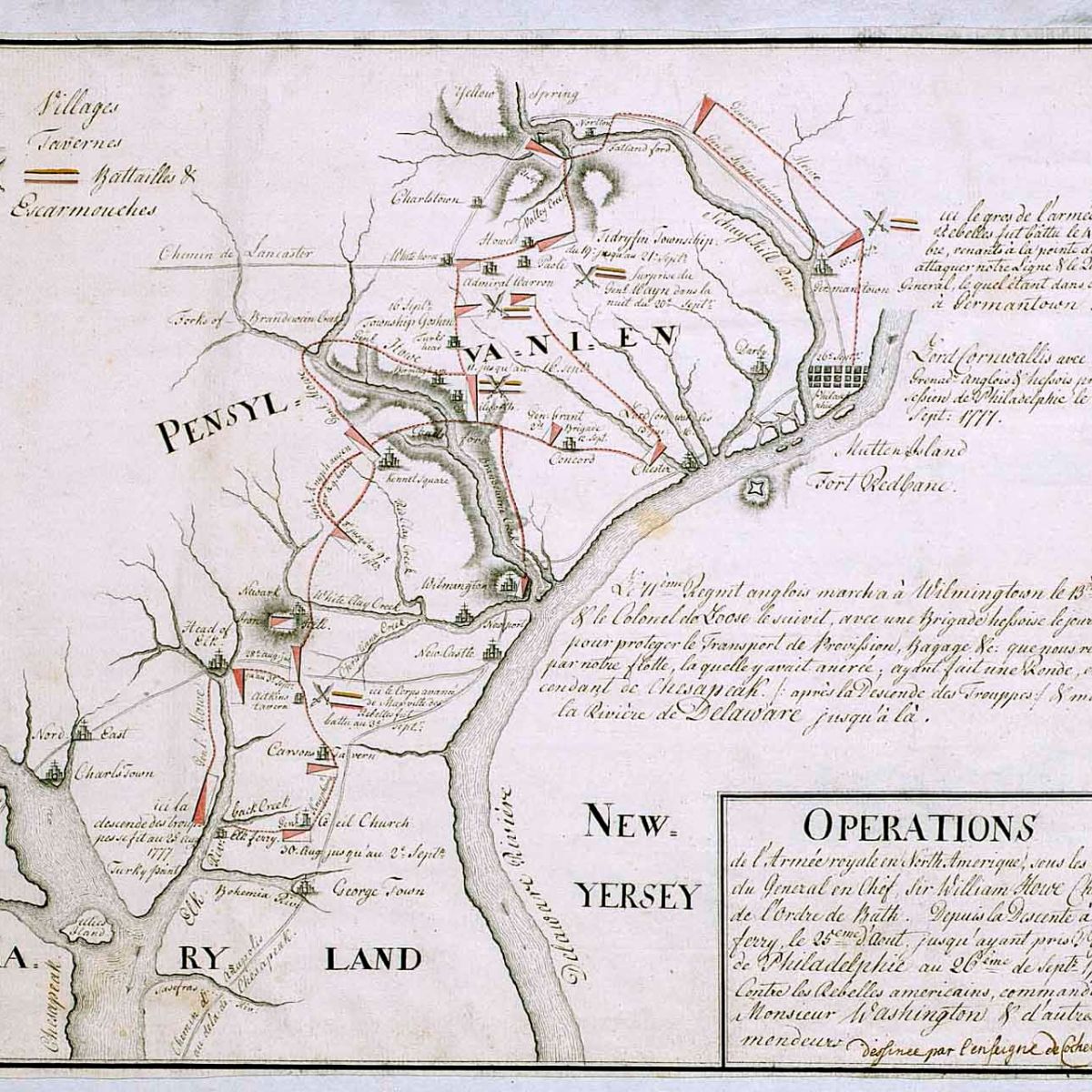

The Battle of Brandywine was fought on September 11, 1777, as part of the Philadelphia campaign. The battle raged between the Continental Army under General George Washington and the British Army under General William Howe. The American forces numbered 11,000, and the British and Hessian forces were approximately 16,500 men strong.

It was a long battle filled with many tactical maneuvers that lasted from sunrise to sunset. Much of the time, the two opposing commanders tried to outwit each other. The result was a British victory but another failed opportunity at capturing the Continental Army. Washington retreated from the field but remained between Howe and Philadelphia.

Howe's Reasoning

The Philadelphia Campaign, while a successful campaign for the British, leaves more questions than answers. General John Burgoyne was marching from Canada to capture the Northern colonies and effectively split the colonies in half. Burgoyne was told that Howe would support his efforts, but during his march, Howe received permission to engage Washington and capture Philadelphia.

Historians are left scratching their heads at this decision. Howe's decision to capture Philadelphia allowed the destruction of Burgoyne's northern army at Saratoga. However, when one digs into the Philadelphia Campaign further, there may be a shred of evidence that suggests a different motive.

It is easy in hindsight to question Howe's decision, but I argue that there were three determining factors that caused him to capture Philadelphia and not join Burgoyne.

- He would overextend his supply lines: If Howe were to march his men towards Burgoyne, he would have been shadowed by Washington. Washington had already shown his effectiveness in attacking the British when they overextended their supply lines during the Battles of Trenton and Princeton.

- The only way to end the war was to destroy Washington's Army: While Saratoga became the turning point of the war, it did not secure an American victory. If Howe had managed to destroy Washington's Army at Brandywine, then Saratoga would be irrelevant. Howe knew that the only way to end the rebellion was to destroy its main army. He had failed twice in New York and knew it. It seemed as though Brandywine offered him another opportunity.

