Maryland Colony was a British colony that existed from 1632 until 1776, when it joined the other twelve of the 13 original colonies in rebellion against Great Britain and became the U.S. state of Maryland.

Its first settlement and capital was St. Mary's City, in the southern end of St. Mary's County, which is a peninsula in the Chesapeake Bay and is also bordered by four tidal rivers.

Maryland Colony began as a proprietary colony of the English Lord Baltimore, who wished to create a haven for English Catholics in the new world at the time of the European wars of religion.

Jump to:

- Maryland Colony Facts: The Founding

- Maryland Colony Facts: Early Settlers

- Maryland Colony Facts: Native American Relations

- Maryland Colony Facts: Religious Conflict

- Maryland Colony Facts: Colonial Economy

- Maryland Colony Facts: Pre-Revolution

- Maryland Colony Facts: American Revolutionary War

- Maryland Colony Facts: Online Resources

Although Maryland was an early pioneer of religious toleration in the English colonies, religious dissent among Anglicans, Puritans, Catholics, and Quakers was common in the early years, and Puritan rebels briefly seized control of the colony.

In 1689, the year following the Glorious Revolution, John Coode led a rebellion that removed Lord Baltimore from power in Maryland. Power in the colony was restored to the Baltimore family in 1715 when Charles Calvert, 5th Baron Baltimore, insisted in public that he was a Protestant.

Despite early competition with the Virginia Colony to its south and the Dutch colony of New Netherland to its north, the Province of Maryland developed along very similar lines to Virginia.

Its early settlements and population centers tended to cluster around the rivers and other waterways that empty into the Chesapeake Bay, and, like Virginia, Maryland's economy quickly became centered on the cultivation of tobacco for sale in Europe.

The need for cheap labor, and later with the mixed farming economy that developed when tobacco prices collapsed, led to a rapid expansion of indentured servitude, penal transportation, and forcible immigration and slavery.

Maryland Colony was an active participant in the events leading up to the American Revolutionary War and echoed events in the New England Colonies by establishing committees of correspondence and hosting its own tea party similar to the one that took place in Boston.

By 1776, British rule had been removed, and the citizens and their leaders wanted independence from Great Britain.

Maryland Colony Facts: The Founding

The 1st Baron Baltimore, Catholic George Calvert, wanted to build a safe place for Catholics in the New World. After having visited the Americas and earlier founding a colony in the future Canadian province of Newfoundland called "Avalon," he convinced King Charles I to grant him a second territory in more southern temperate climes. Upon Calvert's death in 1632, the grant was transferred to his oldest son Cecil.

On June 20, 1632, Charles I of England granted the original charter for Maryland, a proprietary colony of about twelve million acres, to Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore.

The charter offered much freedom, including no requirement for religion. The charter had originally been granted to Calvert's father, George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore, but the 1st Baron Baltimore died before it could be executed, so it was granted to his son instead.

Whatever the reason for granting the colony specifically to Baltimore, however, the King had practical reasons to create a colony north of the Potomac in 1632. The colony of New Netherland, founded by the Dutch, was a rival of England and posed a threat to them in the New World. King Charles I set up the Maryland colony to rival the colony of New Netherlands that was to the north of them.

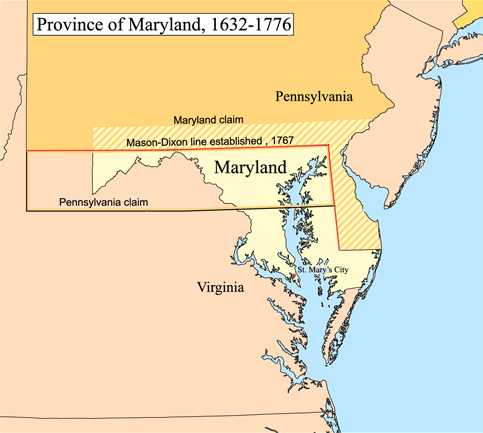

Colonial Maryland was considerably larger than the present-day state of Maryland. The original charter granted the Calverts an imprecisely defined territory north of Virginia and south of the 40th parallel, comprising perhaps as much as 12 million acres.

