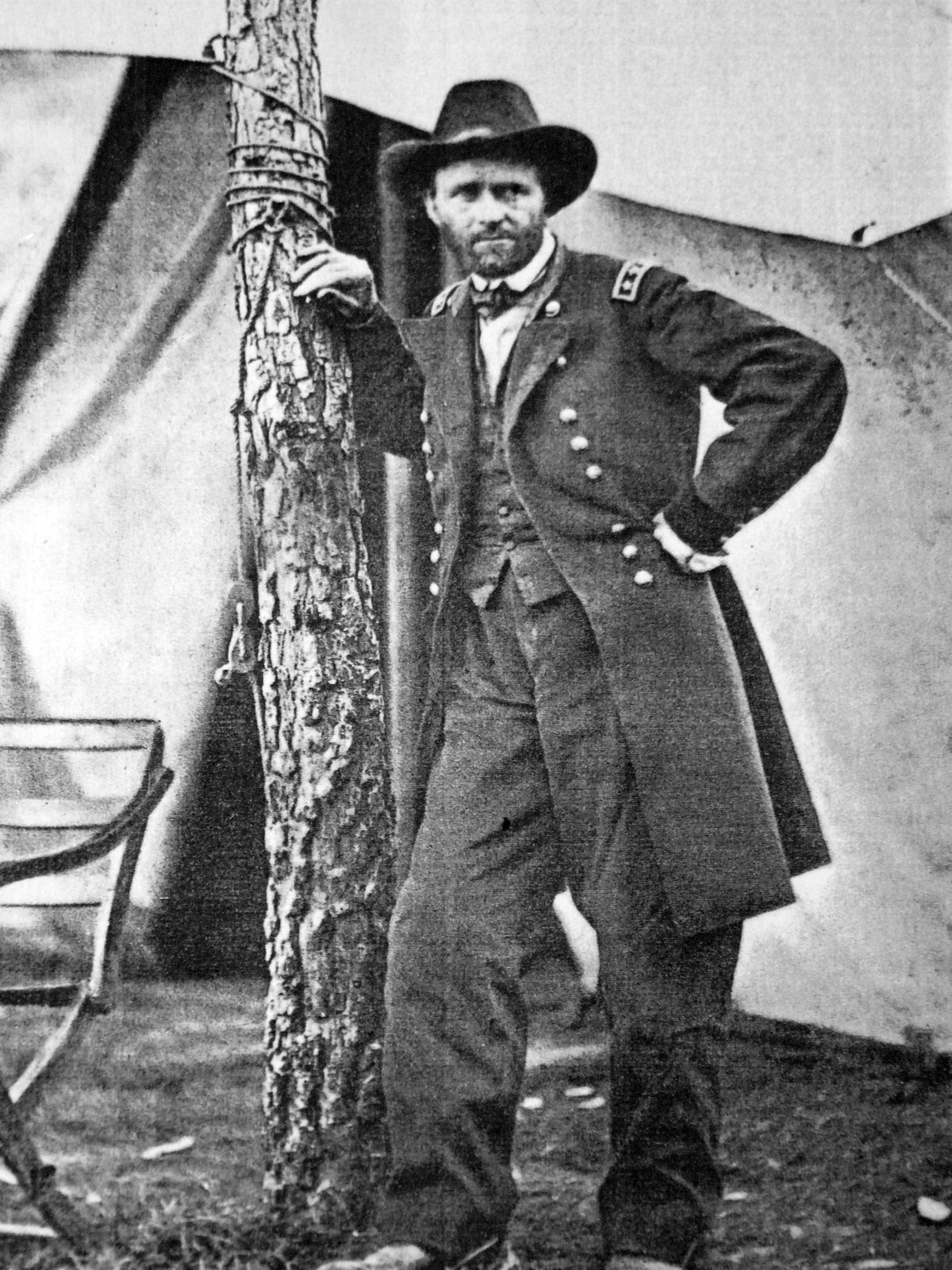

The Vicksburg Campaign was a series of major and minor battles during the American Civil War led by Major General Ulysses S. Grant, culminating in the battle of Vicksburg that ended on July 4, 1863. The surrender of Vicksburg opened up the Mississippi River as a vital waterway and split the Confederacy in two.

