The Battle of Plattsburgh ended the final British invasion of the northern states of the United States during the War of 1812.

An army under Lieutenant-General Sir George Prévost and a naval squadron under Captain George Downie converged on the lakeside town of Plattsburgh, New York.

Plattsburgh was defended by New York and Vermont militia and detachments of regular troops of the United States Army, all under the command of Brigadier General Alexander Macomb and ships commanded by Master Commandant Thomas Macdonough.

Background

British plans

In 1814, Napoleon abdicated the throne of France. This provided Britain the opportunity to send 16,000 veteran troops to North America.

The Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, the Earl of Bathurst, sent instructions to Lieutenant-General Sir George Prévost, the Commander-in-Chief in Canada and Governor-General of Canada, authorizing him to launch offensives into American territory, but cautioning him against risking being cut off by advancing too far.

Bathurst suggested that Prévost should give first priority to attacking Sackett's Harbor on Lake Ontario, where the American fleet on the lake was based, and seizing control of Lake Champlain as a secondary objective.

Prévost lacked the means to transport the necessary troops and supplies for them up the Saint Lawrence River to attack Sackett's Harbor.

Furthermore, the American ships controlled Lake Ontario, making an attack impossible until the British launched a battleship (HMS St. Lawrence) on the lake, too late in the year for major operations.

Prévost, therefore, prepared to launch his major offensive to Lake Champlain, up the Richelieu River. (Since the Richelieu, also known as the Rich, was the only waterway connecting Lake Champlain to the ocean, trade on the lake naturally went through Canada.)

Prévost's choice of route on reaching the lake was influenced by the attitude of the American state of Vermont, on the eastern side of the lake.

The state had shown itself to be less than wholeheartedly behind the War, and its inhabitants readily traded with the British, supplying them with all the cattle consumed by the British army and even military stores such as masts and spars for British warships on Lake Champlain.

To spare Vermont from becoming a seat of war, Prévost, therefore, determined to advance down the western New York State side of the lake. The main American position on this side was at Plattsburgh.

Prévost organized most of his troops into a division numbering 11,000 under Major General Sir Francis de Rottenburg, the Lieutenant Governor of Lower Canada.

The division consisted of the 1st Brigade of Peninsular veterans under Major General Frederick Philipse Robinson (3/27th, 39th, 76th, and 88th Regiments of Foot), the 2nd Brigade of troops already serving in Canada under Major General Thomas Brisbane (2/8th, 13th and 49th Regiments of Foot, the Regiment de Meuron, the Canadian Voltigeurs, and the Canadian Chasseurs) and the 3rd Brigade of troops from the Peninsula and various garrisons under Major General Manley Power (3rd, 5th, 1/27th and 58th Regiments of Foot).

Each brigade was supported by a battery of five 6-pounder guns and one 5.5-inch howitzer of the Royal Artillery. A squadron of the 19th Light Dragoons was attached to the force.

There was some tension within the force between the brigade and regimental commanders who were veterans of the Peninsular War or of earlier fighting in Upper Canada and Prévost and his staff.

Prévost had not endeared himself by complaining about the standards of dress of the troops from the Peninsular Army, where the Duke of Wellington had emphasized musketry and efficiency above turnout.

Furthermore, neither Prévost, de Rottenburg nor Prévost's Adjutant General (Major General Edward Baynes) had the extensive experience of battle gained by their brigade commanders. All three officers were known for their caution and hesitancy.

Prévost's Quartermaster General, Major General Thomas Sydney Beckwith, was a veteran of the early part of the Peninsular campaign, but even he was to be criticized, mainly for failures in intelligence.

American defenses

On the American side of the frontier, Major General George Izard was the American commander along the Northeast frontier.

In late August, Secretary of War John Armstrong ordered Izard to take the majority of his force, about 4,000 troops, to reinforce Sackett's Harbor.

Izard's force departed on 23 August, leaving Brigadier General Alexander Macomb in command at Plattsburgh with only 1,500 American regulars. Most of these troops were recruits, invalids, or detachments of odds and ends.

Macomb ordered General Benjamin Mooers to call out the New York militia and appealed to the governor of Vermont for militia volunteers. Up to 2,000 militia eventually reported to Plattsburgh.

However, the militia units were mostly untrained, and hundreds of them were unfit for duty. Macomb put the militiamen to use digging trenches and building fortifications.

