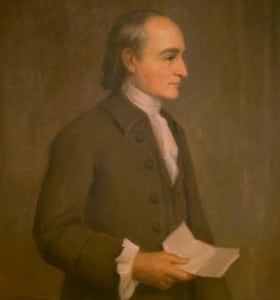

George Wythe (1726 – June 8, 1806) was a signer of the Declaration of Independence who served as a delegate of the Commonwealth of Virginia. While his name tends to be left off of the pages of the history books, he was one of the more influential founders of the Second Continental Congress.

His influence was not with speech or pen but with whom he had mentored. He, like fellow signer John Witherspoon, mentored many of the signers and future leaders of America. Under his mentorship came James Monroe, John Marshall, and St. George Tucker, but none were as close to him as one of his best students, Thomas Jefferson.

Wythe's name appears on the Declaration of Independence, but that is not the story that defines his life. In fact, his life is not the most notable aspect of his biography. It is his death that raises many questions.

Jump to:

Around the age of eighty years old George Wythe was murdered by his grand-nephew, who bore his name, George Wythe Sweeney.

The details of his murder are a bit sketchy due to the unfortunate law in Virginia that did not allow blacks to testify against whites. This allowed Sweeney to be acquitted, as there were no practical witnesses.

Life and Career of George Wythe

George Wythe was born in 1726 in the largest of the 13 original colonies, Virginia. He received much of his early education from his mother, who homeschooled him. Unfortunately, the lives of Mr. and Mrs. Wythe were cut short and left young George alone.

This caused great distress to George, who was still in his formative years and without a father or a mother to guide him. His literary studies were neglected, and he sought after a life of entertainment and not discipline. '

His poor choices would continue to hamper his life until the age of thirty, when the principles that his parents had taught him finally began to sprout from their roots. He had never lost the knowledge they taught him but chose to ignore it.

At the age of thirty, there was an undeniable turnaround in the life of Wythe. He dedicated himself to his studies and pursued an education in the law.

Here, he would study under Dr. John Lewis and shed the follies of his youth for the wisdom of his parents and mentors. He became a diligent student who displayed an exemplary work ethic and had much integrity.

During this time period, many of the great legal minds lived in Virginia. Wythe would rise through these ranks and gain influence due to his natural eloquence, persuasiveness, astute legal mind, and industry.

He would soon be one of the most respected legal minds in the Commonwealth and be in a position to influence the future generations of Virginia and the United States of America. He had grown from a young man who lived a foolish lifestyle to a man of the law. It is one of the great American stories.

George Wythe's legal practice would become the most influential practice in Virginia. Students such as Thomas Jefferson, Henry Clay, James Madison, John Breckinridge, John Marshall, and St. George Tucker would aid Wythe in his practice. During this time, Thomas Jefferson and George Wythe would become close. Throughout their friendship, the two would read and discuss philosophy, classical literature, and other great literary works.

A career in law tends to lead to a life in public service, and that is what it did for George Wythe. In 1768, Wythe was elected mayor of Williamsburg, Virginia, and in 1775, he was elected to serve as a delegate to the Continental Congress. During the Second Continental Congress, he voted in favor of declaring independence from Great Britain and would go on to serve as the Speaker of the Virginia House of Delegates in 1777.

In 1779, he was appointed as the Chair of Law at William and Mary University and became the first law professor of the newly formed United States of America.

In 1787, with the new nation at odds with each other, he served alongside Alexander Hamilton and Charles Pinckney at the Constitutional Convention. The three men were appointed by George Washington to draw up the rules and procedures for the Convention.

In 1789, at the age of 65, he was appointed Judge of the Chancery Court of Virginia.

Marriage and family

George Wythe married Anne Lewis in 1748, but the marriage was short-lived. She died 8 months later, and he then remarried six years later to Elizabeth Taliaferro.

George and Elizabeth had one child that died in infancy. Elizabeth would be George's wife throughout his rise in Virginia and the American Revolutionary War. She died the same year that the Constitutional Convention was held. After her death, Wythe moved from Williamsburg to Richmond.