Often cited as the turning point of the Civil War is the Battle of Gettysburg. While it was important, it was the victory at Vicksburg that strategically was the beginning of the end of the Confederacy.

Jump to:

Prelude

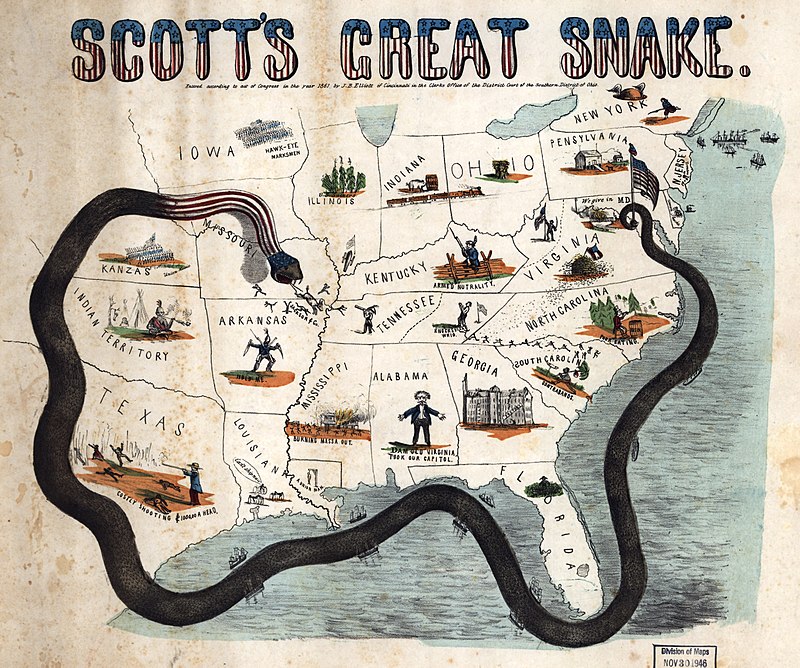

At the time of the Civil War, the Mississippi River was the single most important economic feature of the continent; the very lifeblood of America. Upon the secession of the southern states, Confederate forces closed the river to navigation, which threatened to strangle northern commercial interests.

President Abraham Lincoln told his civil and military leaders, "See what a lot of land these fellows hold, of which Vicksburg is the key! The war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket... We can take all the northern ports of the Confederacy, and they can defy us from Vicksburg." Lincoln assured his listeners that "I am acquainted with that region and know what I am talking about, and as valuable as New Orleans will be to us, Vicksburg will be more so."

It was imperative for the administration in Washington to regain control of the lower Mississippi River, thereby opening that important avenue of commerce-enabling the rich agricultural produce of the Northwest to reach world markets. It would also split the South in two, sever a vital Confederate supply line, achieve a major objective of Winfield Scott's Anaconda Plan, and effectively seal the doom of Richmond.

In the spring of 1863, Major General Ulysses S. Grant launched his Union Army of Tennessee on a campaign to pocket Vicksburg and provide President Lincoln with the key to victory.

The Canals

In the summer of 1862, as the ships of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron under Flag Officer David Glasgow Farragut bombarded the Vicksburg River defenses, a 3,000-man infantry brigade commanded by Brig. Gen. Thomas Williams began work on this canal.

The purpose of the canal was to create a channel for navigation that would bypass the Confederate batteries at Vicksburg. The scouring effect of the Mississippi River's current would keep the canal open. It was believed by some that the man-made channel would possibly even catch enough of the current's force to cause the river to change course, leaving the city high and dry and making Vicksburg worthless militarily without firing a shot.

