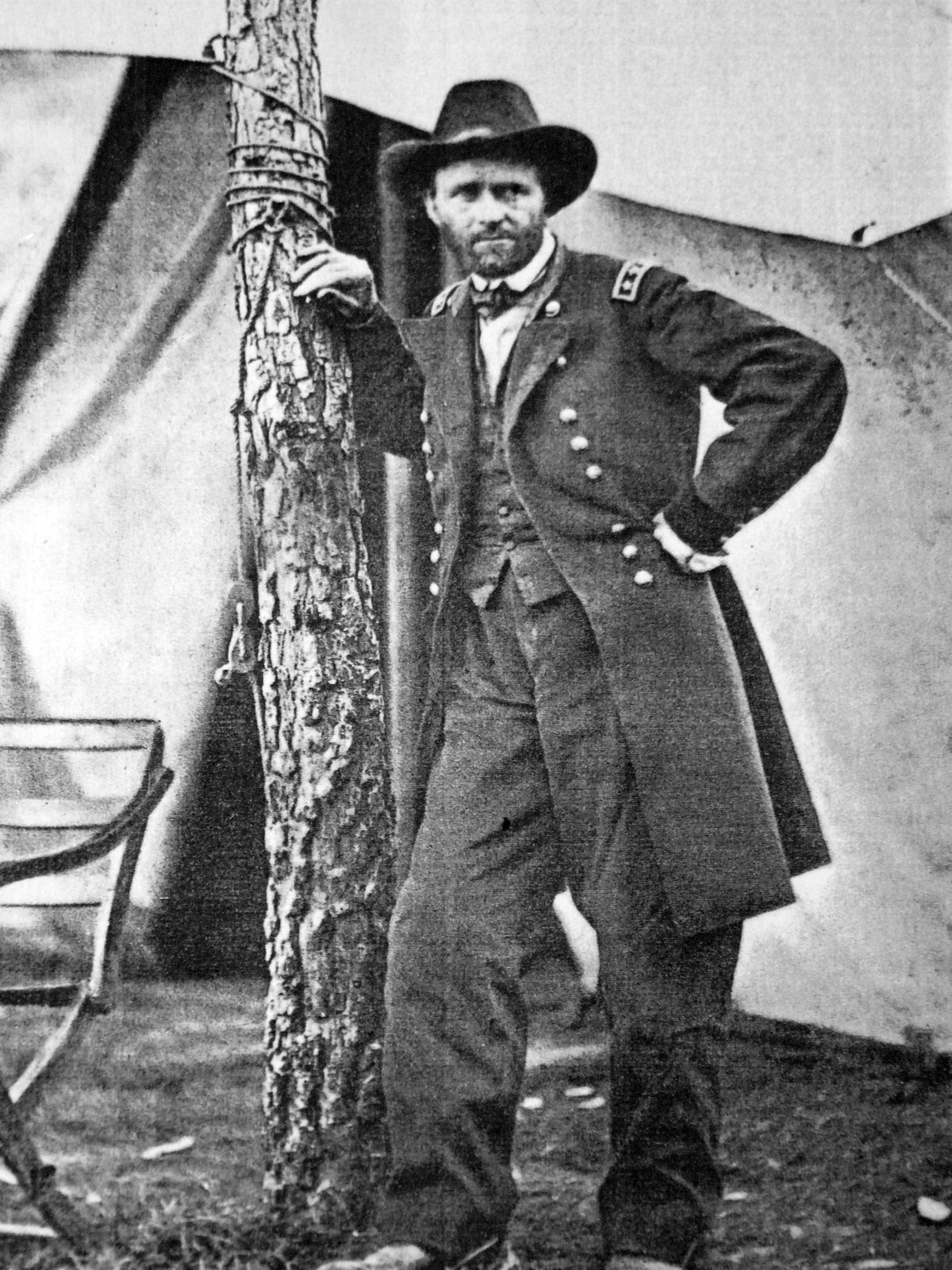

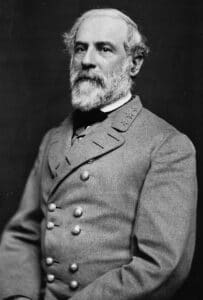

The Battle of the Wilderness was a savage battle during the American Civil War, fought May 5–7, 1864, between the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia under General Robert E. Lee and the Union Army of the Potomac under newly assigned Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant.

