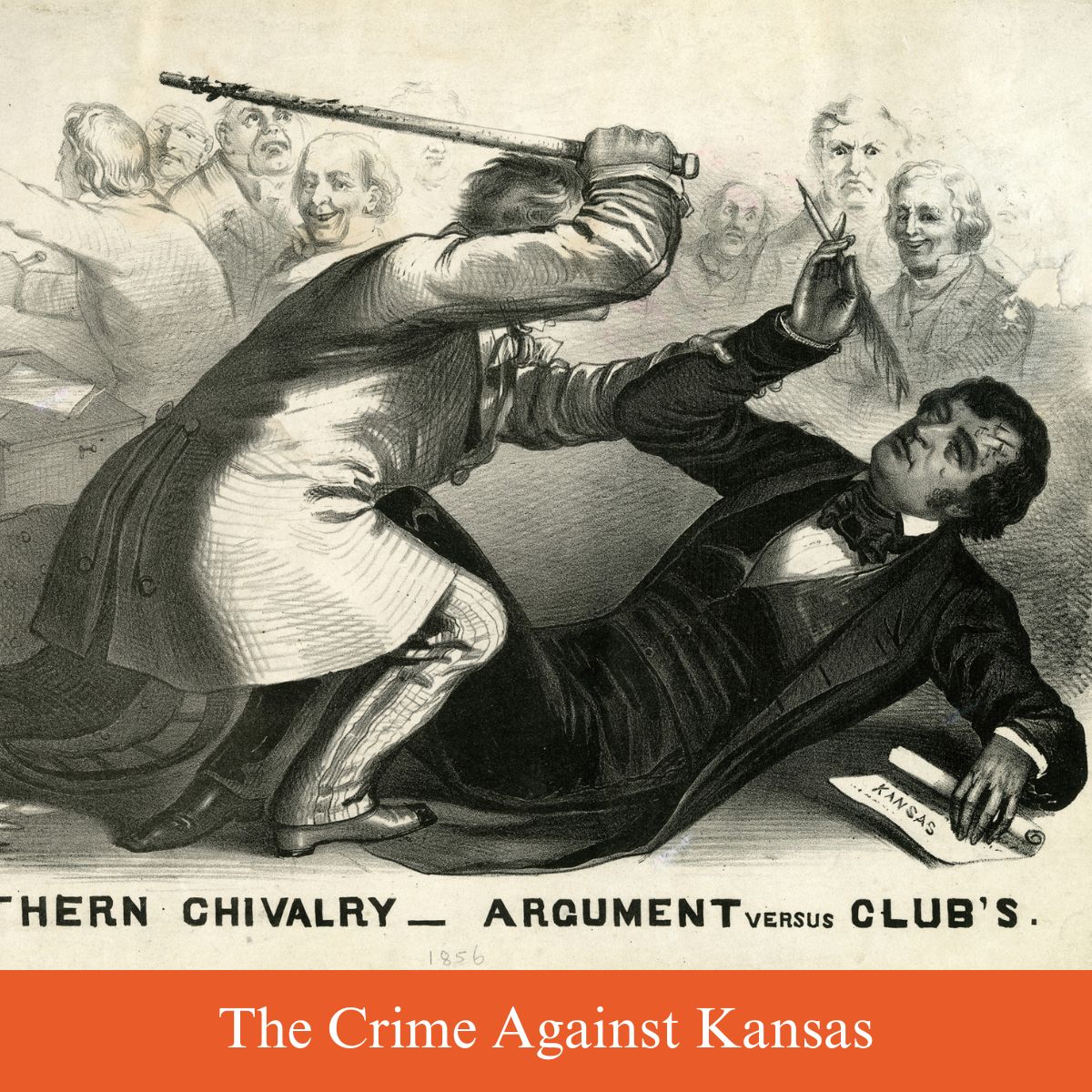

This speech was delivered by Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts on May 19-20, 1856, in the United States Senate. A few days later, Congressman Preston Brooks of South Carolina, a cousin of Sen. Andrew Butler, whom Sumner ridiculed in this speech, beat Sumner senseless with his cane on the floor of the Senate.

