The Battle of Appomattox Court House began the end of the war and is generally recognized as the end of the war, although it is not. There were many dangerous Confederate armies in the South still roaming, but after Lee's surrender, the dominos would fall quickly.

General Ulysses S. Grant's terms are often recognized as generous, and it would resonate with Robert E. Lee for the rest of his life. He would be a defender of Grant for the rest of his life despite living in the South.

This also marked the end of the illustrious career of Robert E. Lee. He had served faithfully in the Mexican War and was known for his ability prior to secession. He served bravely for the South, and his greatness became how long his army lasted against a superior foe. If not for Grant, then it is possible the country would have never united, and Lee could have turned the political opinion around on Lincoln.

The Battle

Robert E. Lee took the starving remains of his still-proud army west, hoping to feed them from supplies that he believed would arrive at Amelia Court House; when they didn't, he was forced to feed them from the countryside, all the while warding off Union attacks there and at Tabernacle Church.

Philip Sheridan sets his cavalry across the Danville Railroad at Petersburg, cutting off an escape route and forcing Lee to move towards Farmville and skirmishes at Amelia Springs and Paine's Cross Roads on April 5.

An accidental dividing of his army is an advantage for the Federals at Saylers Creek; Lee loses more than 8,000 men - one-third of his army -to capture. The forced delay also benefitted the Federals in another way: they captured Lee's supply train.

On the 7th, Abraham Lincoln received a message sent to Ulysses S. Grant from Philip Sheridan:

"If the thing is pressed, I think Lee might surrender." Abraham Lincoln wired to General Grant: "Let the thing be pressed."

Grant learned of several trainloads of supplies and forage at Appomattox, and Sheridan made his move to capture them. He then sat down and composed a letter to Lee:

The result of the last week must convince you of the hopelessness of further resistance on the part of the Army of Northern Virginia in this struggle. I feel that it is so, and regard it as my duty to shift from myself the responsibility of any further effusion of blood by asking of you the surrender of that portion of the Confederate States army known as the Army of Northern Virginia.

Robert E. Lee replied, and it was not what Grant had hoped for:

GENERAL: I have received your note of this day. Though not entertaining the opinion you express on the hopelessness of further resistance on the part of the Army of Northern Virginia, I reciprocate your desire to avoid useless effusion of blood, and therefore, before considering your proposition, ask the terms you will offer on condition of its surrender.

Grant replied to General Lee and wrote out the terms that were based on what he believed President Abraham Lincoln would want:

Your note of last evening in reply to mine of the same date, asking the condition on which I will accept the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia, is just received. In reply, I would say that peace being my great desire, there is but one condition I would insist upon, namely, that the men and officers who surrendered shall be disqualified from taking up arms again against the Government of the United States until properly exchanged. I will meet you or will designate officers to meet any officers you may name for the same purpose, at any point agreeable to you, for the purpose of arranging definitely the terms upon which the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia will be received.

Shortly after responding to Lee, General Grant came down with a terrible headache that could not be cured. It was during this painful time that Lee requested.

GENERAL: I received, at a late hour, your note of today. In mine of yesterday, I did not intend to propose the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia but to ask the terms of your proposition. To be frank, I do not think the emergency has arisen to call for the surrender of this army, but as the restoration of peace should be the sole object of all, I desired to know whether your proposals would lead to that end. I cannot, therefore, meet you with a view to the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia, but as far as your proposal may affect the Confederate States forces under my command and tend to the restoration of peace, I should be pleased to meet you at ten A.M. to-morrow on the old stage-road to Richmond, between the picket-lines of the two armies.

When Grant received the letter, he knew that the Confederate Surrender was not quite at hand and that Lee still intended to continue the war.

The End Of The Army of Northern Virginia

At dawn on April 9, John B. Gordon's Second Corps attacked Sheridan's cavalry and quickly forced back the first line, while Confederate cavalry under Fitzhugh Lee moved around the Union flank.

The second line, held by Ranald S. Mackenzie and George Crook, fell back. Gordon's troops charged through the Union lines and took the ridge, but as they reached the crest, they saw the entire Union XXIV Corps in line of battle with the V Corps to their right.