Maryland Colony Facts: Early Settlers

In Maryland, Baltimore sought to create a haven for English Catholics and to demonstrate that Catholics and Protestants could live together peacefully, even issuing the Act Concerning Religion in matters of religion.

Cecil Calvert was himself a convert to Catholicism, a considerable political setback for a nobleman in 17th-century England, where Roman Catholics could easily be considered enemies of the crown and potential traitors to their country. Like other aristocratic proprietors, he also hoped to turn a profit on the new colony.

The Calvert family recruited Catholic aristocrats and Protestant settlers for Maryland, luring them with generous land grants and a policy of religious toleration. To try to gain settlers, Maryland used what is known as the headright system, which originated in Jamestown. Settlers were given 50 acres of land for each person they brought into the colony, whether as a settler, indentured servant, or slave.

Of the 200 or so initial settlers who traveled to Maryland on the ships Ark and Dove, the majority were Protestant.

On November 22, 1633, Lord Baltimore sent the first settlers to the new colony, and after a long voyage with a stopover to resupply in Barbados, the Ark and the Dove landed on March 25, 1634, at Blackistone Island, thereafter known as St. Clement's Island, off the northern shore of the Potomac River, upstream from its confluence with the Chesapeake Bay and Point Lookout.

The new settlers were led by Lord Baltimore's younger brother, Leonard Calvert, whom Baltimore had delegated to serve as governor of the new colony.

They made their first permanent settlement in what is now St. Mary's County, choosing to settle on a bluff overlooking the St. Mary's River, a relatively calm, tidal tributary to the mouth of the Potomac River where it empties into the Chesapeake Bay.

The site was already a Native American village when they arrived, but the settlers had with them a former Virginia colonist who was fluent in their language, and they met quickly with the paramount chief of the region.

He knew of white men from communication with native tribes to the South and West in Virginia, and he was eager to gain technology, such as guns and gunpowder, from the Maryland settlers. He met the settlers shortly after their arrival and soon reached a treaty with them, almost immediately agreed to sell them the land.

The new settlement was called "St. Mary's City," and it became the first capital of Maryland and remained so for sixty years until 1695 when the colony's capital was moved north to the more central, newly established "Anne Arundel's Town" and later renamed as "Annapolis."

More settlers soon followed, and St. Mary's City. The tobacco crops that they had planned from the outset were very successful and made the new colony profitable very quickly. However, given the incidence of malaria and typhoid, life expectancy in Maryland was about 10 years less than in New England.

Maryland Colony Facts: Native American Relations

In 1642, the Province of Maryland declared war on the Susquehannock Indian nation. The Susquehannock defeated Maryland in 1644.

As a result, the Conestoga traded almost exclusively with New Sweden to the north while the colony was young. The Susquehannocks remained in an intermittent state of war with Maryland until a peace treaty was concluded in 1652, but would become allies in the following decades.

In the peace treaty of 1652, the Susquehannock ceded to Maryland large territories on both shores of the Chesapeake Bay in return for arms and safety on their southern flank. During this time, the Maryland natives had hostile relations with the Iroquois Confederacy. The Iroquois had been expanding to acquire more hunting grounds to increase their fur trade.

The treaty worked well for both involved. It provided the Susquehannock with better technology and protection on their flank, while it provided the colonists with a buffer between them and the powerful Iroquois. Eventually, the power of the Iroquois and disease overwhelmed the Susquehannock, and over time they faded.

Maryland Colony Facts: Religious Conflict

The Maryland Colony was begun with the idea that Catholics and Protestants could co-exist with each other. While they had success in that endeavor, there was still conflict.