MR. PRESIDENT:

You are now called to redress a great transgression. Seldom in the history of nations has such a question been presented. Tariffs, Army bills, Navy bills, and Land bills are important and justly occupy your care, but these all belong to the course of ordinary legislation. As means and instruments only, they are necessarily subordinate to the conservation of government itself. Grant them or deny them, in greater or less degree, and you will inflict no shock. The machinery of government will continue to move. The State will not cease to exist. Far otherwise is it with the eminent question now before you, involving, as it does, Liberty in a broad territory and also involving the peace of the whole country, with our good name in history forever more.

Take down your map, sir, and you will find that the Territory of Kansas, more than any other region, occupies the middle spot of North America, equally distant from the Atlantic on the east and the Pacific on the west, from the frozen waters of Hudson's Bay on the north, and the tepid Gulf Stream on the south, constituting the precise territorial center of the whole vast continent. To such advantages of situation, on the very highway between two oceans, is added a soil of unsurpassed richness and fascinating, undulating beauty of surface, with a health-giving climate, calculated to nurture a powerful and generous people, worthy to be a central pivot of American institutions. A few short months only have passed since this spacious and Mediterranean country was open only to the savage who ran wild in its woods and prairies, and now it has already drawn to its bosom a population of freemen larger than Athens crowded within her historic gates, when her sons, under Miltiades, won liberty for mankind on the field of Marathon; more than Sparta contained when she ruled Greece, and sent forth her devoted children, quickened by a mother's benediction, to return with their shields, or on them; more than Rome gathered on her seven hills, when, under her kings, she commenced that sovereign sway, which afterward embraced the whole earth; more than London held, when, on the fields of Crecy and Agincourt, the English banner was carried victoriously over the chivalrous hosts of France.

Against this Territory, thus fortunate in position and population, a crime has been committed, which is without example in the records of the past. Not in plundered provinces or in the cruelties of selfish governors will you find its parallel, and yet there is an ancient instance which may show at least the path of justice. In the terrible impeachment by which the great Roman orator has blasted through all time the name of Verres, amidst charges of robbery and sacrilege, the enormity which most aroused the indignant voice of his accuser, and which still stands forth with strongest distinctness, arresting the sympathetic indignation of all who read the story, is, that away in Sicily he had scourged a citizen of Rome that the cry, "I am a Roman citizen," had been interposed in vain against the lash of the tyrant governor. Other charges were that he had carried away productions of art and that he had violated the sacred shrines. It was in the presence of the Roman Senate that this arraignment proceeded; in a temple of the Forum amidst crowds such as no orator had ever before drawn together thronging the porticos and colonnades, even clinging to the housetops and neighboring slopes, and under the anxious gaze of witnesses summoned from the scene of a crime. But an audience grander far, of higher dignity, of more various people, and of wider intelligence, the countless multitude of succeeding generations, in every land, where eloquence has been studied, or where the Roman name has been recognized, has listened to the accusation and throbbed with condemnation of the criminal. Sir, speaking in an age of light and a land of constitutional liberty, where the safeguards of elections are justly placed among the highest triumphs of civilization, I fearlessly assert that the wrongs of much abused Sicily, thus memorable in history, were small by the side of the wrongs of Kansas, where the very shrines of popular institutions, more sacred than any heathen altar, have been desecrated... where the ballot-box, more precious than any work, in ivory or marble, from the cunning hand of art, has been plundered... and where the cry, "I am an American citizen," has been interposed in vain against outrage of every kind, even upon life itself. Are you against sacrilege? I present it for your execration. Are you against robbery? I hold it up to your scorn. Are you for the protection of American citizens? I show you how their dearest rights have been cloven down while a Tyrannical Usurpation has sought to install itself on their very necks!

But the wickedness which I now begin to expose is immeasurably aggravated by the motive which prompted it. Not in any common lust for power did this uncommon tragedy have its origin. It is the rape of a virgin Territory, compelling it to the hateful embrace of Slavery, and it may be clearly traced to a depraved longing for a new slave State, the hideous offspring of such a crime, in the hope of adding to the power of slavery in the National Government. Yes, sir, when the whole world, alike Christian and Turk, is rising up to condemn this wrong and to make it a hissing to the nations, here in our Republic, force, aye, sir, FORCE has been openly employed in compelling Kansas to this pollution, and all for the sake of political power. There is a simple fact, which you will in vain attempt to deny, but which in itself presents an essential wickedness that makes other public crimes seem like public virtues.

