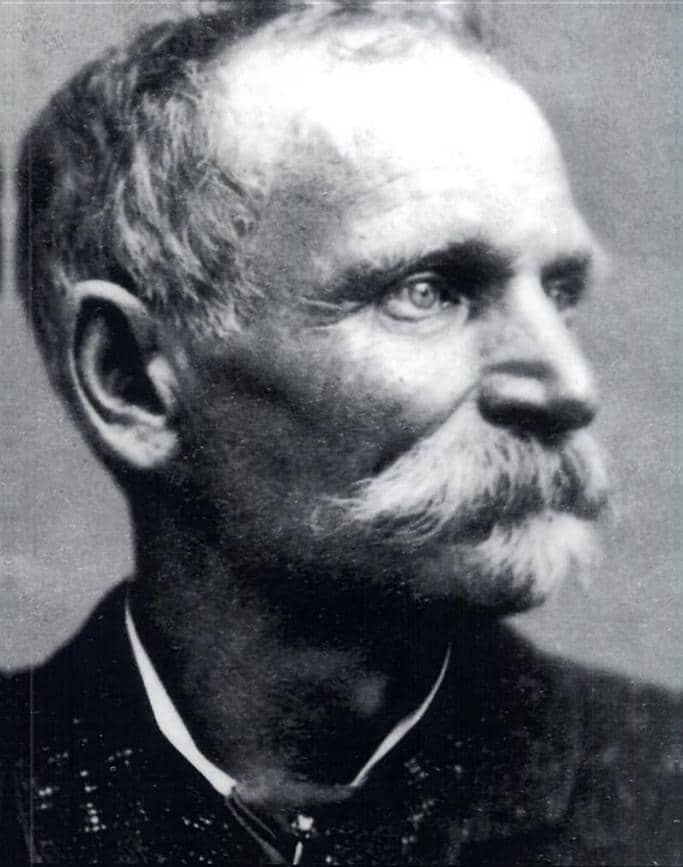

Black Bart, whose real name is Charles Earl Boles, was a famous gunslinger of the Wild West who became known for his prolific crime spree and the poetic messages he left behind after two of his robberies.

While many Wild West outlaws had a rough reputation, Black Bart was known as a gentleman bandit due to his flair and style. He would become one of the most notorious stagecoach robbers in American History.

His base of operations was around the border of California and Oregon during the 1870s and 1880s.

Early Life

Black Bart was born across the Atlantic Ocean in Norfolk, England, to John and Maria Boles. He was the third child out of ten in his family.

His parents immigrated from England to New York and purchased a farm.

California Gold Rush: When Black Bart was around 20 years old, the United States was experiencing a wave of migration from the East to the West due to the California Gold Rush. He and his brothers caught the itch and went west to pursue the wealth that was being told about.

The brothers returned home in 1852, and shortly after their return, both of his brothers became sick and died. Black Bart returned to California for another two years.

Black Bart married Mary Elizabeth Johnson in 1854, and the two resided in Decatur, Illinois, and had four children.

Civil War: In 1861, America was thrown into the Civil War. Charles "Black Bart" Boles enlisted as a private in Company B, 116th Illinois Regiment of the Union Army on August 13, 1862. He served valiantly and was wounded during the Battle of Vicksburg and would take part when General William Sherman marched to the sea.

He received brevet commissions as both second lieutenant and first lieutenant and, at the end of the war, was discharged with his regiment in Washington, D.C..

He returned to his family in Illinois.

In 1867, Boles went prospecting for gold in Idaho and Montana. In a surviving letter to his wife from August 1871, he told her of an unpleasant encounter with some Wells Fargo & Company agents and vowed to exact revenge.

His wife never heard from him again, and in time, she presumed he had died

Life as a Criminal

Black Bart had not died but opted to turn to crime to claim his fortune.

He began to go by Black Bart to give himself a new identity and then proceeded to rob stagecoaches. He robbed a Wells Fargo stagecoach 28 times around northern California between 1875 - 1883. During these robberies, he left two poems, and despite it only happening twice, the poems would become known as his signature.

Regardless of his signature, he became wealthy by making a fortune off of his robberies.

He did all of this despite being afraid of horses. All of his robberies were on foot, and it was said that he never fired a weapon.

He became known as a gentleman due to his polite demeanor, his lack of cursing, and the way he dressed.