Macomb's main position was a ridge on the south bank of the Saranac River. Its fortifications had been laid out by Major Joseph Gilbert Totten, Izard's senior Engineer officer, and consisted of three redoubts and two blockhouses linked by other fieldworks.

The position was reckoned to be well enough supplied and fortified to withstand a siege for three weeks, even if the American ships on the lake were defeated and Plattsburgh was cut off. After Izard's division departed, Macomb continued to improve his defenses.

He even created an invalid battery on Crab Island, where his hospital was sited, that was to be manned by sick or wounded soldiers who were at least fit to fire the cannon.

The townspeople of Plattsburgh had so little faith in Macomb's efforts to repulse the invasion that by September, nearly all 3,000 inhabitants had fled the city. Plattsburgh was left occupied only by the American army.

Naval Background

The British had gained naval superiority on Lake Champlain on 1 June 1813, when two American sloops pursued British gunboats into the Richelieu River and were forced to surrender when the wind dropped, and they were trapped by British artillery on the banks of the river.

They were taken into the British naval establishment at Ile aux Noix under Commander Daniel Pring. Their crews, and those of several gunboats, were temporarily reinforced by seamen drafted from ships of war lying at Quebec under Commander Thomas Everard, who, being senior to Pring, took temporary command.

They embarked 946 troops under Lieutenant Colonel John Murray of the 100th Regiment of Foot and raided several settlements on both the New York and Vermont shores of Lake Champlain during the summer and autumn of 1813.

The losses they inflicted and the restriction they imposed on the movement of men and supplies to Plattsburgh contributed to the defeat of Major General Wade Hampton's advance against Montreal, which finally ended with the Battle of the Chateauguay.

Lieutenant Thomas MacDonough, commanding the American naval forces on the Lake, established a secure base at Otter Creek (Vermont) and constructed several gunboats.

He had to compete with Commodore Isaac Chauncey, commanding Lake Ontario, for seamen, shipwrights, and supplies, and was not able to begin constructing larger fighting vessels until his second-in-command went to Washington to argue his case to Secretary of the Navy, William Jones.

Naval architect Noah Brown was sent to Otter Creek to superintend construction. In April 1814, the Americans launched the corvette USS Saratoga with 26 guns and the schooner USS Ticonderoga with 14 guns (originally a part-completed steam vessel).

Together with the existing sloop-rigged USS Preble of 7 guns, they gave the Americans naval superiority, and this allowed them to establish and supply a substantial base at Plattsburgh.

Only a few days before the Battle of Plattsburgh, the Americans also completed the 20-gun brig USS Eagle.

The loss of their former supremacy on Lake Champlain prompted the British to construct the 36-gun frigate HMS Confiance at Ile aux Noix. Captain George Downie was appointed to command soon after the frigate was launched on August 25, replacing Captain Peter Fisher, who in turn had superseded Pring.

Like MacDonough, Downie had difficulty obtaining men and materials from the senior officer on Lake Ontario (Commodore James Lucas Yeo), and MacDonough had intercepted several spars that had been sold to Britain by unpatriotic Vermonters. (By tradition, Midshipman Joel Abbot destroyed several of these in a daring commando-type raid.)

Downie could promise to complete Confiance only on 15 September, and even then, the frigate's crew would not have been exercised.

Prévost was anxious to begin his campaign as early as possible to avoid the bad weather of late autumn and winter and continually pressed Downie to prepare Confiance for battle more quickly.

