Date: January 3, 1777.

Region: Middle Colonies, New Jersey.

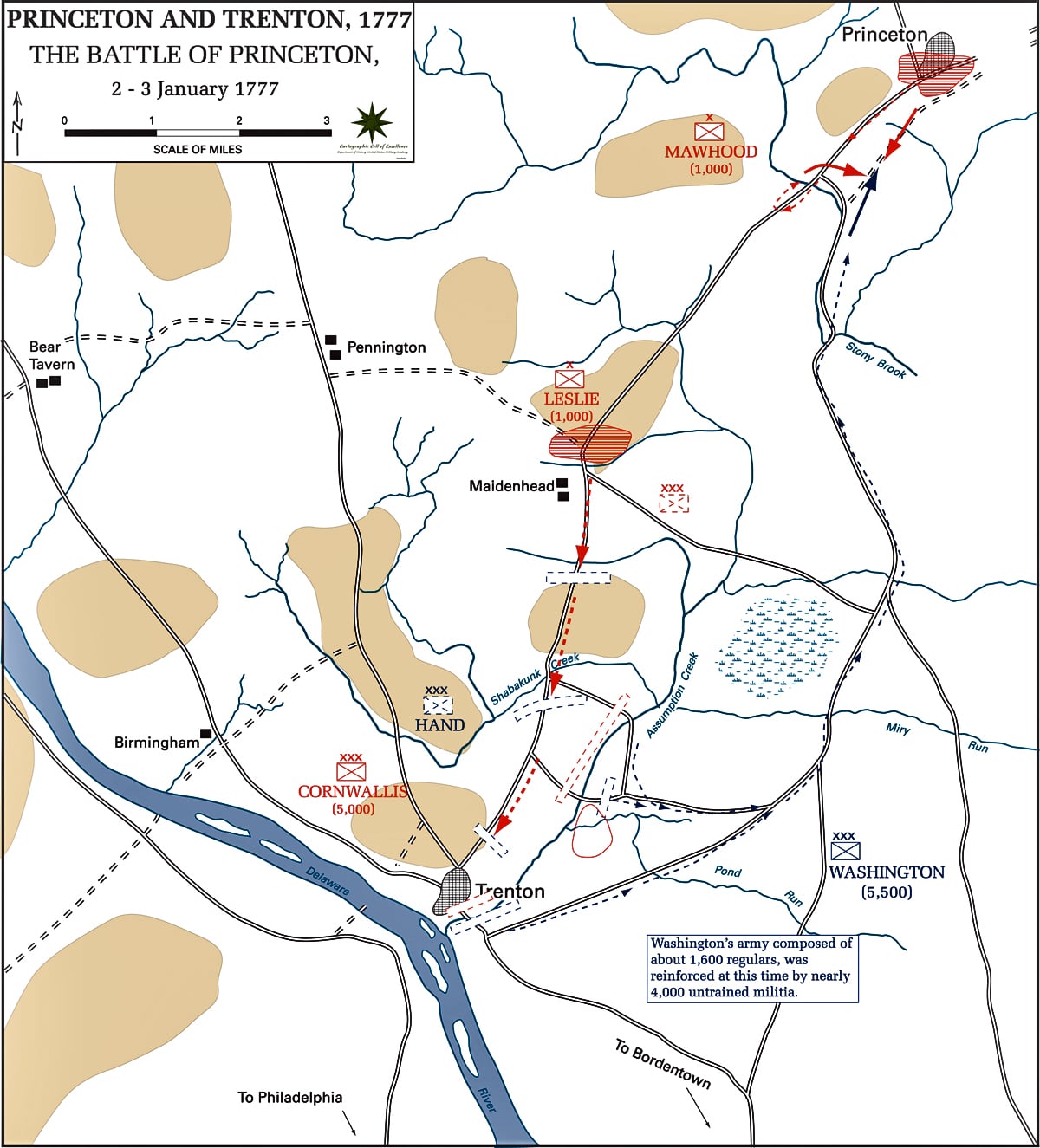

Opposing Forces: British: 1,200; American: 4,600 men and artillery.

Subscribe to American Military History Podcast

British Perspective: On the cold evening of January 2, 1777, General Cornwallis and a 5,500-man force reached Trenton, New Jersey. His arrival at the distant outpost in the dead of winter was triggered by General Washington’s surprise attack against the isolated town just one week earlier, on December 26, 1776. The strike decimated Col. Johann Rahl’s Hessians, the highly touted heroes of the Battle of White Plains (October 28, 1776), and killed Rahl. The positioning and defense of the string of New Jersey posts were Cornwallis’s responsibility. Like most other observers, after the debacle of the New York campaign, the general believed the American army was on its last legs. Angry that the first decisive Patriot victory of the war had come against part of his own command, Cornwallis set out to catch and destroy Washington. His disposition was not helped by the cancellation of his scheduled leave to visit England, brought about by the Hessian humiliation.

American Perspective: After the Battle at Trenton, George Washington crossed back to the west bank of the Delaware River to rest and re-supply his men. Opportunities against Cornwallis’s scattered New Jersey outposts beckoned the aggressive Virginia commander. General Cadwalader’s 1,200 men had reached the eastern shore on December 27 and were still there below Trenton. Cadwalader urged Washington to return and take the offensive. With many enlistments set to expire at midnight on December 31 (the American army at the beginning of 1777 numbered just 1,600 Continentals), Washington authorized an illegal $10.00 bounty to keep hundreds of men in the ranks for another six weeks. Reinforcements from Philadelphia (about 500 newly raised militia under Brig. Gen. Thomas Mifflin) were also marching his way. On December 30, Washington crossed back to the east side of the river and marched his tired men to Trenton, where he ordered Cadwalader and Mifflin to join him.