First Robbery: On July 26, 1875, Black Bart robbed his first stagecoach in Calaveras County, California. During the robbery, he politely ordered the stage driver, John Shine, to "throw down the box." As Shine handed over the strongbox, Black Bart shouted, "If he dares to shoot, give him a solid volley, boys!". Seeing rifle barrels pointed at him from the nearby bushes, Shine quickly handed over the strongbox. Shine waited until Boles vanished and then went to recover the empty strongbox, but upon examining the area, he discovered that the "men with rifles" were actually carefully rigged sticks. Black Bart's first robbery netted him $160.

Last Robbery: His last holdup took place on November 3, 1883, at the site of his first robbery on Funk Hill, southeast of the present town of Copperopolis. Driven by Reason McConnell, the stage had crossed the Reynolds Ferry on the old road from Sonora to Milton.

The driver stopped at the ferry to pick up Jimmy Rolleri, the 19-year-old son of the ferry owner. Rolleri had his rifle with him and got off at the bottom of the hill to hunt along the creek and meet the stage on the other side.

When he arrived at the western end, he found that the stage was not there and began walking up the stage road. Near the summit, he saw the stage driver and his team of horses.

McConnell told him that as the stage had approached the summit, Black Bart had stepped out from behind a rock with a shotgun in his hands. He forced McConnell to unhitch the team and take them over the crest of the hill.

Bart then tried to remove the strongbox from the stage, but it had been bolted to the floor and took Boles some time to remove. Rolleri and McConnell went over the crest and saw Bart backing out of the stage with the strongbox.

McConnell grabbed Rolleri's rifle and fired at Black Bart twice but missed. Rolleri took the rifle and fired as Bart entered a thicket. He stumbled as if he had been hit. Running to the thicket, they found a small, blood-stained bundle of mail he had dropped.

Bart had been wounded in the hand. After running a quarter of a mile, he stopped and wrapped a handkerchief around his hand to control the bleeding. He found a rotten log and stuffed the sack with the gold amalgam into it, keeping $500 in gold coins.

He hid the shotgun in a hollow tree, threw everything else away, and fled. In a manuscript written by stage driver McConnell about 20 years after the robbery, he claimed he fired all four shots at the outlaw. The first missed, but he thought the second or third shot hit Bart and was sure the fourth did. Black Bart only had one wound on his hand.

Arrest: After being wounded and leaving the scene of the crime, Black Bart left behind many personal items that could be linked back to him. Wells Fargo Detective James B. Hume found these belongings at the scene and began an investigation to convict Black Bart.

The main piece of evidence that Hume used was a handkerchief with a laundry mark F.X.O.7. Hume contacted every laundry in San Francisco and asked them about the mark. After visiting almost 90 laundries, he traced the mark to Ferguson & Bigg's California Laundry. He learned that the handkerchief belonged to a man who lived in a modest boarding house.

Black Bart had taken on an identity as a mining engineer, which allowed him the cover to take frequent "business trips." After looking into these so-called "trips," Hume saw that they coincided with the Wells Fargo robberies.

Black Bart was confronted about the robberies and initially denied them, saying that he was not Black Bart. Eventually, he confessed only to crimes before 1879 since he believed the statute of limitations had expired on those robberies.

He was booked and given the name T.Z. Spalding, but after the police investigated his home, they found a Bible gifted to him from his wife that had his real name in it.

Black Bart, AKA Charles Earl Boles, was finally put into prison.

A policeman had this to say about him:

a person of great endurance. Exhibited genuine wit under most trying circumstances and was extremely proper and polite in behavior. Eschews profanity.

Bart was only convicted of the final robbery and was sentenced to 6 years and released after 4 due to good behavior. He never robbed a stagecoach again.

He did write to his wife before his death, saying he was tired of being shadowed by Wells Fargo.

It is believed he died in February 1888.

List of Crimes by Black Bart

The 1870s

July 26, 1875: The stage from Sonora, Tuolumne County, to Milton, Calaveras County, was robbed by a man wearing a flour sack over his head with two holes cut out for the eyes.

December 28, 1875: The stage from North San Juan, Nevada County, to Marysville, Yuba County. A newspaper related that it was held up by four men. This, too, had a description of the lone robber and his "trademarks." The "three other men" were in the hills around the stage; the driver saw their "rifles." When the investigators arrived at the scene, they found the "rifles" used in the heist were nothing more than sticks wedged in the brush.