Although a tactical victory for Lee, the battle was the beginning of a period of attrition against the Confederates, which would only end just under a year later at Appomattox.

Prelude to Battle

Near dawn on May 4, 1864, the leading division of the Army of the Potomac reached Germanna Ford, 18 miles west of Fredericksburg. The spring campaign was underway, and it superficially mirrored the strategic situation prior to the battles of Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville.

A numerically superior Union force, well-supplied, in good spirits, and led by a new commander, moved south toward the Confederate capital. There, however, the similarities ended.

Ulysses S. Grant now directed the Army of the Potomac, although George Meade technically retained the authority he had inherited from Hooker just before the Battle of Gettysburg.

In fact, Grant carried the new rank of lieutenant-general and bore responsibility for all Federal armies, but unlike some of his predecessors, his headquarters was in the field. And it was in the field that the General-in-chief told Meade, "Lee's army will be your objective. Where he goes, there you will go also."

The Confederates also entered the 1864 campaign brimming with optimism and anxious to avenge their defeat at Gettysburg. As usual, the 62,000-man Army of Northern Virginia found itself vastly outgunned and scrambling for supplies, but based on past experience, these handicaps posed little concern.

Confederate generalship in the post-Jackson era created more serious problems. Lee elevated both A. P. Hill and Richard S. Ewell to corps command following Jackson's death, but neither officer performed particularly well. Only James Longstreet provided Lee with experienced leadership at the highest army level.

Grant also reorganized his forces, consolidating the army into three corps led by Major Generals Gouverneur K. Warren, John Sedgwick, and Winfield Scott Hancock. Ambrose Burnside's independent Ninth Corps raised the total Union complement to 120,000 men.

The Bluecoats negotiated the Rapidan River on May 4. Lee easily spotted the Federal advance from his signal stations, and he immediately ordered his forces to march east and strike their opponents in the familiar and foreboding Wilderness, where Grant's legions would be neutralized by the inhospitable terrain. Ewell moved via the Orange Turnpike, and Hill utilized the parallel Orange Plank Road to the south.

Longstreet's corps faced a longer trek than did its comrades, so Lee advised Ewell and Hill to avoid a general engagement until Longstreet could join them.

The Fighting

Grant, although anxious to confront Lee at the earliest good opportunity, preferred not to fight in the green hell of the Wilderness. On the morning of May 5, he directed his columns to push southeast through the tangled jungle and into open ground. Word arrived, however, that an unidentified body of Confederates approaching from the west on the turnpike threatened the security of his advance, causing Warren to dispatch a division to investigate the report.

The Confederates, of course, proved to be Ewell's entire corps. About noon, Warren's lead regiments discovered Ewell's position on the west edge of a clearing called Saunders Field and received an ungracious greeting. "The very moment we appeared," testified an officer in the 140th New York, "[they] gave us a volley at long range, but evidently with a very deliberate aim and with serious effect." The Battle of the Wilderness had begun.

Warren hustled additional troops toward Saunders Field from his headquarters at the Lacy House and attacked a front more than a mile wide, overlapping both ends of the clearing. The fighting ebbed and flowed, often dissolving into isolated combat between small units confused by the bewildering forest, "bushwhacking on a grand scale," one participant called it. By nightfall, a deadly stalemate settled over the Turnpike.

Three miles south along the Plank Road, another battle raged unrelated to the action on Ewell's front. Two of A.P. Hill's divisions pressed east toward the primary north-south avenue through the Wilderness, the Brock Road. If they could seize this intersection quickly, they would isolate Hancock's corps, south of the Plank Road, from the rest of the Union army.

