The Second Battle of Bull Run was fought August 28-30, 1862, near Manassas, Virginia. It involved the Army of Northern Virginia under General Robert E. Lee and the Union's Army of Virginia led by General John Pope. This victory would continue to enhance the reputation of Robert E. Lee at the beginning of the Civil War.

Prelude

In June 1862, President Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton were searching for a solution to an embarrassing deadlock in Virginia. Federal operations in the trans-Allegheny west had gone relatively well with the capture of Forts Henry and Donelson and the standoff at the Battle of Shiloh.

By comparison, in the east, Northern units had experienced a chain of defeats at the hands of Stonewall Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley. The superbly equipped and trained Army of the Potomac, from which so much had been expected, was in an apparent stalemate before attempting to seize Richmond after inching its way for months up the Peninsula. The two civilian leaders brought two Western generals to Virginia in the hope of reviving the situation.

The first to arrive was Maj. Gen. John Pope, was appointed on 26 June 1862 to command a new creation, the Army of Virginia. This force was composed of the various hitherto independent commands that had operated to such little effect in Northern Virginia and the Shenandoah Valley that spring. Many of the units collectively had experienced a severe hammering from Stonewall Jackson, while others were suffering from a lack of discipline and poor leadership.

General Pope was followed on 11 July by Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, who was appointed General in Chief with directing authority over both Pope and Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, commanding the Army of the Potomac on the Peninsula.

The 26 June orders creating the Army of Virginia specified that it should "operate in such manner as while protecting Western Virginia and the national capital from danger or insult, it shall in the speediest manner attack and overcome the rebel force under Jackson and Ewell, threaten the enemy in the direction of Charlottesville and render the most effective aid to relieve Gen. McClellan and capture Richmond."

General Pope knew by the time he received his orders that Jackson had left the Valley and was with Lee near Richmond. Thus, he saw his mission as covering Washington from any attacks from the direction of Richmond while deploying to assure the safety of the Valley.

He felt further that he should position himself to pull Southern troops away from Richmond, thus indirectly aiding McClellan. Pope believed these objectives could be met best by concentrating his scattered forces in the Sperryville-Warrenton area. Doing so allowed him to safeguard the approaches to the Valley. At the same time, his position threatened the important railroad and depot center at Gordonsville, virtually forcing Lee to send troops from Richmond to protect it.

Bringing his forces together allowed Pope to assess the polyglot units he had inherited and to begin establishing teamwork and standards. The Army of Virginia needed all the training it could get. There were tensions among the senior officers, particularly those from the Army of the Potomac who saw Pope as a threat to their idol General McClellan. Staff inexperience was revealed throughout the summer campaign by poor march planning, improper terrain appreciation, and disregard for logistical aspects.

The supply problem was compounded by poor load planning on the part of the Army of the Potomac units deploying as reinforcements from the Peninsula. Many arrived without basic ammunition loads or critical equipment items. The effect of this lack of experience was that Pope's army seemed like a balky team. Its movements were slow and were accomplished with great friction. Staff work was poor and undeveloped, and the new commander did little to help.

General Pope was a man of little tact, often discourteous and overbearing, arrogant and boastful. A pompous assumption of command address to his overworked troops compared them unfavorably to the men he had led in the West, alienating his Easterners permanently. Soon after taking command, Pope issued orders that stirred up the civil populace and embittered many Southerners against him. The orders authorized foraging, directing Union troops to subsist off the country. The intent of the orders apparently was to restrict guerrilla activity but seemed more to encourage violence against civilians. His actions led General Lee to declare that the Pope had to be "suppressed."

Pope's threat to Gordonsville led Lee to send Stonewall Jackson on 13–16 July with his and Richard Ewell's Divisions to protect that place. By 27 July, Pope's growing strength caused Lee to add A. P. Hill's Division, raising Jackson's force to about 24,000 men. Lee was able to risk reducing the Richmond defenses because of McClellan's inactivity and indications that the Army of the Potomac was preparing to leave. These signs included such things as the retrograde of wounded and the diversion of reinforcements from the Hampton area to Aquia and Alexandria on the Potomac.

On 3 August, General Halleck directed General McClellan to begin his final withdrawal from the Peninsula and to return to Northern Virginia to support Pope. McClellan protested and did not begin his redeployment until 14 August. The situation created an opportunity for General Lee. The removal of the Army of the Potomac as a threat meant that there would be a short period when he could turn on Pope's force and actually outnumber it before the merger of the two Federal armies.

Under these circumstances, Pope should have assumed a defensive role from the time Halleck had decided to move McClellan, but his flexibility was impeded by Halleck's insistence that Pope remains forward along the lines of the Rapidan and Rappahannock Rivers. Pope was required at first to keep Brig. Gen. Rufus King's Division at Aquia and Fredericksburg to secure the docks there and also to use other parts of his force to keep open the Orange and Alexandria rail line from Culpeper to Washington. This extended Pope to the maximum.

Even when King was released to him on 8 August, Pope still had to hold the river line. Halleck's insistence on this reduced Pope's planning options and exposed his force unnecessarily.

