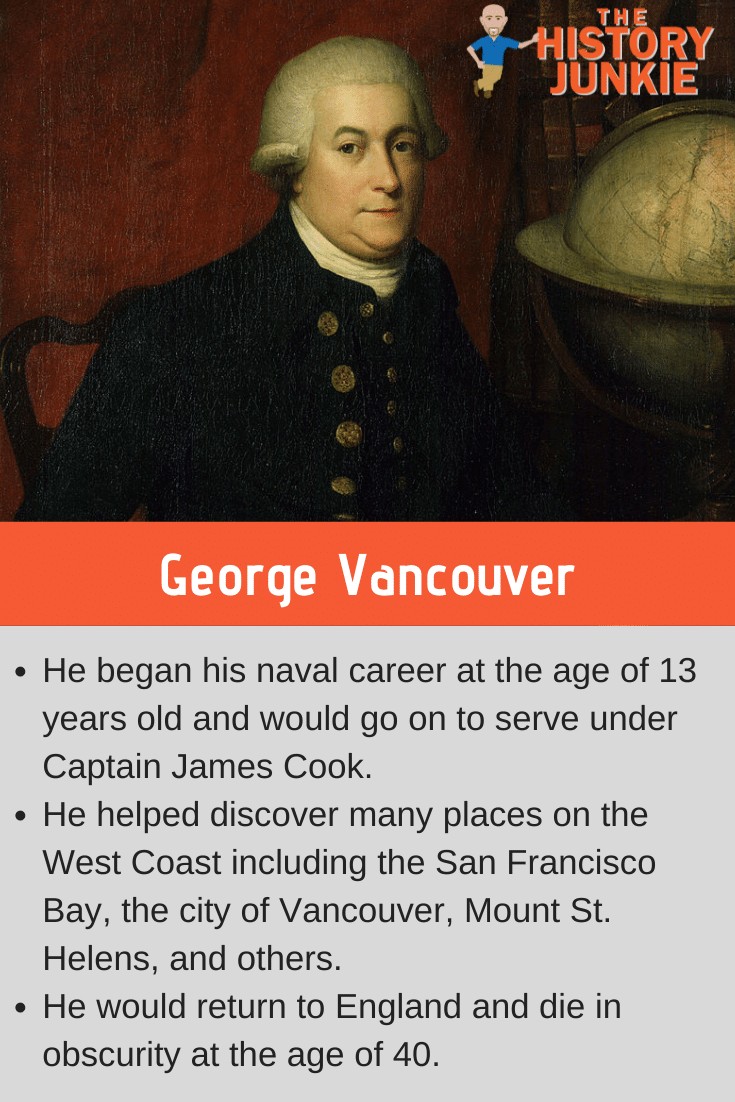

George Vancouver was a famous explorer from England who served in the British Royal Navy. Many of his discoveries occurred in the Pacific Ocean during or just prior to the American Revolutionary War.

There is a city that is named after him in Canada, and he was one of the first Europeans to interact with the Northwest Indian Tribes.

Early Life and Career

George Vancouver was born to John Jasper Vancouver and Bridget Berners on June 22, 1757. It was clear that he enjoyed the maritime vocation and quickly joined the Royal Navy in 1770.

The 1770s would begin with England being the unquestioned power in the world and would end with them trying to hang on to the 13 original colonies.

While much is studied about that location during this timeframe, the English Empire had expanded to become a global empire with colonies throughout the world and wanted to expand and discover more.

On his first mission, Vancouver would serve on a ship that was led by Captain James Cook, one of the greatest explorers in English history. It would be during this voyage that he would be among some of the first to see the coast of Australia. He served again with Cook and would first see the Hawaiian Islands.

As stated previously, Great Britain was involved in the American Revolution, and the British suffered a surprising defeat at the Battle of Saratoga. It was around this time that the Americans entered into the Franco-American Treaty with France.

Spain would also join the war on the American side, and both of these nations would begin to threaten the British. The war went from a local rebellion to a global conflict.

Vancouver did not see much action, but after the Treaty of Paris was reached, he was given control over his own ship, the HMS Discovery.

Voyages and Discoveries

Departing England with two ships, HMS Discovery, and HMS Chatham, on 1 April 1791, Vancouver commanded an expedition charged with exploring the Pacific region.

In its first year, the expedition traveled to Cape Town, Australia, New Zealand, Tahiti, and Hawaii, collecting botanical samples and surveying coastlines along the way.

He formally claimed Possession Point, King George Sound, Western Australia, now the town of Albany, Western Australia, for the British.

Proceeding to North America, Vancouver followed the coasts of present-day Oregon and Washington northward.

In April 1792, he encountered American Captain Robert Gray off the coast of Oregon just prior to Gray's sailing up the Columbia River.

