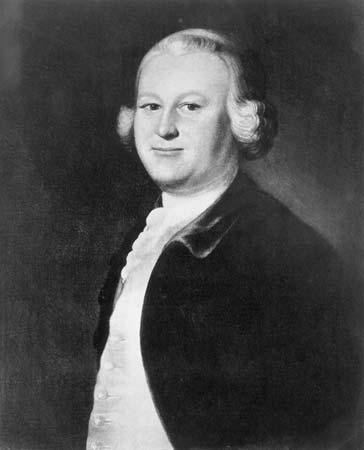

James Otis Jr. (February 5, 1725 – May 23, 1783) was a lawyer in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, a member of the Massachusetts provincial assembly, and an early advocate of the Patriot views against British policy that led to the American Revolution. His catchphrase, "Taxation without representation is tyranny," became the basic Patriot position.

The following is a list of 21 important James Otis facts.

Jump to:

James Otis Facts: Early Life

- James Otis was born in West Barnstable, Massachusetts. He was the second of thirteen children and the first to survive infancy.

- His sister Mercy Otis Warren, his brother Joseph Otis, and his youngest brother Samuel Allyne Otis became leaders of the Revolution, as did his nephew Harrison Gray Otis. His father, Colonel James Otis Sr., was a prominent lawyer and militia officer.

- In 1755, James married "the beautiful Ruth Cunningham," a merchant's daughter and heiress to a fortune worth 10,000 pounds. Their politics were quite different, yet they were attached to each other.

- The marriage produced three children (James, Elizabeth, and Mary). Their son James died at the age of eighteen, and their daughter Elizabeth, a Loyalist like her mother, married Captain Brown of the British Army and lived in England for the rest of her life.

- Their youngest daughter, Mary, married Benjamin Lincoln, son of the distinguished Continental Army General Benjamin Lincoln.

James Otis Facts: Writs of Assistance

- James Otis graduated from Harvard in 1743 and rose quickly to the top of the Boston legal profession.

- In 1760, he received a prestigious appointment as Advocate General of the Admiralty Court. He promptly resigned, however, when Governor Francis Bernard failed to appoint his father to the promised position of Chief Justice of the province's highest court; the position instead went to longtime Otis opponent Thomas Hutchinson.

- In a dramatic turnabout following his resignation, Otis instead represented pro bono the colonial merchants who were challenging the legality of the "writs of assistance" before the Superior Court, the predecessor of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court.

- These writs enabled British authorities to enter any colonist's home with no advance notice, no probable cause, and no reason given. In his oration against the writs, John Adams recollected years later, "Otis was a flame of fire; with a promptitude of classical allusions, a depth of research, a rapid summary of historical events and dates, a profusion of legal authorities."

- James Otis considered himself a loyal British subject. Yet in February 1761, he argued against the Writs of Assistance in a nearly five-hour oration before a select audience in the State House. His argument failed to win his case, although it galvanized the revolutionary movement.

- John Adams promoted Otis as a major player in the coming of the American Revolution. Adams said, "I have been young, and now I am old, and I solemnly say I have never known a man whose love of country was more ardent or sincere, never one who suffered so much, never one whose service for any 10 years of his life were so important and essential to the cause of his country as those of Mr. Otis from 1760 to 1770." Adams claimed that "the child independence was then and there born, every man of an immense crowded audience appeared to me to go away as I did, ready to take arms against writs of assistance."

- James Otis's challenge to the authority of Parliament made a strong impression on John Adams and many other revolutionaries in Boston.

- James Otis did not identify himself as a revolutionary; his peers, too, generally viewed him as more cautious than the fiery Samuel Adams.

James Otis Facts: The Patriot

- Originally politically based in the rural Popular Party, Otis effectively made alliances with Boston merchants so that he instantly became a patriot star after the controversy over the writs of assistance.

- He was elected by an overwhelming margin to the provincial assembly a month later. Otis subsequently wrote several important patriotic pamphlets, served in the assembly, and was a leader of the Stamp Act Congress.

- He also was friends with Thomas Paine, the author of Common Sense.

- Otis suffered from increasingly erratic behavior as the 1760s progressed. Otis received a gash on the head by British tax collector John Robinson's cudgel at the British Coffee House in 1769. Some mistakenly attribute Otis's mental illness to this event alone, but John Adams, Thomas Hutchinson, and many others mention Otis's mental illness well before 1769.

- While it was not the cause, the blow to the head Otis received made the mental illness he suffered far worse, and shortly after, he could no longer continue his work.

- By the end of the decade, Otis's public life largely came to an end. Otis was able to do occasional legal practice during times of clarity.

- Unique in his era, Otis favored extending the basic natural law freedoms of life, liberty, and property to African Americans. He asserted that blacks had inalienable rights. The idea of racial equality also permeates Otis's Rights of the British Colonies (1764), in which he stated: The colonists are by the law of nature free born, as indeed all men are, white or black.

- Otis died suddenly in May 1783 at the age of 58 when, as he stood in the doorway of a friend's house, he was struck by lightning. He is reported to have said to his sister, Mercy Otis Warren, "My dear sister, I hope when God Almighty in his righteous providence shall take me out of time into eternity that it will be by a flash of lightning."