Invasion

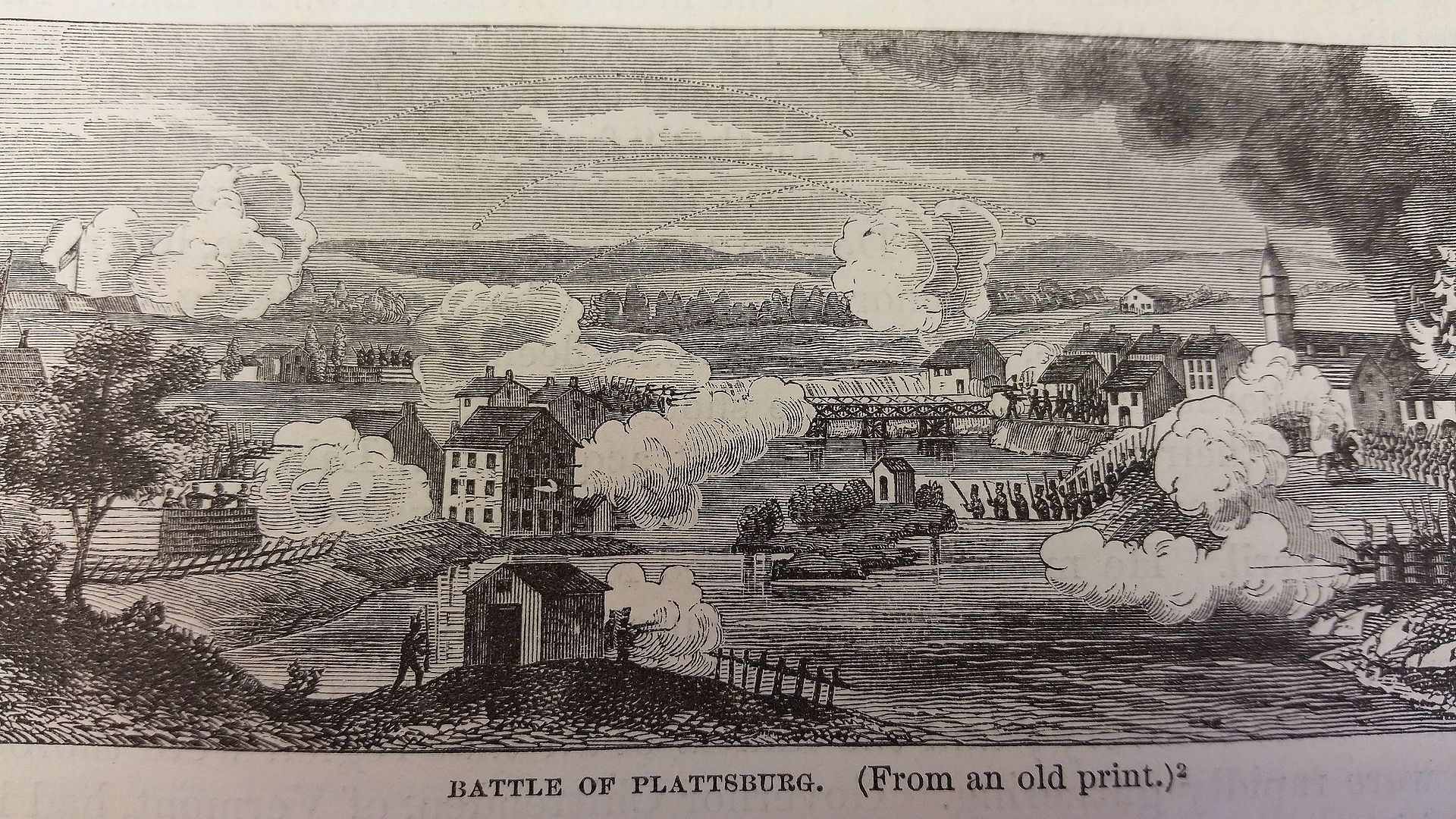

On 31 August, Prévost began marching south. Macomb sent forward 450 regulars under Captain Sproul and Major John E. Wool, 110 riflemen under Major Daniel Applying, 700 New York militia under Major General Benjamin Mopers, and two 6-pounder guns under Captain Leonard to fight a delaying action. At Chazy, New York, they first made contact with the British.

Slowly falling back, the Americans set up roadblocks, burned bridges, and mislabeled streets to slow down the British. The British nevertheless advanced steadily, not even deploying out of a column of march or returning fire, except by flank guards.

When Prévost reached Plattsburgh on 6 September, the American rearguards retired across the Saranac, tearing up the planks from the bridges. Prévost did not immediately attack.

On 7 September, he ordered Major General Robinson to cross the Saranac, but to Robinson's annoyance, Prévost had no intelligence on the American defenses or even the local geography.

Some tentative attacks across the bridges were repulsed by Wool's regulars.

Prévost abandoned his efforts to cross the river for the time being and instead began constructing batteries.

The Americans responded by using cannonballs heated red-hot to set fire to sixteen buildings in Plattsburgh, which the British were using as cover, forcing the British to withdraw farther away.

On 9 September, a night raid across the Saranac River by 50 Americans led by Captain George McGlassin destroyed a British Congreve rocket battery only 500 yards (460 m) from Fort Brown, one of the three main American fortifications.

While skirmishing and artillery fire continued, the British located a ford (Pike's Ford) across the Saranac 3 miles (4.8 km) above Macomb's defenses.