Stonewall Jackson noted this and attempted a move against Pope's forward units; however, poor staff work delayed his movements, and he collided with Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks' II Corps of the Army of Virginia. The two men's units fought a fierce battle at Cedar Mountain south of Culpeper on 9 August.

Pope's aggressive rhetoric and cautious directives had made his intentions unclear to Banks, who, in doubt, chose to attack. The battle was a virtual draw, but Jackson withdrew as the rest of Pope's force advanced to support the battered Banks. Lee joined Jackson at Gordonsville on 15 August, bringing with him by rail the corps of Pope's West Point classmate James Longstreet. A skeleton Confederate force remained in Richmond to watch McClellan depart.

Lee felt the best way for him to assure the full relief of Richmond was to unite his forces and move on to Pope. "The disparity of force between the contending forces rendered the risks unavoidable." At this point, Lee's united force of about 55,000 men slightly outnumbered Pope's.

He hoped to trap Pope in the triangle formed between the convergence of the Rapidan and Rappahannock Rivers. Again, staff planning was poor, and the Southern forces were slow to take up their attack positions. While this was taking place, on 18 August, a patrol from the 1st Michigan Cavalry encountered Maj. Gen. J. E. B. Stuart's headquarters group at Verdiersville and made off with a copy of Lee's plan.

Pope made use of the information to withdraw skillfully north of the Rappahannock on the night of 18–19 August, basing himself in Warrenton. Lee unsuccessfully probed Pope's flanks along the river for the next several days.

J. E. B. Stuart led a retaliatory raid against Pope's headquarters then at Catlett's Station during the night of 22–23 August. The Confederate cavalry made off with, among other things, Pope's dispatch book. From it, Lee learned of the Army of Virginia's dispositions as well as the expected rate of reinforcement from the Army of the Potomac. Pope's letters also revealed his plan to remain on the defensive until his strength grew.

Lee decided he had to break the stalemate along the Rappahannock quickly before he was overwhelmingly outnumbered. All the major fords along the swollen river were well covered, with most of Pope's army concentrated between Sulphur Springs and Warrenton. The Federal fight was at Waterloo, six miles northwest of Warrenton. Lee saw only one chance to change the situation, "If one runs great risks, it is for the purpose of gaining great advantages."

He thus split his forces and sent Jackson's force completely around Pope's northern flank. His objective was to bring about a decisive battle in which the advantages of position would be his, forcing Pope to fight on his terms. He knew from the captured papers that Pope was being controlled from Washington, which control required him to keep links to Aquia and along the river line, thus impairing his initiative and freedom of action.

Lee was also aware of the internal command problems and lack of cohesiveness in Pope's army and wanted to take advantage of them while he had the chance. Jackson's move would compel Pope to give up the river line to safeguard his rear, thus spreading confusion and creating the opportunity for an engagement on terms favorable to the Confederates.

Jackson did not tell his senior commanders his plans but merely started his corps moving after a conference with Lee, Longstreet, and Stuart. He left behind his quartermaster and subsistence trains but brought along his cattle herd, ordnance, and ambulance trains. The men were ordered to carry three days' rations, and foraging was allowed. The route to be followed was selected by Jackson's chief engineer, Capt. J. Keith Boswell and screened by cavalry raised in the region.

The March Around Pope

At first light on 25 August, Boswell led Jackson's force out of Jeffersontown on the road to Amiss Ville. Ewell's Division was in the lead, followed by A. P. Hill's and then Taliaferro's. The column turned northeast just past Amiss Ville, crossing the Hedgeman River at Henson's Mill. Once across, elements of the 2nd Virginia Cavalry moved ahead to screen the line of march.

The main body trudged by way of Orleans and Thumb Run Church toward Salem (modern Marshall). The issue of rations to Jackson's men had been uneven. Departure was so early that some men had been unable to cook their three days' supply; others had eaten their full issue by the end of the first day.

Thereafter, green corn and apples foraged along the way were the staple ration. The head of the column closed into bivouacs about a mile south of Salem at sunset. Later that night, Col. Thomas T. Munford, with the rest of his 2nd Virginia Cavalry Regiment, rode into town and bedded down. There had been no encounters with the enemy the entire day.

Longstreet's Corps smoothly supplanted Jackson's units along the Rappahannock, sustaining the illusion of a strong Confederate presence with artillery duels and aggressive patrolling. Late in the afternoon of the twenty-fifth, Lee sent Stuart with all his cavalry eastward to rendezvous with Jackson. Doing so deprived Longstreet of any reconnaissance capability.

General Pope, on his side, continued to array his forces on the defensive along the Rappahannock River line. The dust from Jackson's column had been noted and reported by Federal cavalry and signal stations. The Federal headquarters dismissed the information as indicating a Confederate withdrawal into the Shenandoah Valley.

Major General Fitz-John Porter and Maj. Gen. Samuel Heintzelman's Corps arrived during the day as reinforcements from the Army of the Potomac. Heintzelman's men especially were underequipped because of poor load planning incidents to their move from the Peninsula.

