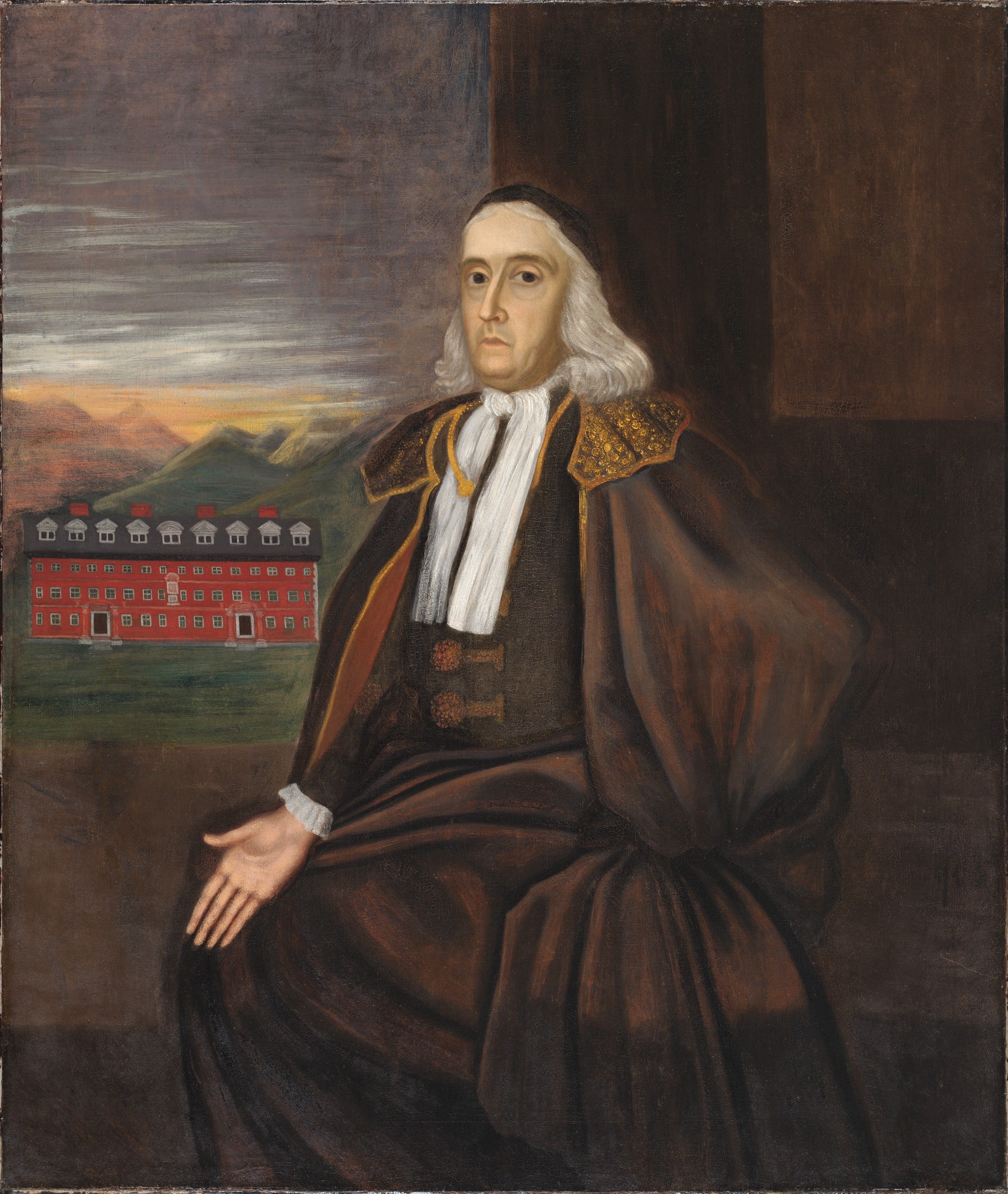

William Stoughton was a prominent figure in Colonial America during the time of the Salem Witch Trials when he served as the Chief Justice of the Court of Oyer and Terminer that was put in place by Governor Phips.

Stoughton made the decision to allow spectral evidence to be used to convict the accused. While there were some, such as Cotton Mather, who believed that spectral evidence was of some use, there were many who were skeptical, which made his decision to allow its use to be admitted into court a controversial one.

Early Life

William Stoughton was born in 1631; however, it is unclear as to where he was born. His family may have migrated to Massachusetts Bay Colony prior to his birth, but there are no records that can confirm it. What is known is that by 1632, the Stoughton's were in the colony, where they were early settlers of Dorchester, Massachusetts.

When Stoughton was a young man, he was accepted into Harvard, where he earned a degree in theology with the intent to become a minister. After graduation, he traveled to England, where he attended Oxford, where he graduated with a Master's degree in theology.

He would remain in England for some time and preach in Sussex. However, after Charles II was restored to the throne, there was a movement against religious dissenters that included Stoughton.

Seeing that it would be tough to gain a position and earn a living in England, he returned to Massachusetts.

Gain of Influence

Upon returning to the colony, Stoughton began preaching at several locations but never took a permanent position because he had gained an interest in politics.