Dissension among Anglicans, Puritans, Roman Catholics, and Quakers was common, and at one point, the Puritans seized control of the colony. By 1649, Maryland passed the Maryland Toleration Act, which mandated religious tolerance. This was the first law passed that required religious tolerance in the New World.

Over time, Protestants outnumbered Catholics in the region, and the Great Awakening increased that number. By the time of the American Revolutionary War, Maryland was almost exclusively Protestant. However, they did supply the only Catholic delegate to the Continental Congress, Charles Carroll of Carrollton.

Maryland Colony Facts: Colonial Economy

Early settlements and population centers tended to cluster around the rivers and other waterways that empty into the Chesapeake Bay. In the 17th century, most Marylanders lived in rough conditions on small farms. While they raised a variety of fruits, vegetables, grains, and livestock, the main cash crop was tobacco, which soon dominated the province's economy.

Maryland Colony developed along lines very similar to those of the colony of Virginia. Tobacco was used as money, and the colonial legislature passed a law requiring tobacco planters to raise a certain amount of corn as well in order to ensure that the colonists would not go hungry.

Like Virginia, Maryland's economy quickly became centered around the farming of tobacco for sale in Europe.

The need for cheap labor to help with the growth of tobacco, and later with the mixed farming economy that developed when tobacco prices collapsed, led to a rapid expansion of indentured servants and eventually slavery.

Outside the plantations, much land was operated by independent farmers who rented from the proprietors or owned it outright. They emphasized subsistence farming to grow food for their large families. Many of the Irish and Scottish immigrants specialized in rye-whiskey making, which they sold to obtain cash.

These frontiersmen would play important roles during the American Revolutionary War.

Maryland Colony Facts: Pre-Revolution

Maryland developed into a plantation colony by the 18th century. In 1700, there were about 25,000 people, and by 1750, that had grown more than 5 times to 130,000. By 1755, about 40% of Maryland's population was black. Maryland planters also made extensive use of indentured servants and penal labor.

An extensive system of rivers facilitated the movement of produce from inland plantations and farms to the Atlantic coast for export. The port of Baltimore became the 2nd most important port in the southern colonies, only surpassed by the Port of Charleston located in the South Carolina Colony.

In the later colonial period, the southern and eastern portions of the colony continued in their tobacco economy, heavily dependent on slave labor, but as the revolution approached, northern and central Maryland increasingly became centers of wheat production.

This helped drive the expansion of interior farming towns like Frederick and Maryland's major port city of Baltimore.

Maryland Colony Facts: American Revolutionary War

Up to the time of the American Revolutionary War, the Maryland Colony was one of two colonies that remained an English proprietary colony, Pennsylvania being the other.

Maryland declared independence from Britain in 1776, with Samuel Chase, William Paca, Thomas Stone, and Charles Carroll of Carrollton signing the Declaration of Independence for the colony. In the 1776–77 debates over the Articles of Confederation, Maryland delegates led the party that insisted that states with western land claims cede them to the Confederation government, and in 1781, Maryland became the last state to ratify the Articles of Confederation.

It accepted the United States Constitution more readily, ratifying it on April 28, 1788.

Maryland also gave up some territory to create the new District of Columbia after the American Revolution.

While there were no major battles fought in Maryland during the American Revolutionary War, the citizens of the colony distinguished themselves in their service. There were excellent gunsmiths in the area that supplied the Continental Army with weapons, and the men that fought earned an excellent reputation.

They were an important piece in George Washington's Continental Army and earned high praise from the Commander-in-chief.

Maryland Colony Facts: Online Resources

- Wikipedia - Province of Maryland

- The Maryland Gazette

- Maryland Historical Society

- Frederick Douglass Family Tree

- The History Junkie's Guide to Colonial America

- The History Junkie's Guide to Southern Colonies

- The History Junkie's Guide to the Signers of the Declaration of Independence

- The History Junkie's Guide to American Revolutionary War Facts