They did not have their corps reserve stocks with them; consequently, the infantry units carried only the minimum basic ammunition load. Porter's Fifth Corps had marched up the Rappahannock from Aquia and had considerable difficulty discovering its final destination. Pope had failed to send guides or guidance to the corps commander while he was en route.

Jackson renewed his advance early on 26 August. The most likely blocking position on the next day's route was Thoroughfare Gap. Accordingly, Jackson hastened Munford's Regiment forward at dawn to hold it. The horsemen found the Gap unoccupied, and the infantry followed them through White Plains to the Gap and on to the village of Haymarket.

The dust covered Jackson's troops, and his officers continually pressed the infantrymen to stay closed up and to keep up the pace. As the column entered Gainesville, it was joined by J E. B. Stuart and the rest of his cavalry division. The presence of the larger cavalry force allowed a relaxation in the march discipline. Jackson then headed south from Gainesville to Bristoe Station, located on the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, Pope's line of communication.

His cavalry van arrived at sunset in time to interdict three Federal supply trains after tearing up the tracks and cutting the telegraph wires. Isaac Trimble's brigade of Ewell's Division, along with Stuart's cavalry, advanced eastward along the railroad later that night to the Federal supply depot at Manassas Junction. They secured that place by 2400, taking over 300 prisoners in the process.

In the meantime, Longstreet's wing had begun to follow Jackson's forces, pulling out of its Rappahannock positions by midmorning and leaving only Brig. Gen. R. H. Anderson's Division to divert Pope. Lee and Longstreet had considered forcing the river crossings and reuniting with Jackson by the most direct route but disregarded doing so as impracticable. Moving somewhat more cautiously because of the absence of cavalry, Longstreet camped the night of the twenty-sixth at Orleans, 11 miles from his starting point.

Continued cavalry reports of these movements to the northwest persuaded General Pope to send out on the afternoon of the twenty-sixth a larger cavalry force under Brig. Gen. John Buford to investigate. The Army of Virginia was still deployed to defend the Rappahannock crossings.

Major General Irvin McDowell's III Corps had one division (Ricketts') four miles from Warrenton on the Waterloo Road, one (Reynolds') in Warrenton, and one (King's) around Sulphur Springs. The forward divisions continued to engage the Confederates with artillery. Major General Franz Sigel's I Corps remained camped around Warrenton, and Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks' II Corps, still recovering from the 9 August fight near Culpeper, was at Fayetteville (modem Opal). Heintzelman's III Corps was joined by Reno's small corps near Pope's headquarters at Warrenton Junction.

Morrel's 1st Division of Porter's V Corps was at Kelly's Ford on the lower Rappahannock, while Porter's other division, commanded by Maj. Gen. George Sykes was 6 miles east of Bealeton along the railroad. Some of Buford's scouts early in the evening reported a large force moving through Thoroughfare Gap in the Bull Run Mountains, well to the northeast. This information, plus the loss of communications to the east along the railroad, led General Pope about 2000 to direct his forces to redeploy to the Gainesville area. Preparations went on through the night, but there was little movement until the next day.

Very early on the twenty-seventh, Jackson sent A. P. Hill's and Taliaferro's Divisions to consolidate Trimble's and Stuart's hold on the vast Manassas supply dumps. Ewell's Division, with its three brigades, was left at Bristoe as a rearguard with orders to fall back on the main force if hard pressed. The main force, in the meantime, devoted itself to helping itself to the tons of Federal supplies in the dumps and boxcars at the Manassas junction.

At about 1000, the New Jersey Brigade of Slocum's Division, VI Corps, approached Manassas under Brig. Gen. George Taylor, east from the direction of Union Mills. Jackson ultimately deployed most of A. P. Hill's Division to confront this threat. The veteran Journeymen detrained north of the railroad bridge and advanced toward Manassas, apparently expecting to disperse a raiding force. They gallantly pressed against Hill's fire until forced to retreat at about 1100 with heavy losses. General Taylor was mortally wounded, pleading with his officers "for God's sake to prevent another Bull Run." The Confederate infantry pursued up to the railroad bridge, then returned to join in the ransacking of the depot, while Rebel cavalry pressed the hapless Federals all the way back to Fairfax Courthouse.

At sundown, Ewell brought his division back to Manassas after contending briskly at Bristoe with Hooker's Division of Heintzelman's Corps throughout the afternoon. The full Confederate force evacuated Manassas Junction late that night after destroying everything it could not eat or carry away. Each of the Confederate divisions took different routes to their new location on the old battlefield, 7 miles to the north of Manassas.

Taliaferro moved directly north up Sudley Springs Road. A. P. Hill crossed Bull Run at Blackburn's Ford and marched to Centreville, where at 1000 on the twenty-eighth, he turned west on the Warrenton Pike to the old battlefield.

Ewell, the last to leave, also crossed at Blackburn's Ford but then followed the north bank of Bull Run until he reached the bridge on the Warrenton Pike, where he also turned westward onto the old battlefield. The march was attended with some confusion as Jackson had not been clear as to his plans or his corps' destination. The multiple routes also thoroughly confused General Pope as to his enemy's location and intentions.