Prévost planned that, once Downie's ships arrived, they would attack the American ships in Plattsburgh Bay. Simultaneously, Major General Brisbane would make a feint attack across the bridges while Major General Robinson's brigade would cross the Ford to make the main attack against the American left flank, supported by Major General Power's brigade.

Once the American ships had been defeated, Brisbane would make his feint attack into a real one.

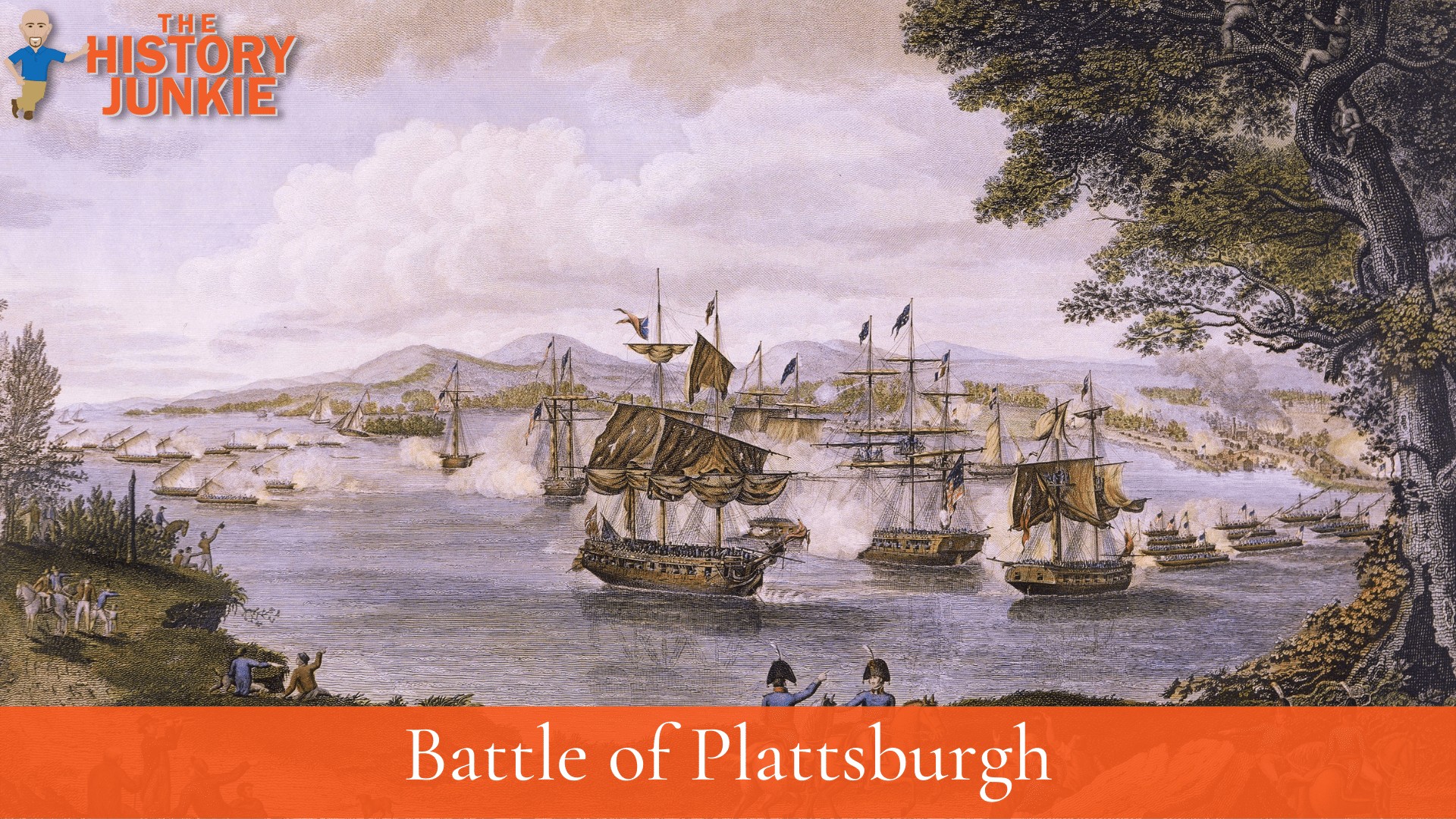

Naval battle

Prelude

McDonough had sent some of his gunboats to harass Provosts' advance, but he knew that his fleet was outgunned, particularly in long guns.