But this enormity, vast beyond comparison, swells to dimensions of wickedness which the imagination toils in vain to grasp when it is understood that for this purpose are hazarded the horrors of intestine feud not only in this distant Territory but everywhere throughout the country. Already, the muster has begun. The strife is no longer local but national. Even now, while I speak, portents hang on all the arches of the horizon, threatening to darken the broad land, which already yawns with the mutterings of civil war. The fury of the propagandists of Slavery and the calm determination of their opponents are now diffused from the distant Territory over widespread communities and the whole country, in all its extent marshaling hostile divisions and foreshadowing strife which, unless happily averted by the triumph of Freedom, will become war fratricidal, parricidal war with an accumulated wickedness beyond the wickedness of any war in human annals; justly provoking the avenging judgment of Providence and the avenging pen of history, and constituting strife, in the language of the ancient writer, more than foreign, more than social, more than civil; but something compounded of all these strifes, and in itself more than war; sed potius commune quad dam ex omnibus, et plus quam bellum.

Such is the crime which you are to judge. But the criminal also must be dragged into a day, that you may see and measure the power by which all this wrong is sustained. From no common source could it proceed. In its perpetration was needed a spirit of vaulting ambition which would hesitate at nothing; a hard). hood of purpose which was insensible to the judgment of mankind; a madness for Slavery which would disregard the Constitution, the laws, and all the great examples of our history; also a consciousness of power such as comes from the habit of power; a combination of energies found only in a hundred arms directed by a hundred eyes; a control of public opinion through venal pens and a prostituted press; an ability to subsidize crowds in every vocation of life, the politician with his local importance, the lawyer with his subtle tongue, and even the authority of the judge on the bench; and a familiar use of men in places high and low, so that none, from the President to the lowest border postmaster, should decline to be its tool; all these things and more were needed, and they were found in the slave power of our Republic. There, sir, stands the criminal, all unmasked before you, heartless, grasping, and tyrannical, with an audacity beyond that of Verres, a subtlety beyond that of Machiavel, a meanness beyond that of Bacon, and an ability beyond that of Hastings. Justice to Kansas can be secured only by the prostration of this influence; for this the power behind greater than any President which succors and sustains the crime. Nay, the proceedings I now arraign derive their fearful consequences only from this connection.

In now opening this great matter, I am not insensible to the austere demands of the occasion, but the dependence of the crime against Kansas upon the slave power is so peculiar and important that I trust to be pardoned while I impress it with an illustration, which to some may seem trivial. It is related in Northern mythology that the god of Force, visiting an enchanted region, was challenged by his royal entertainer to what seemed a humble feat of strength merely, sir, to lift a cat from the ground. The god smiled at the challenge and, calmly placing his hand under the belly of the animal, with superhuman strength, strove while the back of the feline monster arched far upward, even beyond reach, and one paw actually forsook the earth, until last the discomfited divinity desisted; but he was little surprised at his defeat when he learned that this creature, which seemed to be a cat, and nothing more, was not merely a cat, but that it belonged to and was a part of the great Terrestrial Serpent, which, in its innumerable folds, encircled the whole globe. Even so, the creature, whose paws are now fastened upon Kansas, whatever it may seem to be, constitutes, in reality, a part of the slave power, which, in its loathsome folds, is now coiled about the whole land. Thus, I expose the extent of the present contest, where we encounter not merely local resistance but also the unconquered sustaining arm behind. But out of the vastness of the crime attempted, with all its woe and shame, I derive a well-founded assurance of a commensurate vastness of effort against it by the aroused masses of the country, determined not only to vindicate Right against Wrong but to redeem the Republic from the thraldom of that Oligarchy which prompts, directs, and concentrates the distant wrong.

Such is the crime, and such the criminal, which it is my duty in this debate to expose, and, by the blessing of God, this duty shall be done completely to the end.

