discovery of the unguarded camp. Seeing an opportunity for a quick raid, Stone decided to send a force across the river to destroy the camp.

Although General McClellan had not ordered such a river crossing in the Leesburg area, Stone was acting with proper authority. Two months earlier, McClellan had instructed Stone that "should you see the opportunity of capturing or dispersing any small party by crossing the river, you are at liberty to do so, though great discretion is recommended in making such a movement." In Stone's words, this was "precisely one of those pieces of carelessness on the part of the enemy that ought to be taken advantage of."

He quickly wrote orders for Colonel Devens to take five companies of the 15th Massachusetts Infantry across the river with silence and rapidity to destroy the camp.

To cover the return of Devens' force, Col. William R. Lee, commanding the 20th Massachusetts Infantry, was ordered to cross his regiment to Harrison's Island and to send two companies across the river to the bluff.

Stone also ordered the 2nd New York State Militia at Edwards' Ferry to send eight men along with two 12-pounder mountain howitzers up the canal towpath to a point opposite Harrison's Island. Second Lt. Frank S. French, Battery 1, 1st U.S. Artillery, was assigned to command the guns and four men of Battery I were assigned to the crews. These guns would be under the overall control of Colonel Lee and could fire onto Ball's Bluff to protect a hasty withdrawal.

Artillery from Battery B, 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery, would also be placed in support, with four 12-pounder rifled guns being ordered to the canal towpath near the island. The other two guns of the battery would remain north of Conrad's Ferry, near the mouth of the Monocacy River 11 And finally, Stone ordered the 1st California Infantry, commanded by Lt. Col. Isaac J. Wistar, and the 42d New York Infantry, commanded by Col. Milton Cogswell, to wait at Conrad's Ferry, ready to provide additional support if needed.

In addition to attacking the Confederate camp, Devens' orders stated that after accomplishing his mission, he was to return to the Maryland shore unless a strong position was found on the Virginia side of the river that could be held until reinforcements arrived. He was then to hold on and report.

About midnight on 20 October, Devens and Companies A, C, G, H, and I (about 300 men) quietly moved to the crossing site on the western side of Harrison's Island. Despite the cold, Devens ordered his men to march without overcoats or knapsacks, explaining that they might be cold for two or three hours in the early morning, but during the day, they would be warm enough. There were only two boats available for the crossing: a lifeboat that could hold twenty-five men and a skiff capable of carrying less than ten men.

To increase the number of men crossing, another skiff was brought across the island from the Maryland side and placed in the river. After much difficulty, the crossing was completed at about 0400 on 21 October.

Once on the Virginia shore, the companies followed the riverbank southward about seventy yards and climbed a narrow, steep path to the top. When the last group had climbed the bluff, Colonel Devens crossed over, briefly getting lost in the dark along the riverbank before finding the path to the top.

After checking on his men, Devens returned to the riverbank to make sure the two companies of the 20th Massachusetts Infantry could find their way to the top of the bluff.12 Colonel Lee had chosen Companies D and I of the 20th to make the crossing and accompanied them himself, leaving the remaining five companies on the island under the command of Major Paul Revere, grandson of the Revolutionary War hero.

Empty camp

At first light, shortly before 0600, Devens led his men down a narrow path and into the woods beyond, leaving Lee and his companies on the bluff. With Philbrick's Company H in the lead, Devens' force soon reached the ridge where the enemy camp had been seen the night before. However, on reaching the site, Devens discovered that Philbrick had been deceived.

A row of trees on the ridgeline running perpendicular to the path, with the night sky showing through the openings between the trees, had presented only the appearance of a row of tents. With no camp to attack, Devens decided to salvage something from the mission.

While the rest of his command waited in the woods, Devens, Philbrick, and 1st Lt. Church Howe, the regimental quartermaster, crossed over the ridge and scouted toward the town. After a short while, they returned, having seen no enemy troops and only a few distant tents.

Devens then decided to exercise the discretion allowed in his orders and not return to the bluff. About 0700, he sent Lieutenant Howe to Stone to report that there was no enemy camp, and Devens would hold his position and await further orders.

To distract Confederate attention from Devens' movement, Stone had earlier ordered General Gorman to make a second crossing at Edwards' Ferry. Under cover of artillery fire, two companies of the 1st Minnesota Infantry and a detachment of about thirty horsemen of the 3rd New York Cavalry would cross over to the Virginia shore.

While infantry covered the crossing site, the cavalry would advance as far as the Leesburg Turnpike and report on the number and disposition of any enemy seen.

Back at the bluff, as the sky grew lighter, Colonel Lee took a quick look at his surroundings. His troops were on the edge of an open field, trapezoidal in shape. Woods surrounded the field on all sides, and the path leading toward Leesburg crossed the field and entered the woods almost four hundred yards away.

Lee sent out pickets to check the woods to the north and south of the field and continued to await the results of Devens' operation. At about 0730, several enlisted men of Company I, 20th Massachusetts Infantry, in the woods to picket the slope above a ravine north of the open field, were fired upon.

On the opposite slope, pickets of Company K, 17th Mississippi Infantry, south of Smart's Mill, had seen the group coming and opened fire, wounding a sergeant and sending the Massachusetts men scurrying back up the slope.

The Confederate pickets quickly informed their commander, Capt. William L. Duff, of the Union Crossing. Duff forwarded the news to Evans, then marched from his camp at Big Spring less than a mile away with the remaining forty men of his company, following a long ravine to the top of the ridge near the Jackson house.