He, therefore, withdrew into Plattsburgh Bay, where the British would be forced to engage at close range, at which the American and British squadrons would be roughly even in numbers and weight of short-range carronade.

He used the time before Downie arrived to drill his sailors and make preparations to fight at anchor. The ships were anchored in line from north to south in the order Eagle, Saratoga, Ticonderoga, and Preble.

They all had both bow and stern anchors, with "springs" attached to the anchor cables to allow the ships to be slewed through a wide arc.

MacDonough also laid out extra kedge anchors from the quarters of his flagship Saratoga, which would allow him to spin the ship completely around.

The ten American gunboats were anchored in the intervals between the larger vessels.

Although the British sloops and gunboats under Commander Pring were already on the Lake and at anchor near Chazy and had set up a battery on Isle La Motte, Vermont, it took two days to tow the frigate Confiance up the Sorel River from Ile aux Noix, against both wind and current.

Downie finally joined the squadron on 9 September. Carpenters and riggers were still at work on the frigate, and the incomplete crew was augmented by a company of the 39th Foot.

To Prévost's fury, Downie was unable to attack on 10 September because the wind was unfavorable.

During the night, the wind shifted to the northeast, making an attack feasible. The British squadron sailed in the early hours of 11 September and announced their presence to Prévost's army by "scaling" the guns i.e. firing them without a shot to clear scale or rust from the barrels.

Shortly after dawn, Downie reconnoitered the American dispositions from a rowing boat before ordering the British squadron to attack.

Addressing his crew, he told them that the British Army would storm Plattsburgh as soon as the ships engaged, "and mind doesn't let us be behind."

Battle

At about 9 am, the British squadron rounded Cumberland Head close-hauled in line abreast, with the large ships to the north initially in the order Chubb, Linnet, Confiance, and Finch, and the gunboats to the south.

It was a fine autumn day, but the wind was light and variable, and Downie was unable to maneuver Confiance to the place he intended across the head of MacDonough's line.

As Confiance suffered increasing damage from the American ships, he was forced to drop anchor between 300 and 500 yards from MacDonough's flagship, the Saratoga.

He then proceeded deliberately, securing everything before firing a broadside that killed or wounded one-fifth of Saratoga's crew.

MacDonough was stunned but quickly recovered; and a few minutes later, Downie was killed.

Elsewhere along the British line, the sloop Chubb was badly damaged and drifted into the American line, where her commander surrendered.

The brig Linnet, commanded by Pring, reached the head of the American line and opened a raking fire against the USS Eagle.

At the tail of the line, the sloop Finch failed to reach station and anchor, and although hardly hit at all, Finch drifted aground on Crab Island and surrendered under fire from the 6-pounder gun of the battery manned by the invalids from Macomb's hospital.

Half the British gunboats were also hotly engaged at this end of the line. Their fire forced the weakest American vessel, the Preble, to cut its anchors and drift out of the fight.

The Ticonderoga was able to fight them off, although it was engaged too hotly to support MacDonough's flagship.

The rest of the British gunboats apparently held back from action, and their commander later deserted.

After about an hour, the USS Eagle had the springs to one of her anchor cables shot away and was unable to bear to reply to HMS Linnet's raking fire.

Eagle's commander cut the remaining anchor cable and drifted down towards the tail of the line before anchoring again astern of the USS Saratoga and engaging HMS Confiance but allowing Linnet to rake Saratoga.

Both flagships had fought each other to a standstill. After Downie and several of the other officers had been killed or injured, Confiance's fire had become steadily less effective, but aboard USS Saratoga, almost all the starboard-side guns were dismounted or put out of action.

MacDonough ordered the bow anchor cut and hauled in the kedge anchors he had laid out earlier to spin Saratoga around. This allowed Saratoga to bring its undamaged port battery into action.

Confiance was unable to return the fire. The frigate's surviving Lieutenant tried to haul in on the springs to his only anchor to make a similar maneuver but succeeded only in presenting the vulnerable stern to the American fire. Helpless, Confiance could only surrender.

MacDonough hauled in further on his kedge anchors to bring his broadside to bear on HMS Linnet. Pring sent a boat to Confiance to find that Downie was dead and the Confiance had struck its colors. The Linnet also could only surrender after being battered almost into the sinking.

The British gunboats withdrew unmolested.