Work on the canal commenced on June 27, 1862, as soldiers from Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont, Wisconsin, and Michigan began felling trees and turning dirt. Disease, however, began to spread like wildfire through the ranks, and dysentery, diarrhea, malaria, and various fevers took a heavy toll on human life. Men also fell victim by the score to heat exhaustion and sunstroke.

"The labor of making this cut is far greater than estimated by anybody," confessed Williams, who complained bitterly, "The health of the troops has been much impaired by the absence of proper shelter. The quarters on board the transports are hot and crowded, and those onshore are no protection against rain."

To augment his fast-dwindling workforce, Williams reported that "Between 1,100 and 1,200 blacks, gathered from neighboring plantations by armed parties, are now engaged in the work of excavating, cutting down trees, and grubbing up roots."

In spite of the heat, the canal was excavated to a depth of thirteen feet and a width of eighteen feet, impractical for navigation. By July 24, work on the canal stopped, and Williams' weary soldiers accompanied the West Gulf Blockading Squadron as Farragut withdrew to safer water. Williams was killed two weeks later in the Battle of Baton Rouge. In January 1863, work on the canal was resumed by troops under the command of Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant.

Although he placed little confidence in the success of this project, Grant approved of the idea as it would keep his soldiers in good physical condition for the spring campaign and, more important, keep the spirit of the offensive alive. President Lincoln, however, was enthralled with the scheme and, almost on a daily basis, walked across the lawn of the White House to the War Department to inquire of Grant, "How's work on the canal coming along?" In spite of Grant's somewhat optimistic replies, William Sherman noted with candor, "The canal doesn't amount to much."

As the soldiers and blacks that had been pressed into service dug lower, there was a sudden rise in the river, which broke through the dam at the head of the canal and flooded the area. The canal began to fill up with backwater and sediment.

In a desperate effort to rescue the project, two huge steam-driven dipper dredges, "Hercules" and "Sampson," were put to work clearing the channel. The dredges, however, were exposed to Confederate artillery fire from the bluffs at Vicksburg and driven away. By late March, Grant had decided to make a bold change in operations and work on the canal was abandoned.

Lake Providence Canal

As Union soldiers labored on the canal across De Soto Point, opposite Vicksburg, Grant's engineers investigated alternate water routes to reach Vicksburg. One such route led through a 200-mile connecting chain of waterways from Lake Providence to the mouth of Red River, thence up the Mississippi River another 150 miles to Vicksburg. The route could also be used to send reinforcements to assist Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks in his operations against Port Hudson.

The route was examined by Lt. Col. William L. Duff of Grant's staff and declared practicable, provided a short channel of five-foot depth was cut from the levee to Lake Providence. A working party from Col. George W. Deitzler's brigade began excavating the ditch in early February 1863.

Once the ditch was completed, the levee would be blown, permitting floodwater from the Mississippi, then fifteen feet higher than the level of the lake, to rush in and provide water of sufficient depth for vessels to cross Lake Providence to Bayou Baxter and on into Bayou Macon from which there would be clear passage over other streams to the Red River.

In early March, Grant personally examined the route and reported that "there was scarcely a chance of this ever becoming a practicable route for moving troops through an enemy's country." Despite his outlook, work on the canal continued, and on March 17, the levee was cut. By the 23rd, the water levels of the Mississippi and Lake Providence were nearly equal, permitting vessels to be taken in. By the end of March, however, Grant had determined to move his army south overland from Milliken's Bend, and the Lake Providence Expedition was abandoned.

Federal efforts at Lake Providence had the unforeseen result of protecting the right flank of Grant's column as it marched south from Milliken's Bend because the flooded interior waterways of Louisiana provided an extensive water barrier against Confederate raids. The flooded waterways also helped to shield Union enclaves at Lake Providence, Milliken's Bend, and Young's Point.

Grant's march

The spring of 1863 signaled the beginning of the final and, for the Union, the successful phase of the Vicksburg Campaign as General Grant launched his Army of Tennessee on a march down the west side of the Mississippi River from Milliken's Bend to Hard Times, Louisiana.