Longstreet continued his progress eastward throughout the twenty-seventh. A Federal cavalry patrol rode into his van during a midday rest stop at Salem. Buford's blue horsemen aggressively demonstrated, threatening Lee and his headquarters, then pulled out of town.

The size and intentions of the Federal cavalry force could not be determined by Longstreet without cavalry of his own. Consequently, the Confederate move thereafter was even more cautious than before, arriving at White Plains late at night for its second halt.

Pope's forces had begun moving about 0800 on the twenty-seventh. McDowell's and Sigel's Corps moved to the vicinity of New Baltimore and Buckland Mills. In the latter place, Brig. Gen. Robert Milroy's Brigade saved the bridge from destruction by Confederate cavalry in a brisk firefight. Late in the day, Milroy's Brigade and another of Sigel's units, Brig. Gen. Carl Schurz's Division moved eastward into Gainesville. Reno's Corps, along with Kearny's Division, deployed to Greenwich to be in a supporting position.

Major General Joseph Hooker began moving his division early in the day eastward down the railroad. This was the unit that collided at 1400 at Kettle Run near Bristoe Station with Ewell's Division, which it pressed back effectively until Ewell withdrew.

Pope arrived at Bristoe Station that night. He assumed Jackson was "in the bag" at Manassas and directed his forces to concentrate there. He thus removed them from excellent blocking positions, opening the way for the rest of the Confederate Army to join Jackson in the vicinity of Groveton. His plan overlooked the need to keep Lee's two wings separated. The Gainesville position was key and should have been held until Southern deployment and intentions were understood fully.

Earlier, General McDowell had placed his and Sigel's units around Haymarket and Gainesville and as far west as New Baltimore. He also had sent out the cavalry forces that caused Lee and Longstreet problems, incidentally confirming their imminent arrival. On his own responsibility, at about 1500, he forwarded James B. Ricketts' Division to block Thoroughfare Gap while probing eastward with another division looking for Jackson. He seemed to be forming a realistic picture of the situation. However, later, McDowell had to redeploy in response to Pope's orders, leaving Ricketts behind, unsupported.

The forces of Porter, Reno, and Heintzelman were concentrated at Bristoe by midmorning of the twenty-eighth. Banks' Corps guarded the army's trains at Catlett Station.

Contact Resumed

Jackson's command was reunited by 1200 on 28 August in the vicinity of the junction of the Warrenton Pike and the Sudley Springs Road. Later, he moved it farther northwest past the hamlet of Groveton in response to reports of Federal troop movements. The Confederates established themselves on a ridge running southwest to northeast, which was protected on its eastern side by the trenches and banks of an unfinished railroad. The position promised to allow linkage with Longstreet's Corps approaching from Thoroughfare Gap and Gainesville.

It also provided access to the Aldie Gap, eight miles to the northwest, as an escape route if the two wings of Lee's army failed to connect. It was an excellent defensive position from which to challenge Pope's forces. Jackson's men rested in the summer shade while Pope's Divisions sought them out. Finally, late in the day, Stonewall saw the right moment to reveal his presence and bring on the battle envisaged by General Lee.

The Federal movements throughout the day had been floundering and cumbersome. In McDowell's area, General Sigel misunderstood the orders requiring his left flank to move along the east-to-west Manassas Gap Railroad instead of plunging southward to align on the more north-to-south Orange and Alexandria Railroad.

Sigel further impeded the movement of McDowell's elements with his trains, which he had retained despite orders to the contrary. Reynolds' Division finally headed east from Gainesville along the Warrenton Pike in mid-morning. At about 1000, it encountered a Confederate brigade led by Brig. Gen. Bradley T. Johnson of Taliaferro's Division, Jackson's Corps, near the junction of the Pike and Pageland Lane. John Reynolds deployed Meade's Brigade with a battery, and a brisk exchange of fire ensued until Johnson broke contact. Reynolds assumed he had brushed a reconnaissance force and proceeded down Pageland Lane toward Manassas as ordered without taking further action.

Meanwhile, U.S. cavalry picked up Confederate stragglers on the road to Centreville. General Pope weighed the information of Jackson's multiple departure routes and decided that his opponent was at Centreville. Accordingly, at about 1200, he issued new orders directing everyone to move to that village. Heintzelman's Corps slogged directly through Manassas Junction. Kearny, in the lead, reached Centreville late in the afternoon, in time to engage briefly a regiment of Confederate cavalry screening the Warrenton Pike west of the village.

Reno's Corps bivouacked between Centreville and Blackburn's Ford while Pope set up with Hooker's Division near the Ford. Elsewhere, Sigel started north on the Sudley Springs Road en route to Centreville. McDowell split his corps, Reynolds continuing down Pageland Lane while Brig. Gen. Rufus King, just turned off the Pike, was ordered to backtrack and head west on the Pike itself toward Centreville.