Immediately, the battle fizzled out; Fitz Lee's cavalry withdrew and rode off towards Lynchburg. Ord's troops began advancing against Gordon's corps, while the Union II Corps began moving against General James Longstreet's corps to the northeast.

Colonel Charles Venable of Lee's staff rode in at this time and asked for an assessment, and Gordon gave him a reply he knew Lee didn't want to hear:

Tell General Lee I have fought my corps to a frazzle, and I fear I can do nothing unless I am heavily supported by Longstreet's corps.

When Robert E. Lee learned of the words of the Colonel, he knew his war had come to an end. He then said his famous words:

Then there is nothing left me to do but to go and see General Grant, and I would rather die a thousand deaths."

He then reluctantly sat down and wrote a letter to General Ulysses S. Grant and requested a meeting:

GENERAL: I received your note of this morning on the picket line, whither I had come to meet you and ascertain definitely what terms were embraced in your proposal of yesterday with reference to the surrender of this army. I now ask for an interview, in accordance with the offer contained in your letter of yesterday, for that purpose.

General Grant, still suffering from a terrible headache, received the letter. After he finished reading, it is said that his headache left him, and began preparing for a meeting with Lee.

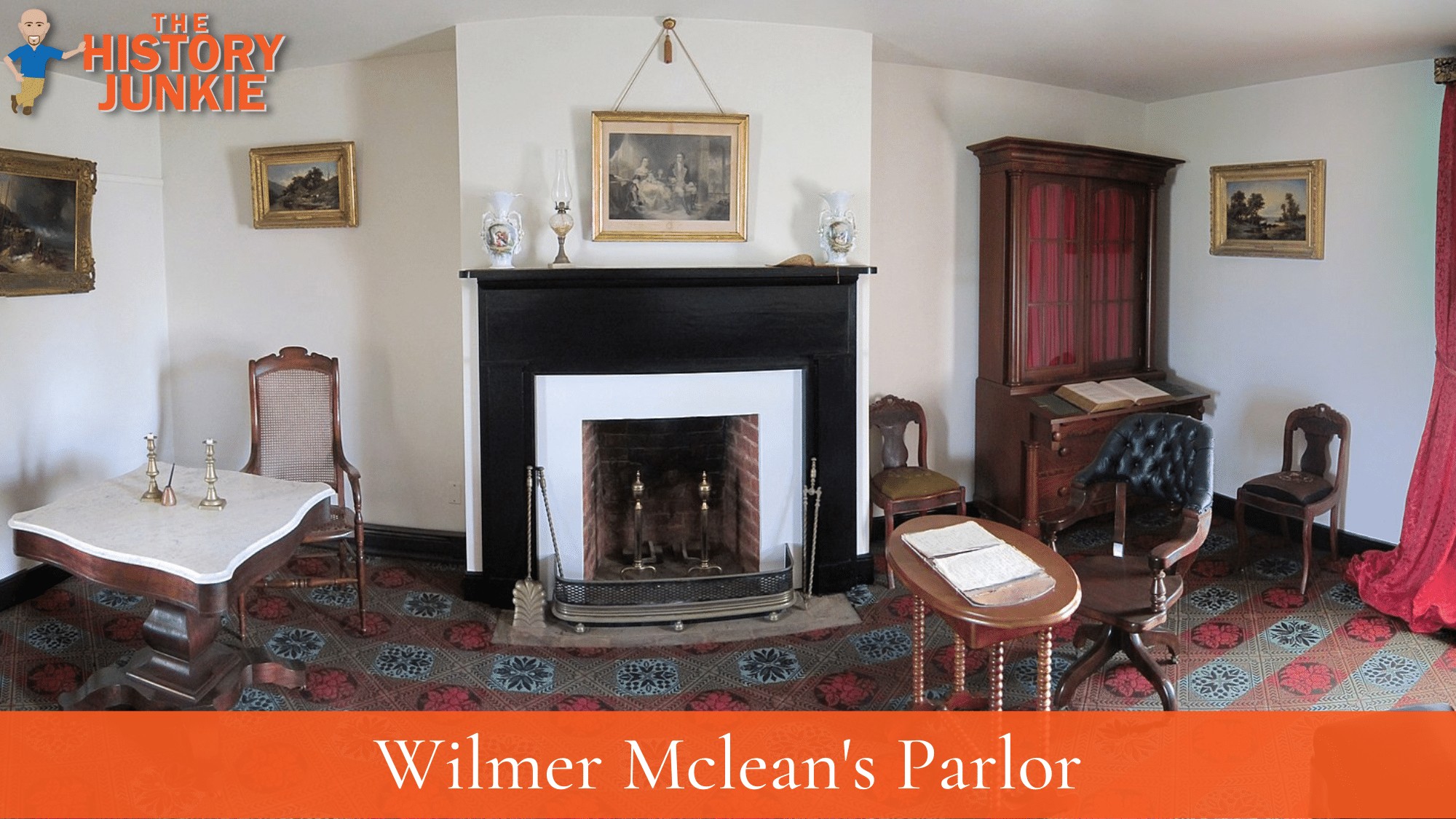

Wilmer McLean's House

Upon selecting a location for the meeting, there was only one location that seemed suitable.

In one of the more ironic stories of the Civil War, the home of Wilmer McLean was chosen. McLean had a connection to the First Battle of Bull Run.

Union Army artillery fired at McLean's house, which was being used as a headquarters for Confederate Brigadier General P. G. T. Beauregard, and a cannonball dropped through the kitchen fireplace.

Beauregard wrote after the battle,

A comical effect of this artillery fight was the destruction of the dinner of myself and staff by a Federal shell that fell into the fire-place of my headquarters at the McLean House.

Throughout the next couple of years of the war, McLean grew tired of the constant battles being fought near him. Although he had been in the Virginia militia prior to the war, he was too old to resume activities and made a living as a sugar broker, which became difficult with both armies nearby.

In 1863, he decided to move to Appomattox County, and it would be his home that was chosen for the final negotiations between Grant and Lee at the Battle of Appomattox Court House. It is believed he said the following:

The war began in my front yard and ended in my front parlor.

The Meeting