August 3, 1877: The stage from Point Arena, Mendocino County, to Duncans Mills, Sonoma County.

July 25, 1878: A stage traveling from Quincy, Plumas County, to Oroville, Butte County.

October 2, 1878: In Mendocino County, near Ukiah, Bart was seen picnicking along the roadside before the robbery.

October 3, 1878: In Mendocino County, the stage from Covelo to Ukiah was robbed. Bart walked to the McCreary farm and paid for dinner. Fourteen-year-old Donna McCreary provided the first detailed description of Bart: "Graying brown hair, missing two of his front teeth, deep-set piercing blue eyes under heavy eyebrows. Slender hands and intellectual in conversation, well-flavored with polite jokes."

June 21, 1879: The stage from La Porte, Plumas County, to Oroville, Butte County. Bart said to the driver, "Sure hope you have a lot of gold in that strongbox; I'm nearly out of money." In fact, the stage held no Wells Fargo gold or cash.

October 25, 1879: An interstate route was robbed when Bart held up the stage from Roseburg, Douglas County, Oregon, to Redding, Shasta County, California, stealing U.S. mail pouches on a Saturday night.

October 27, 1879: Another California robbery, the stage from Alturas, Modoc County, to Redding, Shasta County. Jim Hume was sure that Bart was the one-eyed ex-Ohioan Frank Fox.

The 1880s

July 22, 1880: In Sonoma County, the stage from Point Arena to Duncans Mills.

September 1, 1880: In Shasta County, the stage from Weaverville to Redding. Near French Gulch, Bart said, "Hurry up the hounds; it gets lonesome in the mountains."

September 16, 1880: In Jackson County, Oregon, the stage from Roseburg to Yreka, California. This is the farthest north Bart is known to have robbed.

September 23, 1880: In Jackson County, Oregon, the stage from Yreka to Roseburg (President Rutherford B. Hayes and General William T. Sherman traveled on this stage three days later). On October 1, a person (Frank Fox?) who closely matched the description of Bart was arrested at Elk Creek Station and later released.

November 20, 1880: In Siskiyou County, the stage from Redding to Roseburg. This robbery failed because of the noise of an approaching stage or because of a hatchet in the driver's hand.

August 31, 1881: In Siskiyou County, the stage from Roseburg to Yreka. Mail sacks were cut in a "T" shape, another Bart trademark.

October 8, 1881: In Shasta County, the stage from Yreka to Redding. Stage driver Horace Williams asked Bart, "How much did you make?" Bart answered, "Not very much for the chances I take."

October 11, 1881: In Shasta County, the stage from Lakeview to Redding. Hume kept losing Bart's trail.

December 15, 1881: In Yuba County, near Marysville. Bart took mailbags and evaded capture due to his swiftness afoot.

December 27, 1881: In Nevada County, the stage from North San Juan to Smartsville. Nothing much was taken, but Bart was wrongly blamed for another stage robbery in Smartsville.

January 26, 1882: In Mendocino County, the stage from Ukiah to Cloverdale. Again, the posse was on his tracks within the hour, and again, they lost him after Kelseyville.

June 14, 1882: In Mendocino County, the stage from Little Lake to Ukiah. Hiram Willits, Postmaster of Willitsville (present-day Willits, California), was on the stage.

July 13, 1882: In Plumas County, the stage from La Porte to Oroville. This stage was loaded with gold, and George Hackett was armed. Bart lost his derby as he fled the scene when it was determined that the Wells Fargo agent in LaPorte had supplied hardware to bolt down the strongbox. His derby was traced to him eventually through the laundry mark. The same stage was again held up in Forbestown, and Hackett blasted the would-be robber into the bushes. This was mistakenly blamed on Bart.

September 17, 1882: In Shasta County, the stage from Yreka to Redding was a repeat of October 8, 1881, but Bart got only a few dollars.

November 24, 1882: In Sonoma County, the stage from Lakeport to Cloverdale was "The longest 30 miles in the World."

April 12, 1883: In Sonoma County, the stage from Lakeport to Cloverdale was another repeat of the last robbery.

June 23, 1883: In Amador County, the stage from Jackson to Ione.

November 3, 1883: In Calaveras County, the stage from Sonora to Milton.