The Raid on Harper's Ferry was an attempt by John Brown and his followers to begin a slave revolt at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Brown's party of 22 was defeated by the U.S. Marines, which was led by Robert E. Lee.

Jump to:

Raid on Harper's Ferry Prelude

John Brown rented the Kennedy Farmhouse 4 miles north of Harper's Ferry. He changed his name to Isaac Smith.

He showed up at Harper's Ferry with a small group of men (13 white men and 5 black men)

He was supported by Northern abolitionist groups that sent weapons and ammunition.

Brown attempted to recruit more men, specifically black recruits. He failed to recruit Frederick Douglass but successfully recruited Shield Green.

Everyone stayed at the Kennedy Farmhouse, which served as a barracks, mess hall, supply depot, and anything else that Brown and his men needed.

Brown worried about the neighbors becoming suspicious of so many men being housed in one location, so the men only came out in the evening. During the day, they drilled, argued politics, and passed the time with different activities.

John Brown's strategy was to take Harper's Ferry and arm the slaves located there. He believed that he would get much support from slaves and abolitionists. He would then take the Appalachian Mountains south into Tennessee and Alabama into the heart of the South, causing fear and destruction wherever he went.

The Raid on Harper's Ferry Begins

On October 16, 1859, Brown left the Kennedy Farmhouse and went to the town of Harper's Ferry, Virginia.

He sent John Cook Jr to capture Lewis Washington, great-grandnephew of George Washington, some of his slaves, and two relics of George Washington.

Brown and his men continued towards Harper's Ferry and captured several watchmen and townspeople along the way.

They cut the telegraph wire and seized a Baltimore & Ohio train passing through.

They shot and killed a free black man, Hayward Shepherd, who confronted the raiders on the train.

The conductor of the train alerted the authorities down the line, but Brown's resolve did not waver. He believed that he would win the support of local slaves.

Word had not been spread about the uprising. Therefore, slaves did not know that it was even happening. The uprising never occurred.

White townspeople began fighting back, but the raiders continued and successfully captured the armory in Harper's Ferry that evening.

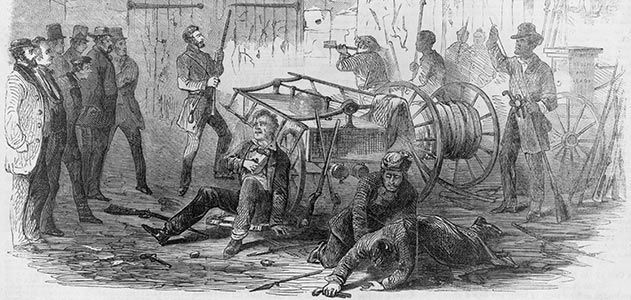

The next day, Brown's raid began to fall apart. The local militia cut off his only escape route, and many of his men began to get shot and killed. The local militia cornered Brown and his men in a small engine room. At this point, Brown had already lost two of his sons in the raid.

President James Buchanan ordered a company of U.S. Marines to march on Harper's Ferry. The company was led by Robert E. Lee.

On the morning of October 18, Lee sent a J. E. B. Stuart under a flag of truce to negotiate with the raiders. The raiders declined, and the marines began their actions. They used a ladder as a battering ram to open the door and quickly eliminated the raiders, including the capture of John Brown.

Robert E. Lee wrote a synopsis of the action and stated that he believed John Brown to be a madman.

Raid of Harper's Ferry Aftermath

John Brown and his remaining men went to trial and were found guilty of treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia.

Brown was hanged for his actions on December 2, 1859. He believed that if his actions would have been directed to help the wealthy class rather than the class of slaves, that perception would have been different.

While many believed that John Brown was a madman and his plans were misguided, his trial was almost prophetic. In his last words, he stated that he believed the sins of this nation would not be corrected without a lot of bloodshed. His words would become true.

The initial Southern reaction was fear that their slaves would revolt.

The Northern reaction was sympathetic, and Brown would eventually become known as a martyr.