Devens' pickets spotted Duff and his men at about 0800 and alerted Devens. Captain Philbrick was ordered to advance Company H over the ridge and confront the Confederates, while Capt. John Rockwood, with his Company A, moved to the right to block the road to Smart's Mill and prevent the enemy from escaping to the north.

Surprised by the sudden appearance of Union soldiers and outnumbered, Duff and his men quickly fell back about 300 yards down the slope, closely followed by Philbrick's company. As Philbrick's unit drew closer, Duff ordered his men to take aim while repeatedly calling on the Union troops to halt.

Philbrick's men called out that they were "friends," but when the two companies were less than a hundred yards apart, Duff gave the command "fire," knocking down several of the Massachusetts men and opening a lively skirmish. Devens was about to order Company G to Philbrick's aid when he was warned of the approach of Confederate cavalry from the direction of Leesburg.

Lt. Col. Walter H. Jenifer, commanding four companies of Virginia cavalry, had been camped nearby and heard of the Union crossing at Ball's Bluff. With Companies B, C, and E, 4th Virginia Cavalry, and Company K, 6th Virginia Cavalry, Jenifer hurried to support Duff's command.

Devens ordered Philbrick and Rockwood to fall back. After waiting a few minutes on the east side of the ridge and unsure of the size of the Confederate force on the other side, Devens marched his command back to the bluff. Duff also fell back another 300 yards, where he was joined by Jenifer's cavalry. In the short skirmish, Philbrick had lost one killed, nine wounded, and two missing. Duff's casualties were three wounded, one seriously.

Both Duff's and Jenifer's commands searched the site of the skirmish, gathering dropped weapons and making prisoners of several of the Union wounded. Later, an order arrived for Jenifer to report to Fort Evans, so he and his cavalry departed.

Back at the bluff, Colonel Lee had heard the firing to the front. Expecting Devens' command to be returning shortly, Lee placed Company D on the left side of the path and Company I on the right side. At about 0830, Devens and his men appeared and halted on the path in front of Lee's command.

Devens, according to Lee, seemed angry at the result of the operation. When Lee suggested to Devens that he form his men into a line of battle instead of them standing in column on the path, Devens did not respond.

After remaining about half an hour, Devens, without saying a word to Lee, marched back up the path and out of sight. Arriving at his earlier position in the woods near the Jackson house, Devens waited for orders from Stone.

Meanwhile, at Edwards' Ferry, two companies of Minnesota troops began crossing the river, along with about thirty horsemen of the 3rd New York Cavalry. While the infantry guarded the crossing site, the cavalry scouted toward the Leesburg Turnpike, where it had a brief encounter with the 13th Mississippi Infantry before returning to the ferry.

Watching the Edwards' Ferry operation from the Maryland shore, General Stone received Devens' report at about 0830 on the error regarding the Confederate camp.

Unaware of Devens' morning skirmish, Stone informed McClellan that Devens had crossed the river and had proceeded to within a mile and a half of Leesburg without seeing any enemy and that Stone's cavalry had briefly skirmished with Confederates at Edwards' Ferry. McClellan responded with, "I congratulate your command. Keep me constantly informed."

Shortly after Devens had returned to the vicinity of the Jackson house, Lieutenant Howe arrived with orders from Stone. Devens was to remain where he was, and a detachment of cavalry would arrive for the purpose of scouting toward the town.

Howe also said that the remaining five companies of the 15th Massachusetts Infantry under Lt. Col. George H. Ward would be crossing over to the Virginia shore and marching to Smart's Mill on Devens' right flank. After expressing concern that Ward should join him at the front rather than going to Smart's Mill, Devens sent the quartermaster back to Edwards' Ferry with word of the morning skirmish.

On the way back, Howe met Ward preparing to cross and told him of the morning skirmish and Devens' desire that Ward support him as soon as possible.

Ward sent word to Stone that instead of marching to Smart's Mill, Ward would join Devens' command. Ward then crossed the river and marched directly up the same path Devens had followed. By 1100, all ten companies had united, giving Devens a force of about 650 men.

In the meantime, about ten cavalrymen, led by a noncommissioned officer and sent by Stone to scout for Devens, crossed the river from Maryland and arrived on the Virginia riverbank. Accompanying them was Capt. Charles Candy of General Lander's staff, temporarily acting as an aide to General Stone.

While the cavalrymen waited below, Candy rode to the top of the bluff, where he met with Colonel Lee. After writing down Lee's evaluation of the general situation, Candy returned to the riverbank and crossed back to the Maryland shore. For unexplained reasons, the cavalrymen, instead of reporting to Devens, followed Candy back across the river.

Thus, Devens and later Baker were deprived of a means of obtaining advance information about the approach of any Confederate force.

Soon after Devens had returned to the Jackson house, Colonel Lee sent a note to Major Revere on the island, telling him that Devens had encountered the enemy and that "we are determined to fight." This prompted Revere to begin crossing his five companies of the 20th Massachusetts Infantry to the Virginia shore, a move that by noon would increase Lee's force to 317 men.

Lee had also stopped Lieutenant Howe as he passed by on one of his trips to and from Edwards' Ferry. In response to a question from Howe regarding Lee's assessment of the situation, Lee said to tell Stone that "if he wished to open a campaign in Virginia, now was the time."

Lee posted his seven companies, A, C, D, E, G, H, and I, along the bluff. The men were placed in a line parallel with the eastern edge of the open field, with their backs to the river, behind a slight rise of ground, and just in front of the wood line.