Vancouver entered the Strait of Juan de Fuca, between Vancouver Island and the present-day Washington state mainland, on 29 April 1792. His orders included a survey of every inlet and outlet on the west coast of the mainland, all the way north to Alaska.

Most of this work was in small craft propelled by both sail and oar; maneuvering larger sail-powered vessels in uncharted waters was generally impractical and dangerous.

Vancouver named many features for his officers, friends, associates, and his ship Discovery, including:

- Mount Baker – after Discovery's 3rd Lieutenant Joseph Baker, the first on the expedition to spot it

- Mount St. Helens – after his friend, Alleyne Fitzherbert, 1st Baron St Helens

- Puget Sound – after Discovery's 2nd lieutenant Peter Puget,[8] who explored its southern reaches.

- Mount Rainier – after his friend, Rear Admiral Peter Rainier.

- Port Gardner and Port Susan, Washington – after his former commander, Vice Admiral Sir Alan Gardner, and his wife Susannah, Lady Gardner.

- Whidbey Island – after naval engineer Joseph Whidbey.

- Discovery Passage, Discovery Island, Discovery Bay, Port Discovery, and Discovery Park.

After a Spanish expedition in 1791, George Vancouver was the second European to enter Burrard Inlet on 13 June 1792, naming it for his friend Sir Harry Burrard. It is the present-day main harbour area of the City of Vancouver beyond Stanley Park.

He surveyed Howe Sound and Jervis Inlet over the next nine days. Then, on his 35th birthday on 22 June 1792, he returned to Point Grey, the present-day location of the University of British Columbia.

Here, he unexpectedly met a Spanish expedition led by Dionisio Alcalá Galiano and Cayetano Valdés y Flores.

Vancouver was "mortified" (his word) to learn they already had a crude chart of the Strait of Georgia based on the 1791 exploratory voyage of José María Narváez the year before, under the command of Francisco de Eliza.

For three weeks, they cooperatively explored the Georgia Strait and the Discovery Islands area before sailing separately towards Nootka Sound (named after the Nootka tribe).

After the summer surveying season ended, in August 1792, George Vancouver went to Nootka, then the region's most important harbor, on contemporary Vancouver Island.

Here, he was to receive any British buildings and lands returned by the Spanish from claims by Francisco de Eliza for the Spanish crown.

The Spanish commander, Juan Francisco Bodega y Quadra, was very cordial, and he and Vancouver exchanged the maps they had made, but no agreement was reached; they decided to await further instructions.

At this time, they decided to name the large island on which Nootka was now proven to be located, Quadra and Vancouver Island. Years later, as Spanish influence declined, the name was shortened to simply Vancouver Island.

While at Nootka Sound, Vancouver acquired Robert Gray's chart of the lower Columbia River. Gray had entered the river during the summer before sailing to Nootka Sound for repairs.

Vancouver realized the importance of verifying Gray's information and conducting a more thorough survey.

In October 1792, he sent Lieutenant William Robert Broughton with several boats up the Columbia River. Broughton got as far as the Columbia River Gorge, sighting and naming Mount Hood.

Vancouver sailed south along the coast of Spanish Alta California, visiting Chumash villages at Point Conception and near Mission San Buenaventura.

In November, he entered San Francisco Bay, later visiting Monterey; in both places, he was warmly received by the Spanish. Vancouver spent the winter in continuing exploration of the Sandwich Islands.

After spending the winter, he made a visit to Cook Inlet. After sufficiently exploring the inlet, he returned home to England, where he sailed around Cape Horn and back to his native homeland. Thus completing a circumnavigation of the globe.

Death

Vancouver faced difficulties when he returned home to England. The accomplished and politically well-connected naturalist Archibald Menzies complained that his servant had been pressed into service during a shipboard emergency; sailing master Joseph Whidbey had a competing claim for pay as expedition astronomer; and Thomas Pitt, 2nd Baron Camelford, whom Vancouver had disciplined for numerous infractions and eventually sent home in disgrace, proceeded to harass him publicly and privately.

Pitt's allies, including his cousin, Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger, attacked Vancouver in the press. Thomas Pitt took a more direct approach; on 29 August 1796, he sent Vancouver a letter heaping many insults on the head of his former captain and challenging him to a duel.

Vancouver gravely replied that he was unable "in a private capacity to answer for his public conduct in his official duty" and offered instead to submit to a formal examination by flag officers.

Pitt chose instead to stalk Vancouver, ultimately assaulting him on a London street corner. The terms of their subsequent legal dispute required both parties to keep the peace, but nothing stopped Vancouver's civilian brother Charles from interposing and giving Pitt blow after blow until onlookers restrained the attacker.

Charges and counter-charges flew in the press, with the wealthy Camelford faction having the greater firepower until Vancouver, ailing from his long naval service, died.

George Vancouver, a man of the sea and great discoveries, was once one of the most well-known men in England who died in obscurity. He was only 40 years old.