But, before entering upon the argument, I must say something of a general character, particularly in response to what has fallen from Senators who have raised themselves to eminence on this floor in the championship of human wrongs. I mean the Senator from South Carolina (Mr. Butler) and the Senator from Illinois (Mr. Douglas), who, though unlike Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, yet like this couple, sally forth together in the same adventure. I regret much to miss the elder Senator from his seat, but the cause, against which he has run a tilt, with such activity of animosity, demands that the opportunity of exposing him should not be lost, and it is for the cause that I speak. The Senator from South Carolina has read many books of chivalry and believes himself a chivalrous knight, with sentimcuts of honor and courage. Of course, he has chosen a mistress to whom he has made his vows and who, though ugly to others, is always lovely to him; though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight, I mean the harlot, Slavery. For her, his tongue is always profuse in words. Let her be impeached in character or any proposition made to shut her out from the extension of her wantonness, and no extravagance of manner or hardihood of assertion is then too great for this Senator. The frenzy of Don Quixote, on behalf of his wench, Dulcinea del Toboso, is all surpassed. The asserted rights of Slavery, which shock equality of all kinds, are cloaked by a fantastic claim of equality. If the slave States cannot enjoy what, in mockery of the great fathers of the Republic, he misnames equality under the Constitution, in other words, the full power in the National Territories to compel fellowmen to unpaid toil, to separate husband and wife, and to sell little children at the auction block then, sir, the chivalric Senator will conduct the State of South Carolina out of the Union! Heroic knight! Exalted Senator! Second, Moses came for a second exodus!

But not content with this poor menace, which we have been twice told was " measured," the Senator, in the unrestrained chivalry of his nature, has undertaken to apply opprobrious words to those who differ from him on this floor. He calls them "sectional and fanatical," and opposition to the usurpation in Kansas he denounces as "an uncalculating fanaticism." To be sure, these charges lack all grace of originality and all sentiment of truth, but the adventurous Senator does not hesitate. He is the uncompromising, unblushing representative on this floor of a flagrant sectionalism, which now domineers over the Republic, and yet with a ludicrous ignorance of his own position, unable to see himself as others see him or with an effrontery which even his white head ought not to protect from rebuke, he applies to those here who resist his sectionalism the very epithet which designates himself. The man who strive to bring the government back to its original policy, when Freedom and not Slavery was sectional, he arraigns as sectional. This will not do. It involves too great a perversion of terms. I tell that Senator that it is to him self and to the "organization" of which he is the "committed advocate" that this epithet belongs. I now fasten it upon them. For myself, I care little for names, but since the question has been raised here, I affirm that the Republican party of the Union is in no just sense sectional, but, more than any other party, national, and that it now goes forth to dislodge from the high places of the Government the tyrannical sectionalism of which the Senator from South Carolina is one of the maddest zealots.

As the Senator from South Carolina is Don Quixote, the Senator from Illinois (Mr. Douglas) is the Squire of Slavery, its very Sancho Panza, ready to do all its humiliating offices. This Senator, in his labored address, vindicating his labored report, piling one mass of elaborate error upon another mass constrained himself, as you will remember, to unfamiliar decencies of speech. Of that address, I have nothing to say at this moment, though before I sit down, I shall show something of its fallacies. But I go back now to an earlier occasion when true to his native impulses, he threw into this discussion "for a charm of powerful trouble," personalities most discreditable to this body. I will not stop to repel the imputations which he cast upon myself, but I mention them to remind you of the "sweltered venom sleeping got," which, with other poisoned ingredients, he cast into the caldron of this debate. Of other things, I speak. Standing on this floor, the Senator issued his rescript, requiring submission to the Usurped Power of Kansas, and this was accompanied by a manner all his own, such as befits the tyrannical threat. Very well. Let the Senator try. I tell him now that he cannot enforce any such submission. The Senator, with the slave power at his back, is strong, but he is not strong enough for this purpose. He is bold. He shrinks from nothing. Like Danton, he may cry, "L'audace! L'audace ! toujours L'audace!" but even his audacity cannot compass this work. The Senator copies the British officer who, with boastful swagger, said that with the hilt of his sword, he would cram the "stamps" down the throats of the American people, and he will meet a similar failure. He may convulse this country with a civil feud. Like the ancient madman, he may set fire to this Temple of Constitutional Liberty, grander than the Ephesian dome, but he cannot enforce obedience to that Tyrannical Usurpation.

The Senator dreams that he can subdue the North. He disclaims the open threat, but his conduct still implies it. How little that Senator knows himself or the strength of the cause which he persecutes! He is but a mortal man; against him is an immortal principle. With finite power, he wrestles with the infinite, and he must fall. Against him are stronger battalions than any marshaled by the mortal arm. The inborn, ineradicable, invincible sentiments of the human heart against him is nature in all her subtle forces; against him is God. Let him try to subdue these.

