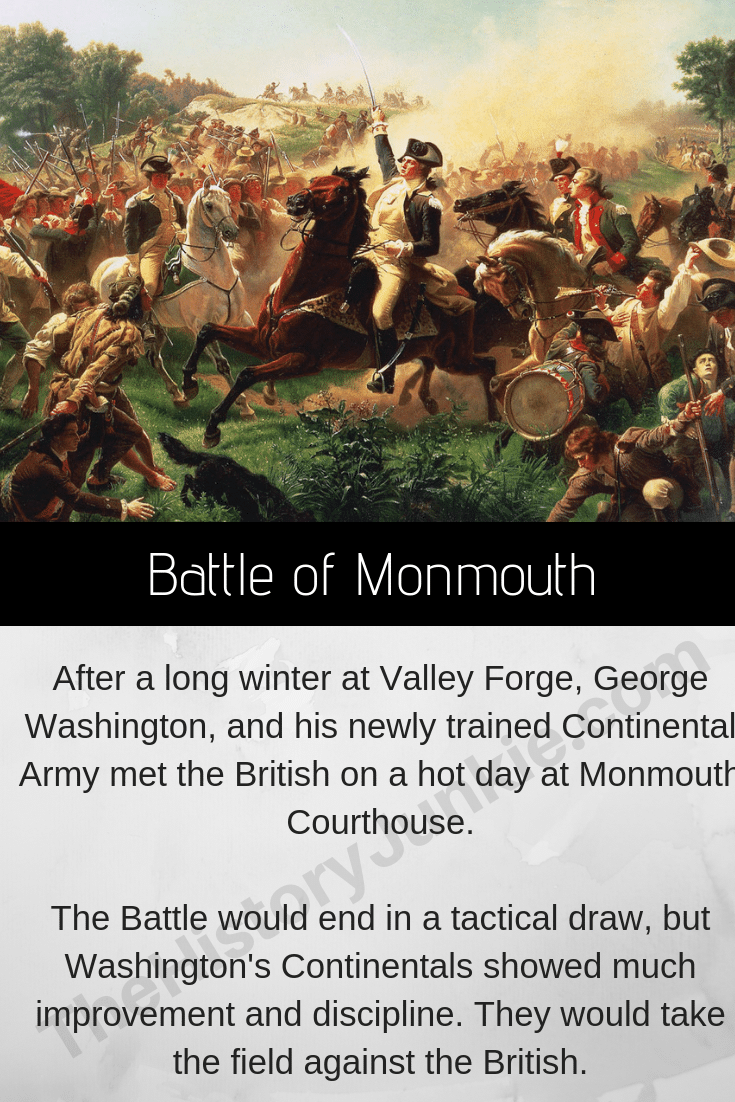

The Battle of Monmouth took place on June 28, 1778, and was the last major engagement in the northern theatre during the American Revolutionary War.

During the winter at Valley Forge, the Continental Army was drilled by Baron Von Steuben and Marquis de Lafayette, and the result would be an army that could look the British regulars in the eye and not run. When the winter lifted, a new army would emerge.

An army that would stare down the barrels of a British musket and bayonet and not run.

After Burgoyne's loss at Saratoga, France entered the war and forced the British to switch from a localized war in their colonies to a global war. General Henry Clinton was ordered to evacuate Philadelphia and concentrate his troops at the main base of operations in New York.

Clinton and his force of 11,000 (1,000 were loyalists from Philadelphia) would begin to march to New York on June 18. During their march, the Americans would slow their advance by burning bridges, muddying wells, and harassing their supply lines.

The weather was scolding hot, and many men would die of heat stroke on both sides.

American Perspective

During the winter, the Continental Army had changed. General George Washington had employed a drillmaster from Prussia, Baron von Steuben, to drill the Continental troops. The entire winter, he not only drilled the men but educated them in the ways of Europe.

He taught them the proper way to use a bayonet, proper formations, and maintenance. This training resulted in the finest army America had ever seen.

When Spring came, there was a new perspective on the war. France was now allied with the colonies, and Saratoga had turned the war to favor the Americans.

Washington was reinforced with General Charles Lee, who had recently returned from being a British captive, and a young Frenchman named Marquis de Lafayette.

With American resolve at its peak and Britain in a position of vulnerability, General George Washington wanted to strike.

When the British moved out of Philadelphia, Washington entered the city and placed Benedict Arnold in command. He began to send small regiments to harass the British on their march and guess correctly that General Henry Clinton would take the southerly route towards New York and planned so.

However, when General George Washington ordered a council of war, not all agreed with him. General Charles Lee believed that it was not necessary to attack the British and risk a decisive battle. He believed that with France entering the war, the British would eventually give up.