Company D was thrown out as skirmishers in the woods on the left, while Company H was placed in the woods on the right. Revere's troops, with difficulty, had also brought the two mountain howitzers.

The guns were hauled up the bluff and placed along the wood line on the northern side of the field.

Earlier that morning, Colonel Baker, commanding the California brigade, had ridden down the canal towpath to the 1st California Infantry, stationed at Conrad's Ferry. A little after 0900, Baker met with Colonel Wistar, commanding the 1st, and asked if Wistar thought Baker should go down to Stone's headquarters at Edwards' Ferry.

Wistar responded that he didn't know, but his own orders were to remain at Conrad's Ferry unless he heard heavy firing on the bluff, at which time he was to cross over in support. Baker then decided to ride to Edwards' Ferry to see Stone.

Around 1000, Baker arrived at Edwards' Ferry and met with Stone. Baker was informed that McCall's division had advanced to Dranesville. (In fact, by that time, McCall was well on his way back to Langley.) Baker was also told that portions of Devens' and Lee's commands were in Virginia at Ball's Bluff and that Gorman was crossing troops at Edwards' Ferry and would push them to the Leesburg Turnpike.

General Lander was away in Washington, so Stone assigned Baker command of the division's "right wing" in the area of Harrison's Island. Stone would remain at Edwards' Ferry to coordinate the movements of Baker and Gorman.

Baker was ordered to hold any ground previously occupied on the Virginia shore and not yield any ground without resistance. He was not, however, to fight a superior force. In case of heavy firing on the bluff, Baker was to advance forces to support Devens and Lee or to pull all forces back across the river "at your discretion."

Baker asked that these orders be put in writing, and Stone wrote them out.

Shortly before 1100, Baker rode back up the canal towpath toward Harrison's Island to take command of Stone's right wing. On the way, he met Howe and headed for Stone's headquarters. From Howe, Baker learned of Devens' morning fight and Ward's five companies going to his support. Baker immediately ordered an aide to ride ahead and have Colonel Wistar and the 1st California Infantry cross the river and support Devens and Lee.

Baker then rode on toward the island. Howe continued to Stone's headquarters and informed him of the morning skirmish and of Colonel Ward's companies marching to join Devens. Stone replied that Baker was now in command of that wing and that he would arrange things there to suit himself.

Soon after 1100, Stone wrote McClellan, "The enemy has been engaged opposite Harrison's Island; our men behaving admirably." According to McClellan, this was the first intimation that Stone's movements across the river might be more than a mere scout.

McClellan immediately telegraphed McCall to remain at Dranesville, but after learning McCall had already returned to Langley, McClellan ordered McCall and Banks to hold their divisions in readiness for a possible move to support Stone. McClellan also sent a note to Stone asking,

"Is the force of the enemy now engaged with your troops opposite Harrison's Island large? If so, and you require more support than your division affords, call upon General Banks, who has been directed to respond. What force, in your opinion, would it require to carry Leesburg? Answer at once, as I may require you to take it today; and, if so, I will support you on the other side of the river from Darnestown."

Stone responded by saying he thought the enemy was about 4,000 strong, but he believed his command could still occupy Leesburg that day. He ended his message with, "We are a little short of boats."

The Jackson House

Meanwhile, Devens deployed three companies as skirmishers around the Jackson house. While Devens' remaining seven companies waited in the wood line, Colonel Jenifer returned from Fort Evans with Companies B and C, 4th Virginia Cavalry, and Company K, 6th Virginia Cavalry.

Shortly after 1100, skirmishing broke out between Jenifer's and Devens' commands as Duff's Company K, 17th Mississippi Infantry, moved about a quarter of a mile to Jenifer's left. Jenifer had earlier requested reinforcements from Colonel Evans, and soon, two companies of the 18th Mississippi Infantry and one company of the 13th Mississippi Infantry arrived on the right of the Virginia cavalry. As the skirmishing increased in intensity, Jenifer sent for additional troops from Evans.

By noon, the Confederates had pushed Devens' pickets east of the Jackson house.

As Devens' men continued to skirmish, Lieutenant Howe arrived with news that Colonel Baker would soon arrive with his brigade and take command. But Baker, rather than cross over from Harrison's Island immediately and make a commander's reconnaissance of what was about to become a battleground, instead chose to supervise personally the tedious crossing of the troops.

When he first arrived on the island, Baker had been surprised to see the inadequate means of transporting infantry across the river. The only boats available for the crossing from the Maryland side to the island were three flatboats, each capable of carrying forty to fifty men. From the island to the Virginia shore, there were still the three boats used in the morning crossings.

Therefore, the passage of troops across the island was slow. Small trees had to be cut to make poles, and the boats had to be poled up the shore a distance before being loaded and then poled diagonally to the landing site.

Baker spent some time overseeing the raising of a small boat from the canal and also the unsuccessful stretching of a rope from the Maryland shore to the island. Later, others succeeded in extending a rope to the island, making it easier for the boats to cross.29 Shortly after noon, the 1st California Infantry had crossed eight companies onto Harrison's Island, one of which had continued to the Virginia shore.

While the Californians continued crossing to the Virginia shore, Baker sent orders for the 42d New York Infantry to begin crossing over.

At the same time, Devens' position near the Jackson house was becoming precarious. In response to Jenifer's call for more troops, Colonel Evans had sent the 8th Virginia Infantry, commanded by Col. Eppa Hunton, to Jenifer's aid. Hunton had left one of his ten companies at Goose Creek and arrived about noon with almost 400 men on the right of Jenifer's three Mississippi companies.