Although Virginia was synonymous with slavery and the slave trade, Wythe would become one of the exceptions. He owned slaves while he was married, but after the death of Elizabeth, he freed a female slave, Lydia Broadnax, and a male slave, Benjamin.

After the Revolutionary War, Wythe would become a staunch abolitionist and speak against slavery for the rest of his life. This led to some accusations that Lydia was his concubine and that Michael Brown was his son. This may or may not have been true, but most dismiss it. However, there is no doubt that George, Lydia, and Michael shared a close bond as she moved with him to Richmond.

Wythe also opened his home up to his troubled grandnephew, who shared his name: George Wythe Sweeney. In a short time, Wythe learned that Sweeney had certain vices that he could not control. Sweeney had inclinations towards alcoholism and gambling, each of which he could not control. These sins consumed him and eventually led him to do the unthinkable.

The Murder of George Wythe

George Wythe resided at his home in Richmond for the final years of his life. During this time, he was joined by his faithful servant, Lydia Broadnax, and a couple of young students. One of his students bared his name, George Wythe Sweeney, and was his great-grandnephew, and the other was Mike Brown, who was a mulatto that Wythe had taken under his wing.

Sweeney was a troublemaker and probably reminded his great-uncle of himself in his younger years. However much he reminded him, Wythe was not ignorant to Sweeney's actions.

Sweeney continuously stole from his great-uncle and had been caught forging his signature on bad checks six times. He had lived with his uncle sporadically and had acquired a sense of entitlement. His behavior towards his uncle never changed. Sweeney had a problem with his vices. He was an alcoholic and a compulsive gambler, and he had no qualms about stealing from his great-uncle to support his addictions.

Shortly before Wythe's untimely death, he had spoken to his grand-nephew and told him that if he did not change his ways, he would cut him out of his will completely. Wythe's will was extraordinary, and Sweeney was set up to acquire a bit of money from his great-uncle. His behavior only worsened.

Brown, on the other hand, was a mulatto who was born of a slave and had been taken under the wing of Wythe. He showed tremendous character and intelligence and quickly impressed his teacher.

The old signer and founding father continued to teach him and had so much affection for him that he was given a spot in his will and would be bequeathed a large sum of money. This is something that Sweeney resented and would ultimately cost Wythe his life.

Shortly before Wythe's death, Lydia spotted Sweeney reading the will of his great-uncle. He was acting noticeably different and a bit uneasy.

He requested that Lydia make him some toast, and during that time, it is believed that he slipped some powder into the coffee pot. Lydia then made breakfast for her, Brown, and Wythe and served it to each of them. One by one, each of the three doubled over and had intense stomach cramps with vomiting.

Three doctors were sent, and each of them assessed the sick. It was during this time that George Wythe sat up and told the doctors, "I am murdered." Brown would be the first to die.

At first, the doctors believed it to be an outbreak of cholera, but Wythe knew better and told the doctors that this was Sweeney's doing. Wythe, feeling death at his door, sent for his lawyer and wrote his great-nephew completely out of the will. Whatever may happen to Sweeney in his life would happen to him without his inheritance.

Lydia recovered from the arsenic, but George Wythe would breathe his last on June 8, 1806. His funeral would be the largest that Virginia had seen. He left a grand legacy.

The Trial of George Wythe Sweeney

Sweeney was arrested for forgery and then put on trial for the murder of his uncle. The evidence against him was overwhelming, and it looked as if it would be an open-and-shut conviction. However, there was a law in Virginia that would prove to be difficult for the prosecutor to argue past.

A law that Wythe and his protegé Jefferson had not been able to rid of when they wrote the Virginia Constitution. A law that stated that a black could not testify against a white, regardless of their freedom. Lydia's testimony would never be heard, and the evidence that had been mounted against Sweeney could not be used.

Sweeney was released. Justice was not served due to the racism of Virginia.

History finds Sweeney in Tennessee some years later. He was thrown into jail for horse theft and served several years. After his release, he vanishes from the pages of history.

If you would like to read more details of the Murder of George Wythe, then I would recommend this article written by Bruce Chadwick.