Grant recognized the peril and hurried one of Sedgwick's divisions to the vital crossroads. These men arrived just in time and, in cooperation with Hancock, slowly began to drive Hill's overmatched brigades west through the forest. Fortunately for the Confederates, darkness closed the fighting for the day.

Lee expected Longstreet's corps to relieve Hill on the Plank Road that night. Hill, anticipating Longstreet's arrival, refused to redeploy his exhausted troops to meet renewed attacks in the morning, which would prove nearly disastrous. For a variety of reasons, Longstreet had fallen hours behind schedule. Hancock's 5:00 a.m. offensive on May 6, therefore, pitted 23,000 Federals against only Hill's unprepared divisions and overwhelmed them.

A single line of Southern artillery, posted on the western edge of the Widow Tapp's Farm, now provided the sole opposition to Hancock's surging masses. The guns could not survive long unsupported by infantry.

Just then, a ragged line of soldiers emerged from the forest to the west. "What brigade is this?" inquired Lee. "The Texas brigade!" came the response. Lee knew the only Texans in his army belonged to the First Corps under Longstreet. These troops, along with others from Arkansas, Georgia, and Alabama, charged the blue ranks before them and halted Hancock's advance at the price of 50 percent casualties in several regiments.

Longstreet took this chance to snatch the initiative. Utilizing the unfinished railroad (the same corridor on which Sickles had captured the Georgians at Chancellorsville), four Confederate brigades crept astride the Union left flank. The Southerners poured through the woods, rolling up Hancock's unwary troops "like a wet blanket."

Union General James Wadsworth fell mortally wounded, and the Federals streamed back toward the Brock Road as Longstreet trotted eastward on the Plank Road in the wake of this splendid achievement, intent upon pursuing the shaken Federals and throwing a knockout punch at his staggered opponents. Then shots rang out from south of the road. Longstreet reeled in his saddle, the victim of a volley fired by Confederate troops about five miles from where Jackson had met the same improbable fate the year before.

Unlike Jackson, Longstreet would survive his wound, but the tragedy arrested the Rebels' impetus. Lee personally directed a resumption of the offensive a few hours later and briefly managed to puncture the Federal lines along the Brock Road. Hancock, however, expelled the intruders from his midst and maintained his position by the narrowest of margins.

Fighting along the Turnpike on May 6 had also been vicious if indecisive. Late in the day, Georgia Brigadier General John B. Gordon received permission to assault Grant's unprotected right flank. Gordon struck near sunset, capturing two Union generals and routing the Federals. The effort began too late to exploit Gordon's success, however, and Grant reformed his battered brigades in the darkness.

Both armies expected more combat on May 7, but neither side initiated hostilities. Fires blazed through the forest, sending hot, acrid smoke rolling into the air and searing the wounded trapped between the lines - a fitting conclusion to a grisly engagement.

Conclusion

The Battle of the Wilderness marked another tactical Confederate victory. Grant watched both of his flanks crumble on May 6 and lost more than twice as many soldiers (about 18,000 to 8,000) as Lee. Veterans of the Army of the Potomac had seen this before: cross the river, get whipped, retreat, the story of Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville reprised, and Grant would be referred to once more as a "butcher" in the papers for the large number of men he had lost in the battle.

But Grant was also something that previous commanders of the Army of the Potomac were not, and Lee had already sensed it long before the Wilderness: Grant was a fighting general who wouldn't give up. Late on May 7, Grant rode at the head of his army and approached a lonely junction in the Wilderness.

A left turn would take his army back toward the fords of the Rapidan and Rappahannock and retreat. To the right lay the highway to Richmond via Spotsylvania Court House.

Grant went to the right to the cheers of his soldiers.

This marked the first time that Grant and Lee had met each other in battle. Grant understood what the generals before him did not, and that is, he had superior resources, and Lee did not. Grant could replace his losses, while Lee's 8,000 men lost were harder to come by.

Grant's relentlessness would lead to Appomattox.