Battle of Princeton Facts: The Fighting

Cornwallis awoke on January 3 to two unpleasant facts: his opponent had slipped away during the night, and artillery and small arms fire could clearly be heard in the direction of Princeton. Messengers soon arrived with word that Washington was assaulting Mawhood. Exactly what went through Cornwallis’s mind when he realized he had been utterly outgeneraled will never be known, but the realization could not have pleased him. With the commendable speed that was always his trademark, Cornwallis drove his army rapidly northeast to catch the Patriots between his own and Mawhood’s men.

The fighting he heard was the heavy rattle of musketry and artillery fire of Mawhood’s infantry, and a Patriot militia force sprinkled with Continentals in and around an orchard south of the Post Road one and one-half miles west of Princeton. Unbeknownst to Washington, Cornwallis had ordered Colonel Mawhood to send 800 of his men to Trenton that morning. Had Washington been thirty minutes later, he would have missed his objective entirely. As he drew near Stony Creek, Mawhood spotted General Mercer’s column to the south marching northeast toward the bridge to take up his blocking position. For reasons still unclear, both commands changed the direction of their march, Mawhood’s to the southeast and Mercer’s to the northeast. The opponents made a dash for a large orchard, which Mercer’s men reached first, leaving the British to form in an open field on the slightly lower ground between the Post and Back roads. Much of the 55th Regiment of Foot ended up on a patch of high ground farther to the east and did not play a significant role in the fighting. The frost-laden fields made it easy to spot the bright scarlet uniforms worn by Mawhood’s 17th and 55th infantry regiments. (The 40th had been left behind to guard Princeton.)

Both sides deployed quickly into line and began killing one another at a range of only 50 yards while unlimbering a pair of field pieces each. The British were fresh and alert, while the Patriots had marched all night in freezing temperatures. After one volley, Mawhood ordered a bayonet charge. Mercer was fighting on foot after his horse was injured and was mortally wounded in a melee that left him with at least seven stab wounds. Unable to withstand British steel, the militia retreated south toward the Back Road. When Mawhood spotted the head of another Patriot column arriving on the field behind Mercer’s men, he fell back and took up a defensive position. The men Mawhood spotted belonged to Cadwalader, who tried to engage the British infantry with militia in the open, failed, and began falling back in disorder. Thus far, the Princeton fight was not going well for the Patriots.

As if by script, Washington arrived on the scene. The general had been riding toward Princeton with Sullivan’s division on Back Road when he heard the heavy firing. He and a few aides rode cross-country to evaluate its significance. Washington rode in the midst of the disorganized militia, encouraging them to stand firm, align themselves, and fight the enemy. He did so with only 30 yards separating himself and the British front rank. Luckily for Washington, additional reinforcements from Sullivan’s command in the form of Rhode Island Continentals from Col. David Hitchcock’s brigade, Hand’s experienced Pennsylvanians, and Virginians under Scott had trotted across the same fields to throw back Mawhood’s advance. The presence of these veterans helped the militia remain in line, as did a pair of Patriot artillery pieces that had been firing since nearly the beginning of the action.

The combined Patriot attack triggered an intense firefight at close range that nearly enveloped Mawhood’s infantry (the 17th and part of the 55th) before breaking apart its cohesion; some scattered in the direction of New Brunswick, while others, Mawhood with them, broke through the lines and headed for the bridge and Trenton. The Americans gave chase and secured 50 prisoners before Washington recalled his men and continued advancing toward Princeton. The British 17th Regiment had performed the bulk of the fighting and suffered the vast majority of the casualties. The entire action consumed less than one hour.

The “battle” that followed was anti-climactic. The main Patriot army flooded into the area to find about 200 enemy soldiers, most from the 40th Regiment and a few from the 55th, barricaded inside Nassau Hall, a thickly walled building that served as the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University). A single round from one of Capt. Alexander Hamilton’s field pieces brought about their surrender. Princeton belonged to the Patriots.

Washington had no desire to hold the town, and indeed, his army was too weak and too exhausted to do so. His goal had been to launch another surprise attack against a New Jersey outpost. The rout of Mawhood and the capture of Princeton accomplished his goal. His additional dream of marching eighteen miles northeast to capture the enemy supply depot at New Brunswick was beyond his reach. The Patriot infantry were freezing, exhausted after forty hours of marching and fighting on slim rations. Many were already dropping to the ground to sleep. Knowing Cornwallis would even now be marching quickly in his direction, Washington ordered his men to secure food, supplies, and equipment, round up their prisoners, and move with as much haste as possible to the American base in the wooded hills at Morristown, New Jersey.

To learn more about the Battle of Princeton, read the Guide to the Battles of the American Revolution written by Theodore Savas and J. David Dameron.

Battle of Princeton Facts: Online Resources

- Wikipedia - Battle of Princeton

- Princeton Battlefield State Park

- Guide to the Battles of the American Revolution

- Library of Congress Collection of Revolutionary War Maps

- West Point Battle Maps of the American Revolution

- Journal of the American Revolution

- DIY Genealogy – Finding your Revolutionary War Ancestor

- The History Junkie’s Guide to the American Revolutionary War

- The History Junkie’s Guide to American Revolutionary War Battles

- The History Junkie’s Guide to the American Revolutionary War Timeline

- The History Junkie’s Guide to the 13 Original Colonies