He was not alone in that opinion. However, General Lafayette thought otherwise. Lafayette and many others were in favor of an attack and believed that the British were vulnerable. Washington agreed.

British Perspective

From the outside looking in, the British appeared to be in control. General William Howe had successfully defeated the Continental Army at New York and proceeded to capture the rebel capital of Philadelphia.

Even though General Washington was constantly retreating, he was able to keep the Continental Army intact and, with it, hope. Fortunes once again changed for the British when General Burgoyne stumbled into Saratoga and lost his entire army.

Unlike the European wars, victory was not reached by capturing cities but rather by destroying armies, and in that department, Britain had failed miserably. General William Howe resigned his position, and it was given to his rival, General Henry Clinton.

Due to the Franco-American Alliance, Britain no longer considered the rebels the main threat but rather the French. They decided to abandon Philadelphia and move more to a defensive position in the North.

In May of 1778, General Henry Clinton received his orders to march back from Philadelphia to New York. Upon arrival, he was to send 5,000 of his troops to the West Indies for offensive operations against the French; 3,000 men were sent to the Southern Colonies, and the rest were to stay in New York.

Intelligence had reported that the French sent a fleet and 4,000 men for the Americas under Admiral d'Estaing, but they did not know where he would land.

With this news, General Clinton abandoned Philadelphia and marched towards New York. He would soon run into General George Washington and his newly trained Continental army

Fighting

General Charles Lee was considered by many in America to be the most talented field General in the American army. Those accolades would prove to be inaccurate early on June 28.

At about 9:00 am, the cautious Lee would move his 5,000 men in an odd series of movements, which would trigger an engagement with General Henry Clinton's rear guard of about 1,500 men.

These unorganized movements alerted Clinton to a significant American force in his rear. He quickly ordered Knyphausen to watch his left flank and to proceed to march.

He then ordered 14 battalions led by General Charles Cornwallis to turn and meet Lee's vanguard before the main American force could reach the field.

With Cornwallis in place, he would move his right towards Lee's left flank. Lee quickly lost control of the situation and began to retreat.

General George Washington arrived at the Battle of Monmouth and was disgusted with Lee's unwillingness to fight the British. A heated exchange took place, which resulted in the only report of Washington cursing in the entire war.

Years later, when Brigadier General Charles Scott was asked if he had ever heard General Washington swear, he said, Yes sir, he did once," Scott replied. "It was at Monmouth and on a day that would have made any man swear. Charming! Delightful! Never have I enjoyed such swearing before or since. Sir, on that memorable day, he swore like an angel from heaven!

Washington would rally the troops and organized a new line, which slowed the British advance until the rest of the army was in the field. The arriving units formed a main line of defense behind the West Ravine.

General Henry Knox and General Nathanael Greene brought up their artillery. In response, General Henry Clinton brought up his own artillery pieces, and they began to fire back and forth in one of the most intense artillery exchanges of the war. The soldiers fought in extremely close quarters throughout the entire day.

Many would drop dead due to the extreme heat, but the American lines did not break like they had in the past. A last British push forced Washington to fall back.

Washington fell back to his last line. He could not have chosen a better piece of ground.

Here, he was perched on the high ground, which made it difficult to attack, and behind him was a small forest that allowed the Americans to maneuver undetected by the British.

General Wayne deployed his line slightly in front while General Alexander positioned his men on the left and General Nathanael Greene positioned himself on the right.

General Lafayette would be in charge of the reserves.

Clinton prepared his men for what he believed to be the last blow. He attacked the left, but the newly trained American army stood fast and inflicted heavy casualties.

The British fell back, and the Americans counterattacked. The counterattack would push the exhausted British troops back for good on the north side.

On the other side, Cornwallis launched an assault on Greene's position. These were probably the best troops in General Clinton's army, but they were ripped apart by right musket fire and well-placed artillery on Comb's Hill.

Cornwallis took heavy casualties and was pushed back. The rest of the British army fell back as well. General Washington organized a counterattack, but the men were too exhausted from the heat.

Outcome

The Battle of Monmouth was technically a draw, with the American army holding the field the next day. It was the last major battle in the northern theatre and the largest battle in the war, as well as the largest artillery duel.

General Charles Lee was relieved of command, and Washington reluctantly launched a court-martial.

He was found guilty and suspended for one year. However, his constant verbal attacks on Washington made it impossible for even his most loyal supporters to support him. The Battle of Monmouth ended his military career.

The Battle of Monmouth also proved that the newly trained Continental Army could stand up against the British regulars.