Late in the afternoon, Pope had learned from McDowell of Longstreet's presence at White Plains but still assumed he had sufficient time to deal with Jackson alone. This would not prove to be the case, however. Longstreet had moved out early on the twenty-seventh, his lead units reaching Thoroughfare Gap by 1500. There, Brig. Gen. G. T Anderson's Georgia Brigade encountered Ricketts' Federals blocking the passage.

While John B. Hood's Texas Brigade probed local trails to support Anderson and to flank the Federals, Wilcox's Division made a longer flanking movement through Hopewell Gap three miles to the north. Hood's force succeeded in turning Ricketts' flank about sunset, forcing him to withdraw. By 2200, the bulk of Longstreet's force had moved through the Gap and was in camps as far east as Haymarket.

Well before that, Jackson had revealed his position to prevent what he assumed was a general Federal withdrawal to the Centreville area. King's Division had succeeded in reversing its course and by 1700 was heading east on the Warrenton Pike, unknowingly proceeding across Jackson's right flank and front, near Brawner's Farm, a mile west of Groveton. Naturally ignorant of the absence of Federal coordination, Jackson assumed King was Pope's north flank guard and had to be attacked before the whole Federal force escaped.

The ensuing fight was one of the most brutal of the war. Two of Jackson's Divisions engaged in a slugging match with Brig. Gen. John Gibbon's Brigade and elements of Brig. Gen. Abner Doubleday's. Each side valiantly exchanged volleys in the growing darkness, sometimes at ranges of 100 yards or less. Losses were high on both sides, but especially damaging to Jackson was the wounding of two division commanders, Ewell and Taliaferro.

The fighting died down by about 2100. By that time, however, Sigel and Reynolds had moved to the sound of the guns, brushed aside some of Jackson's vedettes, and set up on the old battlefield north and south of Henry Hill.

Generals King and Ricketts, out of touch with each other and their superiors, had experienced rough handling from larger Confederate forces. Neither knew what Pope's intentions were, and both were unable to find General McDowell, their corps commander.

He had gone to confer with the Pope, got lost in the woods, and did not appear again until the following morning. The importance of their position was not apparent to either general. Consequently, in the absence of any guidance, both decided, on their own, to withdraw, Ricketts moving to Bristoe Station and King to Manassas.

The way was now fully clear for Longstreet to reunite with Jackson. Pope, however, continued to disregard Longstreet's presence. Instead, he read into the facts on hand, his own version of reality. He considered A. P. Hill's withdrawal westward from Centreville was an indicator that Jackson was retreating. He learned of the Brawner's Farm fight by 2100 and again assumed it was the rearguard action of a retreating enemy. As a result, he changed his orders again, directing all his forces to head for the old Manassas Battlefield to go in for the kill on Jackson's presumably retreating force.

By this time, most of the Federal units had been marching hither and yon since late on the twenty-sixth without rations or a clear idea of their objective. Pope ignored their plight, compounding their problems with poor staff work. An example of this with serious consequences was the orders to General Porter.

He was directed on the afternoon of 28 August to move his corps then at Bristoe to the old battlefield by way of Centreville. Porter complied, but when his force had reached Blackburn's Ford on the morning of 29 August, Pope told him to turn about and move to Gainesville by way of Manassas. This was Pope's reaction to the news of King and Ricketts' withdrawal. Earlier, it will be seen. Pope had directed Sigel on the old battlefield to fix Jackson until everyone else could converge.

Porter got as far as Dawkin's Branch, about two miles northwest of Manassas Junction, about 1100, 29 August. He had, in the meantime, rendezvoused with General McDowell. The two men then received an additional order addressed jointly to them from Pope, which told them to get to Gainesville, to link with the forces to the north, to be prepared to fall back on Centreville and to use their own discretion.

Porter chose to remain in place, observing a growing Confederate force in front of him. McDowell took his corps northward on the Sudley Springs Road to try to establish contact, but neither general was clear as to what he should do. Pope continued to focus exclusively on Jackson while ignoring the growing evidence that Longstreet was nearby.

The Battle Begins

The twenty-ninth of August had opened hot and bright with Sigel's Corps (Schenck's Division, Schurz's Division, and Milroy's Brigade) bivouacked in the vicinity of the Sudley Springs Road-Warrenton Pike. Reynolds' Division was farther south near the old village of New Market. He had sent patrols nearly as far west as Groveton. General Sigel, responding to Pope's orders to fix the allegedly fleeing Jackson, quickly pressed an attack. By 0500 on 29 August, all the forces at his disposal were in a movement to contact.

Jackson was hardly leaving. His forces were set up in the positions he had selected along the old railroad bed and the ridge behind it. The Confederate right starting around Brawner's Farm was occupied by Jackson's old division, now commanded by Brig. Gen. William E. Starke, who had replaced the wounded Taliaferro.

The center was defended by Ewell's Division, commanded now by Brig. Gen. Alexander R. Lawton in place of the grievously wounded Ewell. The left, or northern, flank was held by A. P. Hill's Light Division almost up to the Sudley Springs.