With regret, I come again upon the Senator from South Carolina (Mr. Butler), who, omnipresent in this debate, overflowed with rage at the simple suggestion that Kansas had applied for admission as a State and, with incoherent phrases, discharged the loose expectoration of his speech, now upon her representative, and then upon her people. There was no extravagance of the ancient parliamentary debate, which he did not repeat, nor was there any possible deviation from truth, which he did not make, with so much passion, I am glad to add, as to save him from the suspicion of intentional aberration. But the Senator touches nothing which he does not disfigure with error, sometimes of principle, sometimes of fact. He shows an incapacity of accuracy, whether in stating the Constitution or in stating the law, whether in the details of statistics or the diversions of scholarship. He cannot open his mouth, but out there flies a blunder . . .

But it is against the people of Kansas that the sensibilities of the Senator are particularly aroused. Coming, as he announces, "from a State," aye, sir, from South Carolina, he turns with lordly disgust from this newly-formed community, which he will not recognize even as a "body politic" Pray, sir, by what title does he indulge in this egotism? Has he read the history of "the State" which he represents? He cannot surely have forgotten its shameful imbecility of Slavery, confessed throughout the Revolution, followed by its more shameful assumptions for Slavery since. He cannot have forgotten its wretched persistence in the slave trade as the very apple of its eye and the condition of its participation in the Union. He cannot have forgotten its constitution, which is Republican only in name, confirming power in the hands of the few and founding the qualifications of its legislators on "a settled freehold estate and ten negroes." And yet the Senator, to whom that "State" has in part committed the guardianship of its good name, instead of moving, with backward treading steps, to cover its nakedness, rushes forward in the very ecstasy of madness, to expose it by provoking a comparison with Kansas. South Carolina is old; Kansas is young. South Carolina counts by centuries, where Kansas counts by years. But a beneficent example may be born in a day, and I venture to say that against the two centuries of the older "State," may be already set the two years of trial, evolving corresponding virtue, in the younger community. In the one is the long wail of Slavery; in the other, the hymns of Freedom. And if we glance at special achievements, it will be difficult to find anything in the history of South Carolina that presents so much heroic spirit in a heroic cause appears in that repulse of the Missouri invaders by the beleaguered town of Lawrence, where even the women gave their effective efforts to Freedom. The matrons of Rome who poured their jewels into the treasury for public defence. The wives of Prussia, who, with delicate fingers, clothed their defenders against French invasion, the mothers of our own Revolution, who sent forth their sons, covered with prayers and blessings, to combat for human rights, did nothing of self-sacrifice truer than did these women on this occasion. Were the whole history of South Carolina blotted out of existence, from its very beginning down to the day of the last election of the Senator to his present seat on this floor, civilization might lose. I do not say how little, but surely less than it has already gained by the example of Kansas in its valiant struggle against oppression and in the development of a new science of emigration. Already, in Lawrence alone, there are newspapers and schools, including a High School, and throughout this infant Territory, there is more mature scholarship far, in proportion to its inhabitants, than in all of South Carolina. Ah, sir, I tell the Senator that Kansas welcomed as a free State, will be a "ministering angel" to the Republic when South Carolina, in the cloak of darkness which she hugs, "lies howling."

The Senator from Illinois (Mr. Douglas) naturally joins the Senator from South Carolina in this warfare and gives to it the superior intensity of his nature. He thinks that the National Government has not completely proved its power, as it has never hanged a traitor, but if the occasion requires, he hopes there will be no hesitation, and this threat is directed at Kansas and even at the friends of Kansas throughout the country. Again occurs the parallel with the struggle of our fathers, and I borrow the language of Patrick Henry, when, to the cry from the Senator, of "treason." "Treason," I reply, "if this be treason, make the most of it." Sir, it is easy to call names, but I beg to tell the Senator that if the word "traitor" is in any way applicable to those who refuse submission to a Tyrannical Usurpation, whether in Kansas or elsewhere, then must some new word, of deeper color, be invented, to designate those mad spirits who could endanger and degrade the Republic, while they betray all the cherished sentiments of the fathers and the spirit of the Constitution, in order to give new spread to Slavery. Let the Senator proceed. It will not be the first time in history that a scaffold erected for punishment has become a pedestal of honor. Out of death comes life, and the "traitor" whom he blindly executes will live immortal in the cause.

