The glorious assault on the Union center on July 3, 1863, is often referred to as Pickett's Charge. The assault was led by Confederate Major General George Pickett and his fresh division, as they had arrived at Gettysburg the night before and had not seen battle.

The Plan

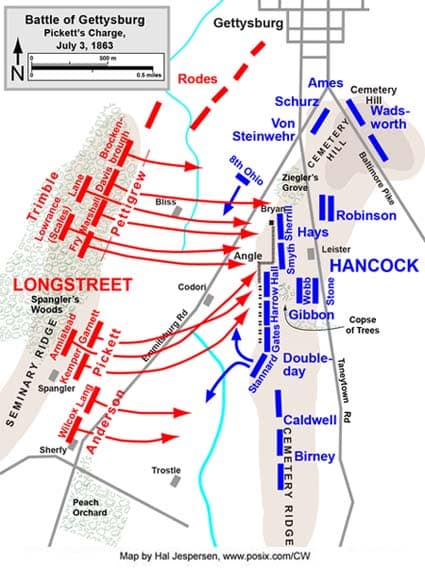

General Robert E. Lee's plan of attack that morning was to assault the Union center with 12,000 troops, with General James Longstreet coordinating the attack. After a devastating artillery attack that would loosen up the Union defenses, the Confederates would attack and break the Union center and split the army in two.

The 5,000 men in Pickett's division would be the only ones from Longstreet's corps. His two other divisions under Hood and McLaws had suffered too many casualties the day before to participate. Heth's division had a full day of rest after fighting on July 1, 1863, but since he had a head wound, they would be lead by Brigadier General James Johnston Pettigrew. Other Confederate divisions would bolster the attacking force, and close to 12,000 men would line up in the woods along Seminary Ridge for the assault across an expanse of close to a mile of open ground.

On the other side of the battlefield stood Union General Winfield S. Hancock and the II Corps. The "copse of trees" in the center of Hancock's lines was the focus of the Confederate assault. General George Meade had correctly suggested that Lee would attack the Union center at this position, and his headquarters stood just behind the Union lines at the home of widow Lydia Leister.

Dissention and Artillery Assault

General James Longstreet was not in agreement with Lee that this assault would be effective. He had been in this scenario before in Marye's Heights over Fredericksburg, in which his men had the stone wall, and the Union lines were decimated each time they attacked. The distance the Confederates had to cover was another concern, and they would be fully exposed to artillery fire and muskets the entire charge. Longstreet had met with Lee that morning and implored him to move the army to the east and south rather than attack and put themselves between the Union army and Washington. He believed this would force Meade into attacking, yet Lee was determined to strike the enemy where they stood.

Preceding the infantry charge, Lee planned an artillery barrage that would be unlike any other in the war to that point. Colonel Edward Porter Alexander was the chief artillery corps commander and was just 27 years old. With roughly 150 guns, the Confederates began the action at 1 p.m., and their goal was to knock off as many Union guns as possible and strike fear into the enemy with the impressive barrage. The Union artillery responded with 80 guns and lasting nearly 2 hours. Most of the cannon shots from both sides landed beyond the targets and had little effect but to delay the battle. Meade was, in fact, forced to retreat from his headquarters to the east due to heavy artillery fire in his vicinity. The Union artillery commander, Brigadier General Henry J. Hunt, hoped to deceive the Confederates by slowing his fire, then slowly ceasing to create the illusion that he was running out of ammunition.

Colonel Alexander did believe that his artillery barrage had knocked out Union artillery emplacements, and with this and because he was running low on ammunition, he recommended that the Confederate infantry attack begin. After Alexander had notified Pickett, Longstreet reluctantly and with a nod gave Pickett the order to begin the assault that would later be known as Pickett's Charge.

Pickett's Charge

Pettigrew and Trimble moved forward out of the woods on the left, with Pickett's division advancing forward on the right. They were to march in formation across the 1,000-yard expanse of the field, then charge when they reached within a few hundred yards of the enemy. The Confederate ranks were close to a mile wide and, through a series of obliques, would concentrate their forces in the middle by the copse of trees marking the Union lines.

The Confederates were under constant long-range artillery fire, and this created ghastly holes in their ranks. As the Confederates advanced, they began receiving artillery fire on their ranks from Union positions on Little Round Top and Cemetery Hill. The Union artillery started with solid and shells, and as the Confederates drew closer, they switched to canister. When the Confederates were 400 yards away, the Union lines piled musket fire into ranks from behind the protection of the stone wall during Pickett's Charge.

The Confederate ranks were steadily decimated, and their lines were now close to ½ mile long as Pettigrew moved to the right and Pickett toward the left, converging toward the Union lines.

The Confederate left started to break up from constant artillery fire and a surprise attack from the 8th Infantry Ohio regiment. 160 men suddenly sprang up from the grass from hidden positions and fired into the left flank of Brockenbrough's brigade. His men retreated in a panic to the rear through Trimble's division, putting them into disarray as well.

Pickett's division was made up of 2 brigades in the lead, Brigadier Generals James L. Kemper on the right and Richard B. Garnett on the left. They were followed by an additional brigade under Brigadier General Lewis A. Armistead. As they wheeled left while crossing Emmitsburg Road, Kemper's brigade was exposed to devastating fire during Picketts Charge. Union Brigadier General George J. Stannard's brigade made up of the 13th, 14th, and 16th Vermont regiments, was able to flank Kemper and punish them with continuous musket fire.

On the Union side, General Hancock was wounded in the thigh, and he issued and order that he not be removed from the battlefield until the engagement was decided.

As they advanced, the Confederates massed in the center, roughly 15-30 men deep, and concentrated the attack toward "The Angle," a 90-degree angle created by a stone wall. Defending the angle was the 71st Pennsylvania, comprised of 250 men. Adjacent and to their left was the 69th Pennsylvania and the 1st New York Independent artillery. They kept up a continuous fire, but the Confederates still came. Finally, the Confederates reached the stone wall with roughly 200 men led by General Armistead, who had put his hat on his sword. They stormed the wall and fought hand-to-hand with the Union soldiers.

Inexplicably, the 71st Pennsylvania was ordered to retreat, and this left the 69th alone to fight the Confederates. Then 72nd Pennsylvania (Zouves) regiment was ordered forward. At this time, General Armistead was mortally wounded, and as Union reinforcements arrived, Pickett's Charge stalled. Without leaders, the remainder of the Confederates either retreated, were killed, or were captured.

Outcome

The Confederates had over 50% casualties, while the Union had only 1,500 casualties total. General Lee rode up to meet his troops as they retreated and exclaimed that the failure "was all my fault." When Lee, fearing a counterattack, asked Pickett to reform his division, Pickett remarked: "General Lee, I have no division". Pickett would never forgive Lee for ordering the charge for the remainder of his life. The Confederates were forced to evacuate to Virginia and would never penetrate the North again for the remainder of the war, which lasted another 2 years. Pickett's Charge will forever be regarded as one of the bravest assaults in military history.