The Federals attacked all along the line. Nowhere had they built depth enough to exploit any local successes. Neither were their assaults coordinated sufficiently to support each other. As a result, Jackson was able to move reserves to each threatened point without concern for any gaps he may have created. These disjointed efforts were well fought at the unit level and did succeed in pressing Jackson's men back into their main lines along the old railroad. By 1000, the Federal forces were exhausted, and Sigel called a halt for reorganization and to await reinforcements.

About the same time, Longstreet's Corps had arrived and was moving into line south of Jackson's position. It had made contact with Stuart's Cavalry early in the morning between Haymarket and Gainesville. Elements of the cavalry deployed on Longstreet's southern flank, enabling him to move his force rapidly to the sound of the guns with less concern for security.

A little after 1000, Hood's Division came into Jackson's view and deployed to the right of his corps in line on both sides of the Pike just east of its intersection with Pageland Lane. Hood's Batteries and the Washington Artillery deployed on Jackson's immediate right to provide him additional fire support. Wilcox's Division was echeloned to Hood's left rear north of the Pike, while Kemper's Division was echeloned to his right rear southward. D. R. Jones' Division extended from Kemper's farther south across the Manassas Gap Railroad, and Robertson's Cavalry Brigade screened toward Manassas.

It was these forces that Porter had noted as his lead division (Morell's) approached Dawkin's Branch. Ironically, each was arriving on the scene at about the same time. Porter was possibly inspired to greater caution, not realizing that part of the large dust cloud he noted was caused by Stuart's cavalry dragging bushes on the roads to deceive any observers and to give D. R. Jones more time to get in place.

Porter immediately set up a skirmish line and deployed some of his artillery, which exchanged fire with the Confederates for the rest of the day. His presence bred sufficient caution in Longstreet twice to successfully contest Lee's suggestion that he launch a corps attack. In 1800, Pope, in turn, directed Porter to launch an attack, but then later changed his mind and ordered Porter to the main battle instead, still ignoring Longstreet's presence.

While this drama had been going on in the South, the pressure on Jackson had been renewed dangerously. Pope arrived on the scene from Centreville about noon, bringing with him Heintzelman's Corps (Kearny's and Hooker's Divisions) and Reno's Corps (Reno's and Stevens' Divisions).

The fresh troops deployed from the Stone House area into the northern part of the line. While they were doing this, elements of Schurz's Division attacked at 1200 and seized and held part of the old railroad until relieved by Heintzelman's Corps at about 1400. Several hours of regrouping and rest followed before the assaults were renewed. Then, Pope directed Heintzelman to attack with both his divisions. Unfortunately, the assault was again uncoordinated.

In 1600 Grover's Brigade of Hooker's Division made a legendary bayonet assault against the center of Jackson's line. Five hundred men were lost in 20 minutes to no avail because the lack of reserves prevented exploitation of the Federal penetration, and Grover was forced to withdraw.

Two hours later, Kearny's Division, with Stevens' Division in support, finally launched its attack against Jackson's extreme left (north). The Federals threatened to roll up that part of the line held by Brig. Gen. Maxcy Gregg's South Carolina Brigade of A. P. Hill's Division, but were stopped and repulsed by Lawton's and Early's Brigades of Ewell's Division hustled from less threatened portions of the Confederate line.

As this fighting was dying down, General McDowell arrived with his lead division, Hatch's (formerly King's), with Ricketts' Division about an hour behind. Pope was convinced that some adjustments Jackson was making to his line presaged a withdrawal. Thus, in 1730, he ordered Hatch to pursue. Ironically, at the same time, General Lee had suggested a probe of some sort to Longstreet. The latter agreed to reconnaissance by Hood's Division. Thus, in about 1830, Hatch's Division collided with Hood's in the vicinity of Groveton.

Fighting endured around the crossroads until about 2015, when Hatch was compelled to withdraw. Reynolds' Division south of the Pike had been prevented from supporting effectively by Longstreet's artillery. Pope continued to ignore news of Longstreet's presence in strength, treating Porter's evidence on his arrival from Dawkin's Branch merely as excuses for the latter's inactivity.

The redeployment of Porter on the evening of the twenty-ninth meant that Longstreet was free for the next day, despite Pope's fatuous assessment of the day's events as a great victory. In fact, Confederate strength had grown further with the arrival of about 2400 of R. H. Anderson's Division from the old Rappahannock line.