This brought the total Confederate force facing the 15th Massachusetts Infantry to over 700 men. On the Confederate left Duff's Mississippi company shifted toward the river. With the attack spreading around his flanks, Devens was forced to pull his men back a short distance. Three times, he sent Lieutenant Howe back to locate Baker and hurry up the reinforcements.30 But Baker had yet to cross over from Harrison's Island, and without reinforcements, Devens would have to withdraw his men back to the bluff.

At Edwards' Ferry, Stone had ordered the remainder of Gorman's brigade to cross the river into Virginia along with artillery. As soon as Baker began his advance, Stone would have Gorman's forces strike the retreating Confederates. While his troops were crossing, Gorman remarked to an aide, "My boy, we will sleep at Leesburg tonight."

By 1300, Colonel Cogswell and his 42d New York Infantry were crossing onto Harrison's Island, along with two rifled guns of Battery B, 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery. In the temporary absence of the battery commander, the two-gun section was placed under the command of 1st Lt. Walter Bramhall, 9th New York State Militia.

When he arrived on the island, Cogswell presented Baker with a message from Stone. In the message, Stone estimated Confederate strength at about 4,000, and he instructed Baker to push the enemy if he could.

If Baker drove the Confederates beyond Leesburg, he was not to follow far but establish a strong position near the town. Baker was also told to report frequently so that when Stone was aware that the enemy was falling back, Stone would have Gorman's command come in on the Confederates' right flank. Baker responded that he would cross his forces as rapidly as possible and would advance when his command was strong enough.

Baker, referring to Gorman's attack at Edwards' Ferry, ended his message with, "I hope that your movement below will give an advantage."

About an hour later, Baker crossed the river, reached the top of the bluff, mounted his horse, and assumed command. Upon meeting Colonel Lee, Baker bowed and said politely, "I congratulate you upon the prospect of a battle." While Baker and Lee inspected the positions of the troops, Devens and his men came marching down the path, and Baker congratulated Devens "for the splendid manner in which your regiment behaved this morning."

Baker, feeling he did not have sufficient forces to advance, decided to establish a defensive line across the bluff until more troops had crossed the river. He ordered Devens to place the 15th Massachusetts Infantry just inside the wood line along the northern side of the field, facing south and perpendicular to the 20th Massachusetts Infantry. By now, four companies of the 1st California Infantry had climbed the bluff, and Baker placed two of the companies on the left flank of the 15th Massachusetts Infantry and two companies on the left of the 20th.

Due to a lack of reconnaissance by Baker, the spot assigned to the 15th was a poor one. The ground sloped away from the open field and made it difficult for most of Devens' men to see any Confederate troops unless the enemy approached within yards of the Massachusetts' position. Somewhat out of the fray, many of Devens' men sat down in the woods. The two California companies on Devens' left also lay on the ground, their field of fire partially blocked by the right flank of the 20th.

Crossing behind the four California companies, Colonel Wistar reached the top of the bluff and consulted with Colonel Baker. Baker eagerly sought Wistar's opinion of the disposition of the troops, and the two inspected the line. Wistar, however, offered no opinion.

Instead, he expressed concern about a deep ravine and thick woods on the south side of the field. If the Confederates occupied those positions, he told Baker, the Union left would be outflanked. Wistar asked Baker's permission to extend his line a few paces in that direction, and Baker responded, "I throw the entire responsibility of the left wing to you." Wistar shifted the two California companies toward the ravine, where they discovered and relieved Company D, 20th Massachusetts Infantry.

Jenifer's command and the 8th Virginia Infantry had followed Devens and soon arrived on the western edge of the field and in the woods to the north. Although Devens' right flank was somewhat protected from small arms fire by woods, the dismounted Confederate cavalry and Duff's company moved around the Massachusetts flank and into the rear of Devens' position.

To counter this threat, Devens detached Companies A and I, in skirmish order, and they moved to the rear of Devens' line and faced slightly northward. They were joined on their right by the skirmishers of Company H, 20th Massachusetts Infantry.

As Jenifer's and Hunton's men kept up a steady fire against Baker's right, Stone began to receive reports of heavy firing in the Ball's Bluff area. Assuming that Baker had begun his advance, Stone informed McClellan that "There has been sharp fighting on the right of our line, and our troops appear to be advancing there under Baker. The left, under Gorman, has advanced its skirmishers nearly I mile and, if the movement continues successfully, will turn the enemy's right."

Obviously, Stone was mistaken about any advance by Baker, but his optimistic message prompted McClellan to respond with a coded message, "Take Leesburg." When the message arrived at his headquarters, Stone discovered he did not have the code to decipher it. He sent a cryptic message back to McClellan that "I have the key, but I don't have the box," but McClellan's message was never decoded, and Stone was unaware of its contents. Meanwhile, at Edwards' Ferry, Stone had sent three infantry regiments from Gorman's command across the river.

Although Stone had implied to Baker that these troops were to come in on the right flank of the Confederates confronting his command, only a few of Gorman's troops advanced, halting about a mile from the ferry.

About 1430, Colonel Cogswell and Company C, 42d New York Infantry, crossed from the island to the Virginia shore. Cogswell also brought over one of the rifled guns of Battery B, 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery.

None of the boats being used to transport troops had a bottom strong enough to hold the weight of the gun, so a flatboat was hauled around from the Maryland side of the island, and the gun and crew crossed with Company C. The horses and limber crossed over on a second trip. During Cogwell's crossing, Confederate skirmishers on the bluffs north of the landing site took potshots at the group, but after landing on the Virginia shore, Cogswell had Company C drive them away from the edge of the bluff.