The surviving British officers boarded Saratoga to offer their swords (of surrender) to MacDonough. When he saw the officers, MacDonough replied, "Gentlemen, return your swords to your scabbards; you are worthy of them."

Commander Pring and the other surviving British officers later testified that MacDonough showed every consideration to the British wounded and prisoners.

Many of the British dead, not including the officers, was buried in an unmarked mass grave on nearby Crab Island, which was the site of the military hospital during the battle, where they remain today.

Land battle

Although Prévost's attack was supposed to coincide with the naval engagement, it was slow to get underway.

Orders to move were apparently not issued until 10 a.m. when the battle on the lake had been underway for over an hour.

The American and British batteries settled down to a duel in which the Americans gained a slight advantage, while Brisbane's feint attack at the bridges was easily repulsed.

When a messenger arrived and notified Prévost that Downie's ship had been defeated on the lake, he realized that without the navy to supply and support his further advance, any military advantage gained by storming Plattsburgh would have been worthless.

Prévost considered he, therefore, had no option but to retreat and called off the assault. Bugle calls ordering the retreat sounded out along the British lines.

Robinson's brigade had been misdirected by some British staff officers and missed the Ford, which was their objective.

Once they had retraced their steps, Robinson's brigade, led by eight companies of light infantry, soon drove the defenders back, and the British had crossed the Ford and were preparing to advance when the orders arrived from Prévost to call off the attack.

The light company of the British 76th Regiment of Foot had been skirmishing in advance of the main body.

When the bugle calls to retire were heard, it was too late, and they were surrounded and cut off by overwhelming numbers of American militia.

Captain John Purchas, commanding the company, was killed in the act of waving a flag of truce (his white waistcoat). Three officers and 31 other ranks of the 76th were made prisoners.

The 76th also suffered one dead and three wounded.

Major General Brisbane protested the order to retreat but complied. The British began their retreat to Canada after dark.

Although the British soldiers were ordered to destroy ammunition and stores they could not easily remove, large quantities of these were left intact.

There had been little or no desertion from the British army during the advance and the skirmishing along the Saranac, but during the retreat, at least 234 soldiers deserted.

The British casualties during the land engagement from 6-11 September were 37 killed, 150 wounded, and 57 missing. Macomb reported 37 killed, 62 wounded, and 20 missing, but these losses were for the regular U.S. Army troops only.

Historian William James remarked that the "general return of loss among the militia and volunteers nowhere appears."

Historian Keith Herkalo says that General Macomb informed his father that the American loss "in the land battle" was 115 killed and 130 wounded, a figure which suggests considerable casualties among the militia and volunteers.

Results

MacDonough's victory had stopped the British offensive in its tracks. Also, Prévost had achieved what the U.S. government had been unable to do for the entire war up to that point: to bring the state of Vermont into the war.

The British had used their victories at the Battle of Bladensburg and the Burning of Washington to counter any U.S. demands during the peace negotiations up to this point. The Americans were able to use the repulse at Plattsburgh to demand exclusive rights to Lake Champlain and deny the British exclusive rights to the Great Lakes.

The victory at Plattsburgh and the British failure at the Battle of Baltimore, which came a few days later, denied the British any advantage they could use to make demands for territorial gains in the Treaty of Ghent.

The failure at Plattsburgh, with other complaints about his conduct of active operations, resulted in Sir George Prévost being relieved of command in Canada.

When he returned to Britain, his version of events was accepted at first. As was customary after the loss of a ship or a defeat, Captain Pring and the surviving officers and men of the squadron faced a court-martial, which was held aboard HMS Gladiator at Portsmouth between 18 and 21 August 1815.

The court commended Pring and honorably acquitted all of those charged.

The dispatches of Sir James Yeo were published about the same time and emphatically placed the blame for the defeat on Prévost for forcing the British squadron into action prematurely.

Prévost, in turn, demanded a court-martial to clear his name but died in 1816 before it could be held.

Alexander Macomb was promoted to Major General and became commanding general of the United States Army in 1828. Thomas MacDonough was promoted to Captain (and given the honorary rank of Commodore for his command of multiple ships in the battle) and is remembered as the "Hero of Lake Champlain."

To honor the American commanders, Congress struck four Congressional Gold Medals, a record number for the time. These were awarded to Captain Thomas Macdonough, Captain Robert Henley, Lieutenant Stephen Cassin of the U.S. Navy, and Alexander Macomb.

Macomb and his men were also formally given the thanks of Congress.