He served on the colony's council of assistants almost every year from 1671 to 1686 and represented the colony in the New England Confederation from 1673 to 1677 and 1680 to 1686.

In the 1684 election, Joseph Dudley, who had been labeled as an enemy of the colony for his moderate position on colonial charter issues, failed to win reelection to the council. Stoughton, who was reelected by a small majority and was a friend and business partner of Dudley, refused to serve in protest.

In 1676, he was chosen, along with Peter Bulkeley, to be an agent representing colonial interests in England. Their instructions were narrowly tailored. They were authorized to acquire land claims from the heirs of Sir Ferdinando Gorges and John Mason, which conflicted with some Massachusetts land claims in present-day Maine.

They were unsuccessful in maintaining broader claims made by Massachusetts against other territories of Maine and the Province of New Hampshire. Their limited authority upset the Lords of Trade, who sought to have the colonial laws modified to conform to their policies. The mission of Stoughton and Bulkley did little more than antagonize colonial officials in London because of their hardline stance.

For many years, Stoughton and Joseph Dudley were friends, as well as political and business partners. The two worked closely together politically and engaged in land development together. In the 1680s, Stoughton acquired significant amounts of land from the Nipmuc tribe in what is now Worcester County in partnership with Dudley.

The partnership included a venture that established Oxford as a place to settle refugee Huguenots.

Dudley and Stoughton used their political positions to ensure that the titles to lands they were interested in were judicially cleared, a practice that also benefited their friends, relatives, and other business partners.

Concerning this practice, Crown agent Edward Randolph wrote that it was "impossible to bring titles of land to trial before them where his Majesties' rights are concerned, the Judges also being parties."

This was particularly obvious when Stoughton and Dudley were part of a venture to acquire 1 million acres of land in the Merrimack River valley. Dudley's council, on which Stoughton and other investors sat, formally cleared that land's title in May 1686.

When Dudley was commissioned in 1686 to head the Dominion of New England temporarily, Stoughton was appointed to his council, and he was then elected by the council as the deputy president. During the administration of Sir Edmund Andros, he served as a magistrate and on the council. As a magistrate, he was particularly harsh on the town leaders of Ipswich, who had organized tax protests against the dominion government based on the claim that dominion rule without representation violated the Rights of Englishmen.

When Andros was arrested in April 1689 in a bloodless uprising inspired by the 1688 Glorious Revolution in England, Stoughton was one of the signatories to the declaration of the revolt's ringleaders.

Despite this statement of support for the popular cause, he was sufficiently unpopular due to his association with Andros that he was denied elective offices.

He appealed to the politically powerful Mather family, with whom he still had positive relations. In 1692, when Increase Mather and Sir William Phips arrived from England carrying the charter for the new Province of Massachusetts Bay and a royal commission for Phips as governor, they also brought one for Stoughton as lieutenant governor.

Salem Witch Trials

Rumors of witchcraft had been gaining momentum during the year 1692, and the village of Salem seemed to be at the center. People had already been put into jail on accusations of participating in witchcraft, and Governor Phips was forced to deal with the issue immediately when he returned from England.

Phips then appointed Stoughton to head a special tribunal to handle the accusations of witchcraft that had been placed on many people. He would also be appointed as Chief Justice.

During the Salem Witch Trials, Stoughton acted as both chief judge and prosecutor. He was particularly harsh on some of the defendants, sending the jury deliberating in the case of Rebecca Nurse back to reconsider its not guilty verdict; after doing so, she was convicted.

Many convictions were made because Stoughton permitted the use of spectral evidence, which was a divisive issue at the time as many judges expressed reservations about its use.

Stoughton, however, was convinced of its acceptability and may have influenced other judges to this view. The special court stopped sitting in September 1692.

In November and December 1692, Governor Phips oversaw a reorganization of the colony's courts to bring them into conformance with English practice. The new courts, with Stoughton still sitting as chief justice, began to handle the witchcraft cases in 1693 but were under specific instructions from Phips to disregard spectral evidence.

As a result, a significant number of cases were dismissed due to a lack of evidence, and Phips vacated the few convictions that were made. On 3 January 1693, Stoughton ordered the execution of all suspected witches who had been exempted from their pregnancy. Phips denied enforcement of the order.

This turn of events angered Stoughton, and he briefly left the bench in protest.

It has been argued that Stoughton's acceptance of spectral evidence was based partly on a need he saw to reassert Puritan authority in the province.

Unlike his colleague Samuel Sewall, who later expressed regret for his actions on the bench in the trials, Stoughton never admitted that his actions and beliefs with respect to spectral evidence and the trials were in error

Conclusion

William Stoughton died in 1701 while serving as Governor

He is often viewed as one of the "bad guys" of the Salem Witch Trials due to his insistence on the use of spectral evidence during the trials. His treatment of the accused is another reason for the negative view of him.

He, like John Hathorne, never apologized for his actions during the trials, and there is no evidence of any remorse, which suggests he believed that he was justified in what he did to those who were accused and executed.

It is clear that Stoughton's actions during the trials absolutely led to the death of over 20 people who were either executed or died in jail.

<- Return to the List of People Involved in the Salem Witch Trials