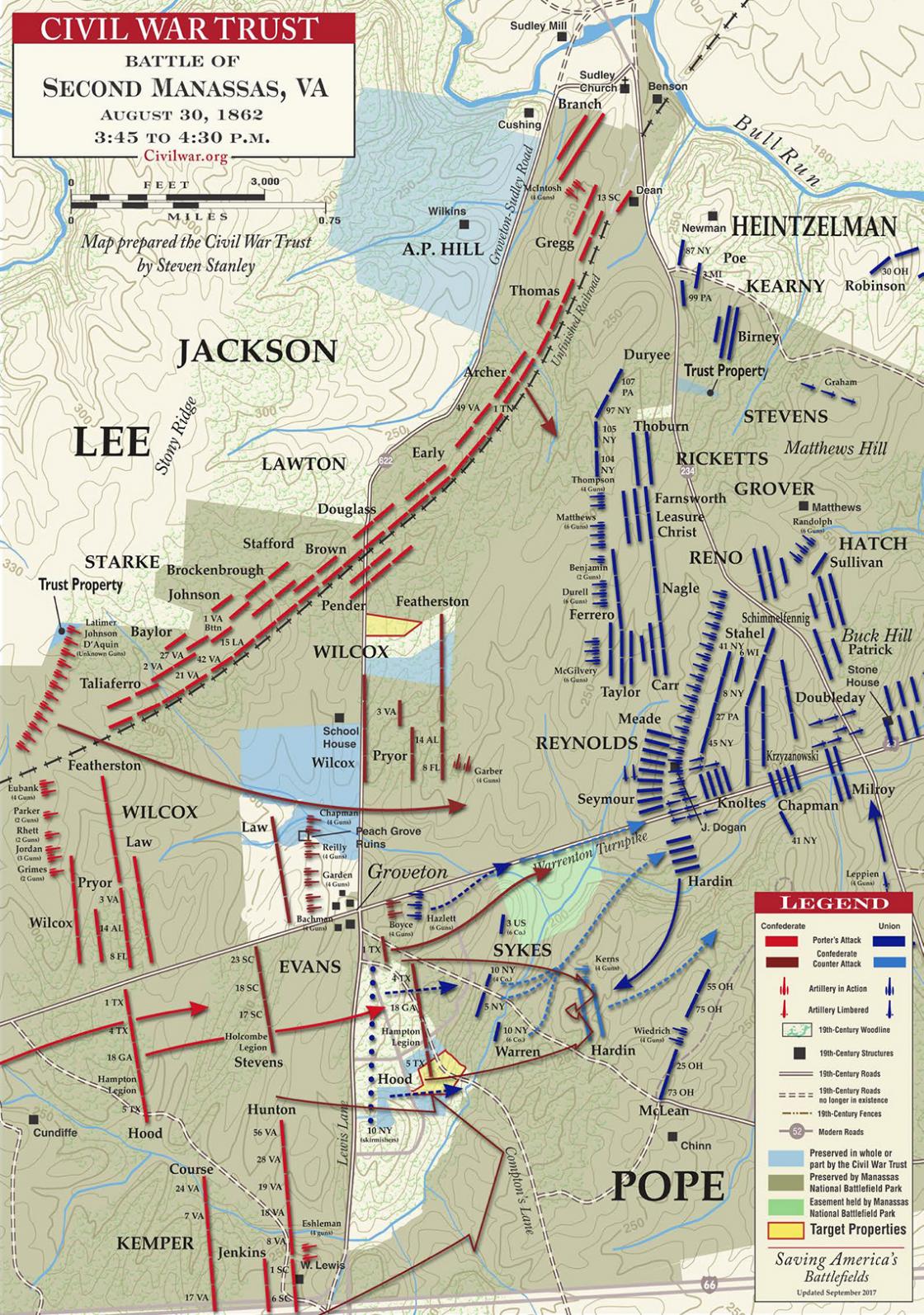

The thirtieth of August also dawned hot and dry as both armies eyed each other warily. At about 0800, Federal artillery opened up vigorously, and Maj. S. D. Lee's 18-gun battalion was wheeled onto the right of Jackson's line to reply. Within an hour, firing on both sides died down in favor of an uncanny summer morning silence.

Lee and his corps commanders conferred at his command post on a hill near the corps coordinating point. They concluded that the Federals had had enough, and the battle was probably over. They discussed plans for what to do next before the officers returned to the commands. Then, at noon, additional Federal artillery began rolling into view, followed by waves of infantry. Obviously, another attack loomed.

Pope planned to attack Jackson's position on the north side of the Warrenton Pike. He left only Reynolds' Division to secure his left flank opposite Longstreet, whose presence he continued to disregard. General Porter was to conduct the main attack with Hatch's and Morell's Divisions while Heintzelman's Corps supported on the right (north). At 1500, the two divisions, with Sykes' in support, commenced the main attack, with Butterfield's Brigade of Morell's Division to the south.

The first Federal wave actually reached Jackson's desperate defenders along the old railroad bed. More waves approached, and Jackson signaled to Lee that he needed help. Longstreet had been sizing up the situation on Jackson's flank. He directed Stephen D. Lee's eighteen guns to enfilade the advancing Federals about the same time he received orders from Lee to help Jackson.

This fire from their left (south) quickly shattered the Federal lines, forcing them to withdraw. Meanwhile, Heintzelman's units fought briskly with A. P. Hill's to the north.

About 1530, Pope directed Reynolds to leave his position on Chinn's Ridge south of the Pike and move to back up Porter's shattered divisions. Reynolds objected to no avail. His departure left only Warren's Brigade (Sykes' Division), supporting a single battery south of the Pike to confront Longstreet. Warren, on his own, had moved into a position previously occupied by Reynolds when the latter had shifted to Chinn's Ridge on orders from General McDowell.