At the Battle of Appomattox Court House, Lee arrived dressed in his finest uniform, a sash around his waist and a saber hanging at his side. He stood in McLean's parlor for thirty minutes when Grant finally arrived, wearing his uniform casually with mud-spattered boots and a private's overcoat with a general's shoulder straps hastily sewn on.

A pleasant conversation began about times in the Mexican War until Lee brought up the subject of the meeting.

Grant replied that Lee's army

should lay down their arms, not to take them up again during the continuance of the war unless duly and properly exchanged.

Lee suggested that the terms be made in writing:

GEN: In accordance with the substance of my letter to you of the 8th inst., I propose to receive the surrender of the Army of N. Va. on the following terms, to wit: Rolls of all the officers and men to be made in duplicate. One copy is to be given to an officer designated by me, the other to be retained by such officer or officers as you may designate. The officers were to give their individual paroles not to take up arms against the Government of the United States until properly exchanged, and each company or regimental commander sign a like parole for the men of their commands. The arms, artillery, and public property to be parked and stacked and turned over to the officer appointed by me to receive them. This will not embrace the side-arms of the officers, nor their private horses or baggage. This done, each officer and man will be allowed to return to their homes, not to be disturbed by United States authority so long as they observe their paroles and the laws in force where they may reside.

Lee read the document and said the terms would have a happy effect on the men but saw something not mentioned that caused some distress. There were soldiers, cavalrymen, and artillerists who owned their own horses, and he wanted to know if these animals could be retained.

Grant stated that according to the terms, they would not, to which Lee reluctantly agreed. But after some thought - and with the realization that the spring planting season was about to start - Grant issued orders that all Confederates who claimed to own a horse or mule would be allowed to take them home to work their farms.

He wrote the following:

GENERAL: I received your letter of this date containing the terms of the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia as proposed by you. As they are substantially the same as those expressed in your letter of the 8th inst., they are accepted. I will proceed to designate the proper officers to carry the stipulations into effect.

All that was left for Lee to do was to return to his lines, where he gave a few tear-filled remarks to his men. Grant, on the other hand, sent a simple message to Washington:

General Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia this afternoon on terms proposed by myself. The accompanying additional correspondence will show the conditions fully.

