The Boston Massacre was a significant event in early American History.

While Boston had already become a hotbed of conflict for the British, it was growing more tense and would eventually lead to the Boston Massacre and, later, the Boston Tea Party.

It seemed as though every move the British made to try and quench the emotions of the colonists was a wrong move that only escalated them and played into the hands of those pushing propaganda.

Jump to:

- 1. The Townshend Acts Caused The Uproar In Boston

- 2. The Presence of British Soldiers Caused Escalation

- 3. A Murder Had Already Occurred That Alarmed Boston

- 4. The Boston Massacre Occurred Due to a 13 Year Old Boy

- 5. A Young Henry Knox Tried To Calm The Situation

- 6. The Crowd's Actions Caused Fear and Chaos Within The British Soldiers

- 7. 11 Men Were Hit By Musket Balls

- 8. The British Troops Were Ordered Out Of The Province

- 9. Paul Revere Helped Push An Inflammatory Narrative

- 10. Two Future Signers of the Declaration of Independence Opposed Each Other At Trial

- 11. The British Soldiers Were Found Not Guilty

- 12. Crispus Attucks Was Used as Propaganda During the Civil War

After the trial ended, there were still many tensions that were bubbling on the surface.

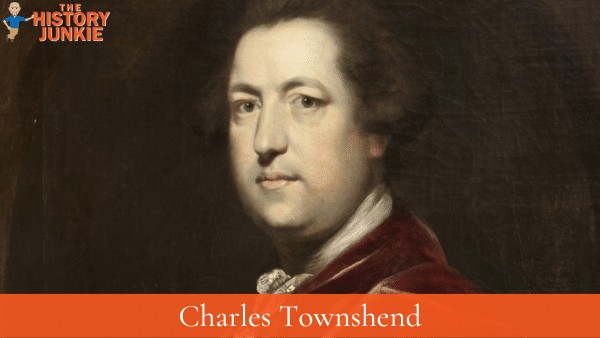

1. The Townshend Acts Caused The Uproar In Boston

Since the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the people of Boston had viewed themselves as somewhat autonomous. While they appreciated the backing of the British government and most viewed themselves as British subjects, there was also this idea of Massachusetts being this "City on a Hill."

Also Read: Famous Colonists in Colonial America

This idea was put forward by John Winthrop and carried on throughout the growth of the colony.

The French and Indian War would bring colonists into a conflict with the French, and they proudly served their mother country and defended the land against the French and natives.

After the war, the British accrued much debt and looked for ways of increasing revenue. They began to enact various acts, which were met with pushback from all the colonies, but especially Massachusetts.

The Townshend Acts were put in place after other acts had failed. This resulted in an escalation of emotion, and groups such as the Sons of Liberty saw it as an opportunity to gain more support for their cause.

The escalation would end in shots fired and the eventual repeal of the Townshend Acts.

2. The Presence of British Soldiers Caused Escalation

After fighting a war for England, the colonists were gifted with new taxes and the presence of British troops to enforce them. This was seen as an insult, but it was more than just that.

Many of the citizens of Boston were ropemakers, shipbuilders, and commercial fishermen. Industry within Boston was tied to the ocean and shipbuilding.

This led to the creation of many jobs, including jobs for runaway slaves and new immigrants who were willing to take on these dangerous endeavors on the ocean.

Also Read: Facts About Colonial America

This also became a great way for British soldiers to moonlight as fishermen, which would hurt locals who depended on those jobs to earn a livable wage for their families.

The moonlighting of British soldiers would be a direct reason that Crispus Attucks would become angry and march into the town square to protest the British presence in the colony.

3. A Murder Had Already Occurred That Alarmed Boston

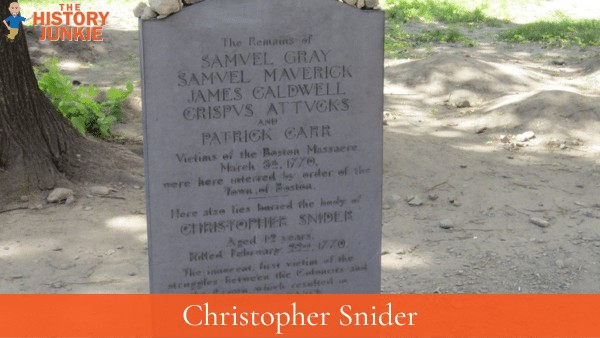

Christopher Snider, an 11-year-old boy, was shot and killed by customs officer Ebenezer Richardson in Boston on February 22, 1770.

His death is considered to be the first American casualty of the American Revolution.

On February 22, 1770, he joined a crowd outside the house of customs officer Ebenezer Richardson in the North End. Richardson had tried to disperse a protest in front of the shop of Loyalist Theophilus Lillie.

The crowd threw stones that broke Lillie's windows and struck his wife. Richardson fired a gun into the crowd, killing Seider and wounding another boy.

Snider's death was a major turning point in the lead-up to the American Revolution. His funeral was a massive public event attended by over 2,000 people.