Colonel Cogswell then climbed to the bluff and met with Colonel Baker. As he had with Colonel Wistar, Baker invited Cogswell to examine the line and comment on the disposition of troops. No enemy could be seen, but sporadic small-arms fire still fell on the Union position, and Baker ordered officers and men to lie down to avoid the incoming rounds.

When Baker and Cogswell arrived at Wistar's position on the southeast corner of the field, Baker read aloud Stone's message, giving the estimate of 4,000 enemy troops, then ordered Wistar to send out two companies of skirmishers.

Wistar, now with six companies of the 1st California Infantry on Baker's left, responded by saying that, considering the time it had taken Stone's message to reach Baker, the 4,000 men must then be in front of them.

To send out two companies of skirmishers would be to sacrifice them. Baker replied that he needed to know what was out there and reiterated the order. Wistar then advanced two companies across the open field.

As the first company entered the wood line at the far side, the 8th Virginia Infantry, which was lying in the woods, rose up and, with a yell, charged into the right flank of the lead Californians. Caught off guard, Wistar's men opened fire and, after a short but violent melee, fell back into the wood line on the south side of the field.

Earlier, Evans, now believing that the main Union thrust would be at Ball's Bluff, had sent the rest of Col. Erasmus Burt's 18th Mississippi Infantry (eight companies) and Col. Winfield Scott Featherston's 17th Mississippi Infantry (nine companies) to support Jenifer. About 1500 Burt's men arrived on the right of the 8th Virginia Infantry.

Hunton's troops had been keeping up a steady fire, particularly against the two howitzers posted in the open. Burt's regiment halted, fired a couple of volleys, and charged the guns. The attack drove the gun crews back to the safety of the woods, but Burt was mortally wounded, and his men fell back to the wood line. Lt. Col. Thomas M. Griffin assumed command of the 18th, discovered a gap between his command and the 8th, and detached two companies of the 18th to extend his left. Griffin also sent another of his companies to the right to drive back remnants of the two California companies still on the edge of woods on the south side of the field.

In the meantime, the rifled gun of the Rhode Island battery was hauled up the bluff, limbered to its team of horses, and drawn through the ranks of the 20th Massachusetts Infantry. Just as the gun was unlimbered on a slight rise (the site of a present-day national military cemetery), the 18th Mississippi Infantry and 8th Virginia Infantry opened fire, immediately wounding several crewmen and killing or mortally wounding all the horses.

The frightened horses bolted at the gunfire and dragged the limber back through the 20th's line. Cogswell ordered the remaining crewmen to return fire, but the shells were ineffectual against the Confederates in the thick woods.

About 1530, more of Colonel Featherston's 17th Mississippi Infantry arrived at the battlefield. A 200-yard gap still existed between the 18th Mississippi Infantry and the 8th Virginia Infantry, so Featherston moved into the opening and immediately opened fire on the rifled gun, knocking down the remainder of the crew.

Although wounded, Lieutenant Bramhall remained with the gun and, along with Colonels Wistar and Cogswell and volunteers from the 1st California Infantry, manned the gun to keep it firing.

Even Baker assisted in pushing the gun back into position several times after its recoil. However, Confederate fire was too severe, and the gun fell silent, having fired less than ten rounds. To the right, the two mountain howitzers also sat silent, their crews suffering the same fate as those assigned to the rifled gun.

Small arms fire was growing in intensity on the Union left, and the companies of California troops were beginning to run out of ammunition.

Since most of the troops on both sides were armed with similar-caliber smoothbore muskets, the California troops were able to replenish their ammunition by taking rounds from the cartridge boxes of the Confederate dead. In the center of the Confederate line, the 8th Virginia Infantry was also low on ammunition, with some soldiers having fired their last round. Jenifer sent an urgent request to Evans for more ammunition and provisions and asked if provisions could not be had, that a barrel of whiskey be sent to refresh the men.

On Jenifer's left flank, the three companies of dismounted Virginia cavalry shifted farther left toward Captain Duff's position, and Duff's company was ordered to fall back and join the rest of the 17th Mississippi Infantry on the opposite flank. However, before Duff reached his regiment, the order was countermanded, and Duff's company halted some distance in the rear of the Confederate line, where it remained for the rest of the battle.

Hearing the heavy firing from Edwards' Ferry, Stone believed Baker was still advancing toward Leesburg. Stone informed McClellan that nearly all of his division was across the river, Baker on the right, Gorman on the left, with Baker heavily engaged.

But Baker was not advancing. Instead, he was barely holding his own on the bluff. Shortly before 1700, as the intensity of the Confederate fire continued to shift to Baker's left, he met with Wistar in the southeast corner of the open field to assess the situation.

While standing next to Baker, Wistar received his third wound of the day and was carried down the bluff and back to the island. Also carried back across the river was 1st Lt. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., of Company A, 20th Massachusetts Infantry, who had been wounded twice.42 Holmes would survive the battle and the war to become a Supreme Court justice.

Death of Baker

While Baker remained in the open watching the action, Companies A and H, 42d New York Infantry, arrived on the bluff and were sent into the woods on the south side of the field. There, they drove back the Confederate skirmishers about fifty yards but were, in turn, forced to fall back. Although the Confederates remained relatively unseen in the woods, their small arms fire was taking its toll on anyone standing in the open field.