- It was logistically impossible: Logistics are more important in war than tactics, and it is easy to forget that. I argue that the main reason for Howe's decision was a logistical one. It was much easier to feed and shelter his army in the confines of a city. The British army had problems supplying their army throughout the war due to exposed supply lines and guerrilla warfare. Howe's decision to move to Philadelphia was mainly predicated on this.

In my opinion, take it for what you think it is worth: General Howe made the right decision in attacking Brandywine. He almost succeeded in surrounding Washington and politically almost destroyed him. With the victory at Saratoga and the loss at Brandywine, many in Congress began to doubt Washington's competence.

Some began to push for Horatio Gates to be commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, a decision that would have devastated the cause and ultimately ruined the army. Gates proved incompetent at Camden and, according to many witnesses, took credit for Daniel Morgan and Benedict Arnold's accomplishments at Saratoga.

Preparations for Battle

The beginning of the Battle of Brandywine was a chess match. Each commander maneuvers his army to try to find an advantage with the terrain. Washington had to rely on shoddy intelligence, while Howe did his best to avoid another Bunker Hill.

General Howe decided on a risky proposition. He would divide his forces: Knyphsausen would lead his left wing (Approximately 5,000 men) while he and Cornwallis would execute a wide flanking maneuver to the north around the lengthy Continental line.

Knyphausen's attack was to be diversionary while Howe swung around and outflanked the Continentals and trapped Washington. Howe's plan was a gamble and relied on his ability to make Washington believe that his main attack was on Chad's Ford.

General Washington was aggressive, but Brandywine would be decided by his intelligence. If Washington had been given the correct intelligence, then Howe's strategy would have been exploited, but that was not the case. Washington's lines were stretched thin and in a constant state of flux due to Howe's maneuvering.

The Fighting

Then, the sun broke the horizon on September 11, 1777, and it was clear to Washington that the British were approaching Chadds Ford. Knyphausen's column was led by a crack force of riflemen under the command of Major Patrick Ferguson.

Ferguson had developed a breech-loading rifle, and each of his men was equipped with it. Accompanying them was a unit of Tories known as the Queen's Rangers, who skirmished with Maxwell's infantry posted along the road and heights west of the Ford.

As the British vanguard approached, they were met with heavy fire that began to rake the Tory line. Captain Andrew Porter's company of Colonel Thomas Proctor's Continental Artillery opened fire but was poorly aimed and ineffective. Howe's diversion had begun now. Everything hinged on Washington, believing it long enough so that he could be flanked.

Washington noticed the approach and was also given information about a larger force moving around Brandywine Creek. His initial reaction was to prepare for a full assault on the British at Chadd's Ford.

Howe had divided his force, and this would allow the capture of a large portion of his army. Then, new intelligence came in and informed the aggressive General that the larger army was no longer seen. Washington was forced to reevaluate based on his intelligence, and he delayed the attack.

Meanwhile, Knyphausen's men had successfully absorbed the attack from the Continental Line and were pushing forward. Artillery had been ineffective, and the crack riflemen had gradually begun to overwhelm the rebels. The Americans began to fall back across Brandywine Creek, leaving Knyphausen in command of the west side.

Once the retreat across the creek was executed, the battle resumed as a long-range musket and artillery duel. Neither side was particularly effective, but Knyphausen had successfully held Washington's attention while Howe's men continued their march around Brandywine Creek.

Washington continued to receive conflicting reports on Howe's movements. At 2:00 PM, he received a report from Colonel Bland's scouts that said the British were about to fall upon his rear, and Howe's column was forming on Osborne Hill.

Washington ordered Major General John Sullivan north to meet the threat while Major Generals Alexander and Stephens swung their divisions northeast. Washington kept Greene's division near Chadds Ford. Shoddy intelligence continued to fail Washington, and by 4:00 PM, Howe attacked Sullivan.

Sullivan realized his men were out of position, but before he could reform his line, Howe launched his attack. The initial thrust confused the Americans and threw them into chaos. Sullivan managed to rally his men and put forth a credible defense. American artillery effectively slashed through the British lines, but Howe and his subordinate Cornwallis were relentless.

They kept pushing forward. Washington, hearing the loud noises from his right rear, made fast for Birmingham Hill with Greene's Division. He arrived just as Sullivan's front was beginning to collapse. The exhausted men had put up a credible defense but could hold the British no longer.

Nathanael Greene wisely threw his men into the line, which gave Sullivan's men enough time to retreat. This move saved much of the army, and its execution was magnificent. Greene's men executed a fighting withdrawal on short notice. Greene's discipline paid off as the men executed the orders to near perfection and under heavy duress. Knyphausen forged Chadd's Ford and collapsed its defenders.

The American army was in full retreat, and the British were in hot pursuit. When night fell, the darkness put an end to the pursuit. Howe had once again outflanked Washington and pushed the Continental Army away from Philadelphia. Now, the capital was exposed.

Conclusion of Brandywine

Brandywine was a disaster for the Americans and for General Washington. He had already received much criticism for the disaster in New York, and although his victories in Trenton and Princeton had revived his support, there were many detractors.

Horatio Gates seemed to have Burgoyne under control after victories at Bennington and Freeman's Farm, and some in Congress had begun considering him as a replacement for Washington.

The damage done to the Continental Army at Brandywine was enormous. They lost 1,100 men and 11 cannons, and the capital of Philadelphia was now in imminent danger of falling into enemy hands. Washington's intelligence service was abysmal and needed reform.

It had broken down and cost Washington a great opportunity to land a devastating blow on Howe when he divided his army. Although they were badly beaten, the Americans managed to stay between the British and Philadelphia, but Washington knew he needed a miracle if he wished to push the British back.