It was seen as a symbol of the colonists' resistance to British rule. Richardson was convicted of murder, but he was pardoned by the king and reinstated in his position as a customs officer.

This further inflamed tensions between the colonists and the British government.

4. The Boston Massacre Occurred Due to a 13 Year Old Boy

On the evening of March 5, 1770, Private Hugh White was standing on guard duty outside the Boston Customs House.

A 13-year-old wigmaker's apprentice named Edward Garrick approached him and accused Captain-Lieutenant John Goldfinch of refusing to pay a bill due to Garrick's master. Goldfinch had actually settled the account the previous day, but he ignored the insult.

White told Garrick to be more respectful of the officer, but Garrick continued to taunt him. He even started poking Goldfinch in the chest with his finger.

White finally lost his patience and left his post to challenge the boy. He struck Garrick on the side of the head with his musket, causing him to cry out in pain.

Garrick's companion, Bartholomew Broaders, began to argue with White, which attracted a larger crowd.

Within a short period of time, the situation became increasingly hostile.

5. A Young Henry Knox Tried To Calm The Situation

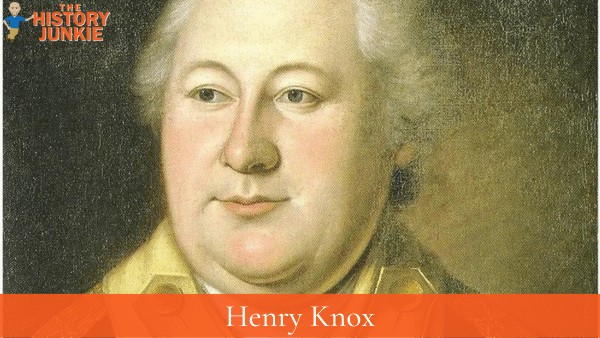

Henry Knox, a 19-year-old bookseller who later served as a general in the American Revolution, came upon the scene and warned Private Hugh White that if he fired his musket, he would be killed.

The crowd around White had grown larger and more boisterous as the evening progressed. Church bells were rung, which usually signified a fire, bringing more people out.

More than 50 Bostonians pressed around White, led by a mixed-race former slave named Crispus Attucks, throwing objects at the sentry and challenging him to fire his weapon. White had taken up a somewhat safer position on the steps of the Custom House, and he sought assistance.

Runners alerted Captain Thomas Preston, the officer of the watch at the nearby barracks. Preston dispatched a non-commissioned officer and six privates from the grenadier company of the 29th Regiment of Foot to relieve White with fixed bayonets.

The soldiers pushed their way through the crowd. Knox took Preston by the coat and told him, "For God's sake, take care of your men. If they fire, you must die." Preston responded, "I am aware of it."

When they reached Private White on the custom house stairs, the soldiers loaded their muskets and arrayed themselves in a semicircular formation.

Preston shouted at the crowd, estimated between 300 and 400, to disperse.

6. The Crowd's Actions Caused Fear and Chaos Within The British Soldiers

The crowd continued to taunt the soldiers, yelling "Fire!", spitting at them, and throwing snowballs and other small objects. Innkeeper Richard Palmes approached the soldiers carrying a cudgel. He asked Captain Preston if the soldiers' weapons were loaded.

Preston assured him that they were but that they would not fire unless he ordered it. He later stated in his deposition that he was unlikely to do so since he was standing in front of them.

A thrown object struck Private Montgomery, knocking him down and causing him to drop his musket. He recovered his weapon and angrily shouted, "Damn you, fire!", then discharged it into the crowd, although no command was given.

Palmes swung his cudgel first at Montgomery, hitting his arm, and then at Preston. He narrowly missed Preston's head, striking him on the arm instead.

There was a pause of uncertain length (eyewitness estimates ranged from several seconds to two minutes), after which the soldiers fired into the crowd. It was not a disciplined volley since Preston gave no orders to fire.

7. 11 Men Were Hit By Musket Balls

The soldiers fired a ragged series of shots, hitting 11 people.

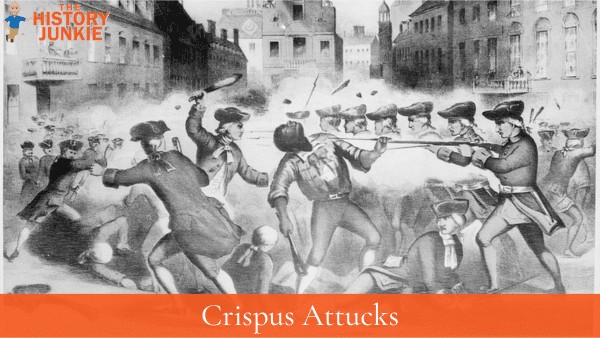

Three Americans died instantly: rope maker Samuel Gray, mariner James Caldwell, and Crispus Attucks, a mixed-race former slave.

Seventeen-year-old apprentice ivory turner Samuel Maverick was struck by a ricocheting musket ball and died early the next morning.

Irish immigrant Patrick Carr was shot in the abdomen and died two weeks later.