For Humanity sweeps onward where to-day the martyr stands, On the morrow crouches Judas, with the silver in his hands; When the hooting mob of yesterday in silent awe return, To glean up the scattered ashes into History's golden urn.

Among these hostile Senators, there is yet another, with all the prejudices of the Senator from South Carolina but without his generous impulses, who, on account of his character before the country and the rancor of his opposition, deserves to be named. I mean the Senator from Virginia (Mr. Mason), who, as the author of the Fugitive Slave Bill, has associated himself with a special act of inhumanity and tyranny. Of him, I shall say little, for he has said little in this debate, though within that little was compressed the bitterness of a life absorbed in the support of Slavery. He holds the commission of Virginia, but he does not represent that early Virginia, so dear to our hearts, which gave to us the pen of Jefferson, by which the equality of men was declared, and the sword of Washington, by which Independence was secured; but he represents that other Virginia, from which Washington and Jefferson now avert their faces, where human beings are bred as cattle for the shambles, and where a dungeon rewards the pious matron who teaches little children to relieve their bondage by reading the Book of Life. It is proper that such a Senator, representing such a State, should rail against free Kansas.

Senators such as these are the natural enemies of Kansas, and I introduce them with reluctance, simply that the country may understand the character of the hostility which must be overcome. Arrayed with them, of course, are all who unite, under any pretext or apology, in the propagandism of human Slavery. To such, indeed, the time-honored safeguards of popular rights can be a name only and nothing more. What is trial by jury, habeas corpus, the ballot box, the right of petition, the liberty of Kansas, your liberty, sir, or mine, to one who lends himself, not merely to the support at home, but to the propagandism abroad, of that preposterous wrong, which denies even the right of a man to himself! Such a cause can be maintained only by a practical subversion of all rights. It is, therefore, merely according to reason that its partisans should uphold the Usurpation in Kansas.

To overthrow this Usurpation is now the special, importunate duty of Congress, admitting of no hesitation or postponement. To this end, it must lift itself from the cabals of candidates, the machinations of a party, and the low level of vulgar strife. It must turn from that Slave Oligarchy, which now controls the Republic, and refuse to be its tool. Let its power be stretched forth toward this distant Territory, not to bind, but to unbind; not for the oppression of the weak, but for the subversion of the tyrannical; not for the prop and maintenance of a revolting Usurpation, but for the confirmation of Liberty.

"These are imperial arts and worthy thee!"

Let it now take its stand between the living and dead and cause this plague to be stayed. All this it can do, and if the interests of Slavery did not oppose, all this it would do at once, in reverent regard for justice, law, and order, driving away all the alarms of war nor would it dare to brave the shame and punishment of this great refusal. But the slave power dares anything, and it can be conquered only by the united masses of the people. From Congress to the People, I appeal.

The contest, which, beginning in Kansas, has reached us, will soon be transferred from Congress to a broader stage, where every citizen will be not only a spectator but an actor, and to their judgment, I confidently appeal. To the People, now on the eve of exercising the electoral franchise in choosing a Chief Magistrate of the Republic, I appeal to vindicate the electoral franchise in Kansas. Let the ballot box of the Union, with multitudinous might, protect the ballot box in that Territory. Let the voters everywhere, while rejoicing in their own rights, help to guard the equal rights of distant fellow citizens; that the shrines of popular institutions, now desecrated, may be sanctified anew; that the ballot box, now plundered, may be restored; and that the cry, "I am an American citizen," may not be sent forth in vain against the outrage of every kind. In just regard for free labor in that Territory, which it is sought to blast by unwelcome association with slave labor; in Christian sympathy with the slave, whom it is proposed to task and sell there; in stern condemnation of the crime which has been consummated on that beautiful soil; in rescue of fellow-citizens now subjugated to a Tyrannical Usurpation; in dutiful respect for the early fathers, whose aspirations are now ignobly thwarted; in the name of the Constitution, which has been outraged of the laws trampled down of Justice banished of Humanity degraded of Peace destroyed of Freedom crushed to earth; and, in the name of the Heavenly Father, whose service is perfect Freedom, I make this last appeal."