About 1700, Baker was struck simultaneously by several bullets and killed instantly. A group of men from the California companies rushed forward to recover his body, and it was taken down the bluff and carried back across the river. Few of the Union troops were aware of Baker's death, but the question arose briefly as to who would succeed him in command. Colonel Lee, believing he was the senior officer present, claimed command and ordered a retreat back across the river.

Colonel Cogswell, however, claimed seniority to Lee, to which Lee assented. Cogswell refused to order a retreat, saying it would be impossible to try and recross the river in the presence of an aggressive enemy. Instead, he preferred they try and cut their way through to Gorman's command at Edwards' Ferry.

In preparation for the breakout, Cogswell ordered the four infantry regiments to form a column of attack in the woods along the southeast corner of the field, and the 15th and 20th Massachusetts Infantries began shifting to the left, behind the 1st California Infantry and the three companies of the 42d New York Infantry. As the column was being formed, a few Union troops dragged the rifled gun back and attempted to roll it over the bluff, but fallen trees blocked the way, and it was left in the woods.

Colonel Hunton, seeing the Massachusetts troops withdrawing from his front and the two howitzers left unattended, had his men redistribute the few remaining cartridges so that most of the men would have one round. After having his men fix bayonets, Hunton ordered his command forward, and the Virginians charged across the open field. Two companies of the 20th Massachusetts Infantry rushed out to try and save the two mountain howitzers but were driven back "by a perfect shower of bullets," and the guns were captured.

While Cogswell moved to the head of the column in the woods, an individual appeared on horseback in the field on the right of the three companies of the 42d New York Infantry. Colonel Devens later testified that the individual, whom he did not know, rode a gray horse and waved his hat at the New Yorkers "as an officer would who was calling the troops to come on." Breaking column, some of the New Yorkers charged onto the field, and the 15th Massachusetts Infantry, thinking an order had been given to charge, also started forward. However, Devens and another officer rushed in front of the regiment and brought it to a halt. While Devens was attempting to put his men back in the column, the New Yorkers tumbled back in disorder through the 15th's ranks, and both regiments fell back to the edge of the bluff. Cogswell tried to reorganize his scattered column for another attempt but with no success.

After the charge of the 8th Virginia Infantry, Colonel Hunton informed Colonel Featherston that his ammunition was exhausted. Featherston then ordered the 17th and 18th Mississippi Infantries to advance, without firing, until they were close to the Union line, then fire and charge. Shouting, "Charge, Mississippians, charge! Drive them into the Potomac or into eternity," Featherston led the two regiments forward.

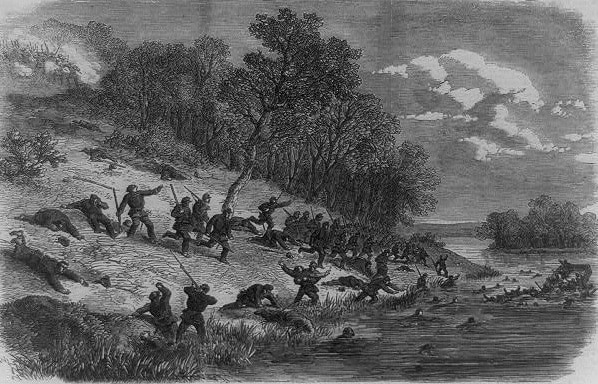

The tragic retreat

Cogswell now realized all was lost and ordered Devens to retreat down the bluff. But Devens refused to accept the verbal order to retreat unless Cogswell repeated it in front of a witness. The order was then repeated in the presence of Maj. John W. Kimball, 15th Massachusetts Infantry, and Devens ordered his men to retreat. News of retreat spread quickly and caused chaos throughout most of the Union ranks as all of the Union troops scrambled over the bluffs and onto the riverbank. Men began climbing, jumping, or tumbling down to the plateau below. Some were injured or even killed when they fell down the steep slope. After reaching the riverbank, Devens tried to establish a skirmish line to fire back up the bluff but soon advised his men that it would be every man for himself and that they should throw their weapons into the river and escape the best they could. Devens tossed his sword into the water and, with the help of a couple of others, managed to float to the island on a large tree branch.

As the Union soldiers crowded on the riverbank in the darkness, the large flatboat arrived, carrying Companies E and K of the 42d New York Infantry. Cogswell ordered the fresh troops and a few of the 20th Massachusetts Infantry to move halfway back up the trail to try and hold off the Confederates and cover the retreat across the river. The boat was then loaded with wounded and unwounded alike and shoved off, but was so overcrowded it quickly tipped over and sank. Those who did not drown managed to return to the Virginia shore or swim to the island. As this was the only large boat then available on the Virginia side of the island, Companies B, D, F, G, and I of the 42d New York Infantry, who were still on the island and unable to cross, watched helplessly as the disaster unfolded on the opposite shore.48 While the Confederates fired from the top of the bluff, the three smaller boats plied the river, laboriously carrying small groups back to the island until they were riddled with bullets and sank.

Officers of the 20th Massachusetts Infantry assisted 54-year-old Colonel Lee down the riverbank, where Lee, a seriously wounded Major Revere, and several other officers and enlisted men tried to escape upriver. When they tried to make a raft by tying fence rails together with their sword belts, it quickly fell apart. They continued upstream, where a portion of Jenifer's cavalry captured them.

Back at the riverbank below the bluff, Capt. William Bartlett of the 20th Massachusetts Infantry shouted to those around him that if they couldn't swim, to follow him upstream. About twenty men from various regiments followed and, in the dark, managed to reach Smart's Mill. Avoiding Confederate cavalry, they found a small sunken skiff, raised it, and crossed over to the island, five men at a time.