Apprentice Christopher Monk was seriously wounded and crippled and died in 1780, purportedly due to the injuries that he had sustained in the attack a decade earlier.

Governor Thomas Hutchinson was brought to the scene, and he was able to calm the crowd from the balcony by promising a full investigation.

8. The British Troops Were Ordered Out Of The Province

After the Boston Massacre, the British leadership was placed in a tough situation. The presence of the troops after the deaths of Bostonians did more harm than good, and there was a genuine fear for their life.

Captain Preston and his men were arrested the following day, but that did not do enough to quell the emotions.

General Thomas Gage quickly realized the situation and removed the 29th Regiment from Massachusetts Bay.

Governor Hutchinson took advantage of the changes to delay the trial in order for emotions to calm so that a fair trial could be tried.

9. Paul Revere Helped Push An Inflammatory Narrative

A media battle ensued after the Boston Massacre.

Henry Pelham drew an illustration that was published that depicted the British as guilty of murder and tyranny. Paul Revere then recreated the same image and made it more graphic with color.

In the image above, it is clear that Captain Thomas Preston is being portrayed as ordering the soldiers to fire in an orderly fashion into the crowd. This did not happen.

The image above also shows the three that died instantly, including Crispus Attucks. Paul Revere's illustration clearly shows an African American, while the original does not.

This propaganda incited the city and made it difficult for the British sentries to receive a fair trial since it had been seen by most Bostonians.

Those loyal to the Crown also pushed their side of the story, but it was not as influential as the Sons of Liberty.

10. Two Future Signers of the Declaration of Independence Opposed Each Other At Trial

Finding representation for the British soldiers at the Boston Massacre Trial was near impossible.

The Sons of Liberty intimidated many Bostonians, and the fact that Great Britain had made an unpopular decision of putting British soldiers into Boston to enforce the Townshend Acts made the soldiers unsympathetic characters.

Even if the colonists believe the treatment of them was unjust, they did not care what occurred because they were beginning to despise England.

Robert Treat Paine was put in charge of the prosecution. He would go on to serve in the Continental Congress later.

The defense was argued by John Adams, who was the cousin of Samuel Adams. His relation to Samuel probably aided in him not being easily intimidated. He had also spoken against the Stamp Act in previous years.

Each man would come into the court as opposing counsel but, five years later, would be arguing for independence from Great Britain.

11. The British Soldiers Were Found Not Guilty

The trial of the eight other soldiers opened on November 27, 1770. Adams told the jury to look beyond the fact that the soldiers were British.

Also Read: Boston Massacre Trial

He referred to the crowd that had provoked the soldiers as "a motley rabble of saucy boys, negroes, and molattoes, Irish teagues and outlandish Jack Tarrs" (sailors).

He then stated, "And why we should scruple to call such a set of people a mob, I can't conceive unless the name is too respectable for them.

The sun is not about to stand still or go out, nor the rivers to dry up because there was a mob in Boston on the 5th of March that attacked a party of soldiers."

Adams also described the former slave Crispus Attucks, saying "his very look was enough to terrify any person" and that "with one hand [he] took hold of a bayonet, and with the other knocked the man down."

However, two witnesses contradict this statement, testifying that Attucks was 12–15 feet away from the soldiers when they began firing, too far away to take hold of a bayonet. Adams stated that it was Attucks' behavior that, "in all probability, the dreadful carnage of that night is chiefly to be ascribed."

He argued that the soldiers had the legal right to fight back against the mob, and so were innocent. If they were provoked but not endangered, he argued, they were at most guilty of manslaughter.

The jury agreed with Adams' arguments and acquitted six of the soldiers after two and a half hours of deliberation. Two of the soldiers were found guilty of manslaughter because there was overwhelming evidence that they had fired directly into the crowd.

The jury's decisions suggest that they believed that the soldiers had felt threatened by the crowd but should have delayed firing.

The convicted soldiers were granted reduced sentences by pleading benefit of clergy, which reduced their punishment from a death sentence to branding of the thumb in open court.

12. Crispus Attucks Was Used as Propaganda During the Civil War

The following years after the Boston Massacre occurred, Crispus Attucks's name faded from the history books. While he was certainly known at a local level, he did not gain national notoriety until the Civil War.

Black abolitionists rediscovered his story prior to the war and began to build monuments and dedicated days to his memory. He was used as propaganda and branded as a black man fighting for his independence.

Attucks was already free and had a vocation. He was most likely fighting against the British presence in Boston and that they took their jobs away. Him being a black man, he was most likely an easy target to lose employment.

Longfellow's poem would bring him national recognition.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was a famous American poet who wrote about many historical figures, including Crispus Attucks. In his poem "The Song of the American Revolution," Longfellow wrote:

Then shot the British soldier, and Crispus Attucks fell, The first martyr in the blood-red birth of Freedom's spell.

Longfellow's poem helped to immortalize Attucks as a symbol of the American Revolution and the fight for freedom. The poem also helped to raise awareness of Attucks' African American heritage, which was not widely known at the time.