The Confederate advance

Almost simultaneously, Lee and Longstreet saw their opportunity. The latter was giving orders for his whole line to advance about the time he received orders from Lee to do so. About 1545, Longstreet's Corps attacked, pivoting on Jackson's position. Lee ordered Jackson "to look out for and protect his [Longstreet's] left flank." Hood's Division advanced at the pivot along an axis formed by the Pike while Longstreet's other units attacked in a great arc north-northeast.

Hood made contact within 150 yards of his start but quickly overwhelmed the fierce resistance offered by Warren's little brigade a few hundred yards southeast of Groveton. Pope was to be fortunate in the quality of fighting demonstrated by those of his units hurled in to oppose Longstreet.

Hood advanced a few hundred yards farther, where he was resisted by Anderson's Brigade and Kerns' Battery of Reynolds' Division, caught while shifting to the north. Jackson's tired force had not pressed at the same pace, allowing the Federal buildup of an artillery line to remain north of the Pike. This fire greatly impeded Hood's progress as he approached Chinn's Ridge (Bald Hill) and ultimately prevented any significant Confederate moves north of the Pike.

The developing crises were recognized quickly by McDowell and Pope. While Warren and Anderson sacrificed themselves, the generals rushed units to Chinn's Ridge and to Henry Hill. Sigel covered the withdrawal of Porter's Corps, concurrently sending two brigades from Schurz's Division south of the Pike.

These were reinforced by two brigades from Ricketts' Division marched down from the northern edge of the battlefield. A desperate battle developed on Chinn's Ridge as wave after wave of Federals, each arriving just in time, beat back the attacking Confederates. By this time, Kemper's and D. R. Jones' Divisions had supplanted Hood's. The time bought on Chinn's Ridge allowed Milroy's Brigade, Reynolds' Division, and Sykes' Division to establish themselves in a defensive position along the Sudley Springs Road on the west side of Henry Hill.

Union Retreat

The Confederates pushed the last Federal defender off Chinn's Ridge at about 1800 and charged against this final Federal line. The approach of D. R. Jones' Division from the south forced the Federals to extend and refuse their southern flank. Their line held, however. These defenders were relieved by elements of Reno's Corps about 1930.

They repulsed one final Confederate effort in the darkness. Then, about 2030, all was quiet except for the groans of the injured. Pope ordered Banks at Bristoe to save what trains he could and to evacuate. He also directed his forces at hand to withdraw to Centreville, which they did in reasonably good order. Schurz's Division was the last out, leapfrogging rearward from high ground to high ground. It vacated a final bridgehead west of the Bull Run Bridge at 2300, destroying the bridge itself two hours later.

The Second Battle of Manassas was over. In an aftershock at Chantilly on 1 September, Kearny and Stevens were killed. But then Pope's battered army withdrew to the safety of the defenses of Washington, and Lee's thoughts shifted to consider an invasion of Maryland to seal his summer triumphs. In less than three weeks, he was to fight the great battle of Antietam, quickly overshadowing the achievements and failures on the Plains of Manassas.

Aftermath

The operational lapses shown by both forces reflect the greenness of the two opposing armies. These lapses underline the point that the ablest commander is constrained in his achievements by the quality, training, and professionalism of the units he commands. Armies grow; they cannot be created on demand.

Robert E. Lee's leadership and command relationships developed much greater responsiveness in his force. The rank and file on both sides were equally sound. The difference between the two armies lay in the quality of their senior leaders and how they dealt with each other. Ironically, aspects of trust affected both forces.

Pope lost at Second Manassas because he refused to trust his subordinates; Lee lost a chance for a decisive blow on 29 August because he trusted Longstreet's cautious judgment too much.

General Lee capitalized on the strengths of the Army of Northern Virginia and its leaders, completely reversing the strategic situation in a matter of months. Seemingly trapped between McClellan and Pope at Richmond, he took advantage of the opportunities offered by Federal mistakes to relieve that city while moving to threaten his enemy's capital.

This shift further reserved to the Confederacy for another season the assets of a large part of Virginia hitherto occupied. It also paved the way for Lee's first invasion of the North as he retained the strategic initiative.

The hapless Pope was relieved shortly thereafter and sent to command a department in Minnesota and the Dakotas. His brief career in command of the Army of Virginia is pitilessly summarized by the historian of the U.S. II Corps:

"The braggart who had begun his campaign with insolent reflections ... had been kicked, cuffed, hustled about, knocked down, run over, and trodden upon as rarely happens in the history of war. His communications had been cut; his headquarters pillaged; a corps had marched into his rear and had encamped at its ease upon the railroad by which he received his supplies; he had been beaten or foiled in every attempt he had made to 'bag' those defiant intruders; and, in the end, he was glad to find refuge in the entrenchments of Washington."

Understanding the failures of this not unable but flawed leader may be the most valuable legacy of Second Manassas.