In the dark, the Confederates continued to fire down from the bluff into the mass of refugees trapped below. On Harrison's Island, men tried to make rafts of whatever material was at hand and set them adrift, hoping they might float across to the Virginia shore. Capt. Timothy H. O'Meara, Company E, 42d New York Infantry, swam to the island and tried to find another boat but was unable to locate one. He then swam back to the Virginia shore, where he was captured with his company. Capt. Alois Babo and 2d Lt. Reinhold Wesselhoeft, both of the 20th Massachusetts Infantry, tried to assist each other in swimming the river but were both swept away in the swift current. Wesselhoeft's body was found thirteen days later, twenty miles downstream. While the Union troops huddled on the riverbank, part of the 18th Mississippi Infantry worked its way down the ravine on the southern side of the field and opened fire on the men along the shore. Cogswell quickly organized a squad of about a dozen men who were still armed and moved to the mouth of the ravine to stop this fire, but he and the group were surrounded and captured.

About 1830, a courier brought Stone the news of Baker's death. Stone quickly forwarded the news to McClellan and then rode toward the island. All along the towpath lay water-soaked fugitives who had managed to swim over, each with a story of the defeat. Stone also passed the body of Colonel Baker being brought to Edwards' Ferry and stopped briefly to pay his respects. Opposite the island, sporadic firing was still going on, and Stone was told that everyone in Baker's wing had been killed or captured. Stone sent an order to Col. Edward W. Hinks of the 19th Massachusetts Infantry, whose regiment was then crossing onto the island, to secure all wounded and fugitives as soon as possible and to hold the island at all hazards until the wounded had been removed. Then Stone, fearing that the victorious Confederates would now turn on Gorman's troops at Edwards' Ferry, rode down the towpath to order Gorman to withdraw to the Maryland shore.

By 2000, most of the Union forces still on the riverbank below Ball's Bluff had surrendered, although the firing continued intermittently into the night. Some soldiers, however, hid in the dark and throughout the night and the next morning were either captured or made attempts to swim to the island. At 2130, Stone alerted McClellan that he was trying to prevent further disaster and warned that any advance from Dranesville must be made cautiously. Stone also informed McClellan that Gorman's forces on the Virginia shore were being cautiously withdrawn. McClellan, concerned lest Gorman's forces would be withdrawing in the face of an aggressive enemy, ordered Stone to hold the Virginia shore at Edwards' Ferry at all hazards. In Washington, President Lincoln had been anxiously listening to reports of the battle. At 2200, after learning of the death of his friend Baker and the Union defeat, Lincoln sent a message to Stone asking for particulars of the battle. Stone responded, "It is impossible to give full particulars of what is yet inexplicable to me." Later, McClellan ordered General Banks to rush his division to Stone's support.

Still believing McCall was at Dranesville, Stone sent a message to McClellan suggesting that reinforcements be sent up to Goose Creek. It was only then that he learned that McCall had not been at Dranesville all day.

At about 0330, October 22, two of General Banks' brigades arrived at Edwards' Ferry and began to cross the river to reinforce Stone's command. As the day dawned cold and rainy, a Union burial party under a flag of truce crossed at Harrison's Island to bury the Union dead. By evening, the group had buried forty-seven bodies, two-thirds of those found on the battlefield. By noon of that same day, Banks' two brigades had crossed the river and had a brief skirmish before the Confederates withdrew. In the afternoon, General McClellan arrived at Poolesville. He decided the Union position on Harrison's Island was not a favorable one but waited until dark to order any withdrawal. McClellan then ordered all Union troops to withdraw from the island to the Maryland shore. When the last troops reached the Maryland shore, the remaining guns of the 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery fired a salvo at the bluff, a "complement to the rebel commander."

The weather cleared on October 23, and at Edwards' Ferry, the Confederates, realizing that Stone had been reinforced, withdrew to Fort Evans. During the day, McClellan arrived at Edwards' Ferry to take personal command, and in 1915, that evening, he ordered all of Stone's and Banks' forces on the Virginia side of the river at Edwards' Ferry to withdraw. By 0400 the next day, all Union troops had returned to the Maryland shore, which, as McClellan wrote to his wife a few days later, "they should never have left."