The celebrations were stopped by Grant - who did not want to gloat in the enemy's downfall - but there was wild euphoria in Washington where, despite heavy rain, some three thousand citizens came out to the parade, play music, and celebrate what they thought was the end of the war.

One of the parades ended at the White House, of which Lincoln came out to applause. Expecting a speech, the president asked for something else:

Fellow citizens: I am very greatly rejoiced to find that an occasion has occurred so pleasurable that the people cannot restrain themselves. I suppose that arrangements are being made for some sort of a formal demonstration this, or perhaps, tomorrow night. If there should be such a demonstration, I, of course, will be called upon to respond, and I shall have nothing to say if you dribble it all out of me before. I see you have a band of music with you. I propose closing up this interview by the band performing a particular tune which I will name. Before this is done, however, I wish to mention one or two little circumstances connected with it. I have always thought `Dixie’ one of the best tunes I have ever heard. Our adversaries, over the way, attempted to appropriate it, but I insisted yesterday that we fairly captured it. I presented the question to the Attorney General, and he gave it as his legal opinion that it is our lawful prize. I now request the band to favor me with its performance.’

But as of April 10, 1865, there were still several major rebel armies in the field that had to be dealt with. However, with Lee's surrender at the Battle of Appomattox Court House and Sherman's continued advance, the dominos would fall soon.

Robert E. Lee's Final Words To His Men

On April 10, Lee gave his farewell address to his army, which is often called General Order No. 9:

After four years of arduous service marked by unsurpassed courage and fortitude, the Army of Northern Virginia has been compelled to yield to overwhelming numbers and resources.

I need not tell the survivors of so many hard-fought battles, who have remained steadfast to the last, that I have consented to the result from no distrust of them.

But feeling that valor and devotion could accomplish nothing that could compensate for the loss that must have attended the continuance of the contest; I have determined to avoid the useless sacrifice of those whose past services have endeared them to their countrymen.

By the terms of the agreement, officers and men can return to their homes and remain until exchanged. You will take with you the satisfaction that proceeds from the consciousness of duty faithfully performed, and I earnestly pray that a merciful God will extend to you his blessing and protection.

With an unceasing admiration of your constancy and devotion to your Country and a grateful remembrance of your kind and generous consideration for me, I bid you an affectionate farewell.

The Final Moments

The same day, a six-man commission gathered to discuss a formal ceremony of surrender, even though no Confederate officer wished to go through with such an event.

Brigadier General Joshua L. Chamberlain was the Union officer selected to lead the ceremony, and later, he would reflect on what he witnessed on April 12, 1865, and write a moving tribute:

The momentous meaning of this occasion impressed me deeply. I resolved to mark it by some token of recognition, which could be no other than a salute of arms. Well aware of the responsibility assumed and of the criticisms that would follow, as the sequel proved, nothing of that kind could move me in the least. The act could be defended, if needful, by the suggestion that such a salute was not to the cause for which the flag of the Confederacy stood but to its going down before the flag of the Union. My main reason, however, was one for which I sought no authority nor asked forgiveness. Before us in proud humiliation stood the embodiment of manhood: men whom neither toils and sufferings, nor the fact of death, nor disaster, nor hopelessness could bend from their resolve; standing before us now, thin, worn, and famished, but erect, and with eyes looking level into ours, waking memories that bound us together as no other bond;- was not such manhood to be welcomed back into a Union so tested and assured?

Instructions had been given, and when the head of each division column came opposite our group, our bugle sounded the signal, and instantly, our whole line from right to left, regiment by regiment in succession, gives the soldier's salutation from the "order arms" to the old "carry"- the marching salute. Gordon at the head of the column, riding with heavy spirit and downcast face, catches the sound of shifting arms, looks up, and, taking the meaning, wheels superbly, making with himself and his horse one uplifted figure, with profound salutation as he drops the point of his sword to the boot toe; then facing to his own command, gives the word for his successive brigades to pass us with the same position of the manual,- honor answering honor. On our part, not a sound of trumpet more, nor roll of drum; not a cheer, nor word nor whisper of vain-glorying, nor motion of man standing again at the order, but an awed stillness rather, and breath-holding, as if it were the passing of the dead!

27,805 Confederate soldiers passed by that day, stacked their arms, and went home.