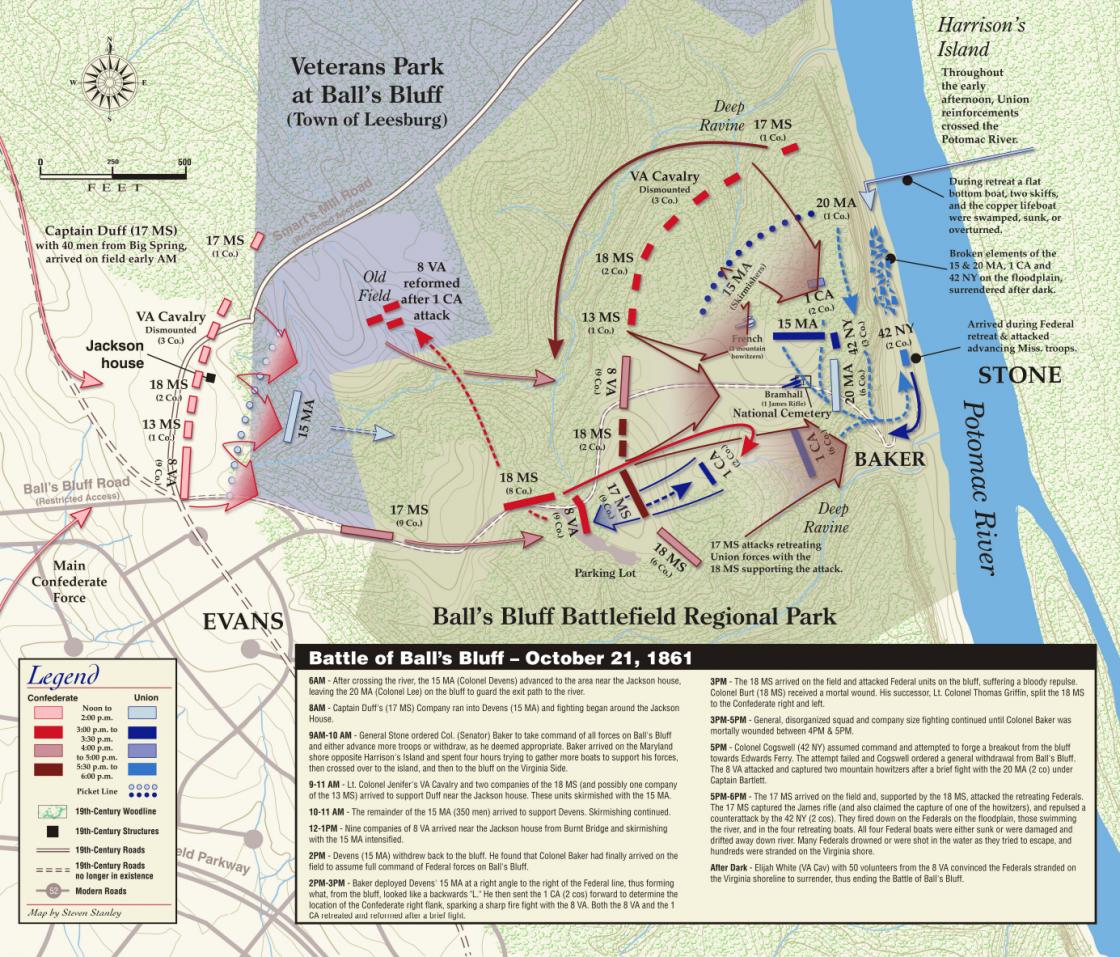

Battle of Ball's Bluff's Map from battlefields.org

Conclusions

What had started out as a surprise attack on a small, unguarded Confederate camp had turned into a military disaster. The opposing forces at Ball's Bluff were evenly matched, with about 1,700 men on each side, but Union casualties were over 900 killed, wounded, and missing. Confederate casualties were comparatively light, about 150 killed, wounded, and missing. The North was still smarting from the previous defeat at the Battle of First Bull Run, and the perceived military incompetence at Ball's Bluff and the death of a popular U. S. senator created an additional public outcry.

Within two months of the Battle of Ball's Bluff, the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War was established to investigate both battles. Concerning Ball's Bluff, General Stone soon became the focus of Northerners who wanted to see someone punished, and he was called before the committee.

Stone testified that the purpose of his operation on October 21 was solely to destroy the supposed Confederate camp. He had not planned to fight a battle that day but allowed most of his troops to cross into Virginia because he thought the Confederates were withdrawing. If the advance of McCall's division to Dranesville had the effect of forcing the Confederates out of Leesburg, "we had nothing to do but to occupy it."

Stone told the congressmen that had he known that McCall's division was not at Dranesville on October 21, he would have immediately withdrawn all of his forces from Virginia. Stone was so sure that McCall was operating on his left flank that he had warned his artillery at Edwards' Ferry to be careful they did not fire on friends "whom I expected to see coming up the other side of Goose Creek." And when McClellan sent Stone a message asking for information about a good road from Darnesville to Edwards' Ferry (McClellan's message actually meant Darnestown, Maryland), Stone assumed that the message was in error and that McClellan had actually meant Dranesville, Virginia.

Stone placed the blame for the defeat squarely on Colonel Baker. Stone said he had placed Baker in command of the troops at Harrison's Island with discretionary orders as to whether to send more troops across the river or to withdraw those already there. Baker was not to fight if the Confederates were in superior force. Stone said, "The whole story after that is that Colonel Baker chose to bring on a battle."

General McClellan, after hearing Stone's version of events, publicly exonerated Stone of any wrongdoing, issuing a circular to the Army saying that "the disaster was caused by errors committed by the immediate Commander, not Genl Stone." McClellan also wrote to his wife that "the man directly to blame for the affair was Col. Baker who was killed he was in command, disregarded entirely the instructions he had received from Stone, and violated all military rules and precautions."

But the Northern press and the radical Republicans on the joint committee needed a living scapegoat. During lengthy hearings on Ball's Bluff, accusations were made that General Stone had returned runaway slaves to their masters, that he might be disloyal, and that he lacked military competence. In February 1862, he was arrested and held for six months in Fort Lafayette, New York, without formal charges ever being placed against him. After his release, Stone was returned to duty but served in various commands as only a staff officer and military clerk. He resigned from the Army in September 1864.

After the Battle of Ball's Bluff, the Union and Confederate Armies went into winter quarters, and it would not be until the spring of 1862 that either would resume military operations. The Confederate Army would withdraw from Northern Virginia south to take positions behind the Rappahannock River, followed by the Union Army sailing down the Potomac River to Fort Monroe, Virginia, to threaten Richmond from the east. Concern for the upper Potomac fords would diminish until September 1862, when the Confederate Army would cross the Potomac near Leesburg to begin the Maryland campaign.