Leaving their encampments on March 29, Union soldiers took up the line of march and slogged southward over a muddy road. Building bridges and corduroying roads, Grant's column pushed first to New Carthage, then to Hard Times, where the infantrymen rendezvoused with the Union fleet.

On April 16, while Grant's army marched south through Louisiana, part of the Union fleet commanded by Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter prepared to run by the Vicksburg batteries. At 9:15 p.m., lines were cast off, and the vessels moved away from their anchorage with engines muffled, and all lights extinguished to conceal the movement.

As the boats rounded De Soto Point, above Vicksburg, they were spotted by Confederate lookouts who spread the alarm. Bales of cotton soaked in turpentine and barrels of tar that lined the shore were set on fire by the Confederates to illuminate the river.

Although each vessel was hit repeatedly, Porter's fleet successfully fought its way past the Confederate batteries with the loss of only one transport and headed toward a rendezvous with Grant on the Louisiana shore south of Vicksburg.

Bombardment of Grand Gulf

It was Grant's intention to force a crossing of the river at Grand Gulf and move on to "Fortress Vicksburg" from the south. For five hours on April 29, the Union fleet bombarded the Grand Gulf defenses in an attempt to silence the Confederate guns and prepare the way for a landing. The fleet, however, sustained heavy damage and failed to achieve its objective. Admiral Porter declared, "Grand Gulf is the strongest place on the Mississippi."

Not wishing to send his transports loaded with troops to attempt a landing in the face of enemy fire, Grant disembarked his command and continued the march south along the levee.

Crossing at Bruinsburg

Undaunted by his failure at Grand Gulf, Grant moved farther south in search of a more favorable crossing point. Looking now to cross his army at Rodney, Grant was informed that there was a good road ascending the bluffs east of Bruinsburg. Seizing the opportunity, the Union commander hurled his army across the mighty river and onto Mississippi soil at Bruinsburg on April 30 May 1, 1863. In the early morning hours of April 30, infantrymen of the 24th and 46th Indiana Regiments stepped ashore on Mississippi soil at Bruinsburg. The invasion had begun.

The landing was made unopposed, and as the men came ashore, a band aboard the ironclad gunboat U.S.S. Benton struck up "The Red, White, and Blue." The Hoosiers were quickly followed by the remainder of the XIII Union Army Corps and portions of the XVII Corps, 17,000 men.

Elements of the Union Army pushed inland and took possession of the bluffs, thereby securing the landing area. By late afternoon of April 30, 17,000 soldiers were ashore, and the march inland began. Having pushed inland from the landing area at Bruinsburg, Union soldiers rested and ate their crackers in the shade of the trees on Windsor Plantation.

Late that afternoon, the decision was made to push on that night by a forced march in hopes of surprising the Confederates and preventing them from destroying the bridges over Bayou Pierre. The Union columns resumed the advance at 5:30 p.m. Instead of taking the Bruinsburg Road, which was the direct road from the landing area to Port Gibson, Grant's columns swung onto the Rodney Road, passed Bethel Church, and marched through the night.

Battle of Port Gibson

Shortly after midnight, the crash of musketry shattered the stillness as the Federals stumbled upon Confederate outposts near the A. K. Shaifer house. Union troops immediately deployed for battle, and artillery, which soon arrived, roared into action. A spirited skirmish ensued, which lasted until 3 a.m.

The Confederates held their ground. For the next several hours, an uneasy calm settled over the woods and scattered fields as soldiers of both armies rested on their arms. Throughout the night, the Federals gathered their forces in hand, and both sides prepared for the battle that they knew would come with the rising sun.

At dawn, Union troops began to move in force along the Rodney Road toward Magnolia Church. One division was sent along a connecting plantation road toward the Bruinsburg Road and the Confederate right flank. With skirmishers well in advance, the Federals began a slow and deliberate advance around 5:30 a.m. The Confederates contested the thrust, and the battle began in earnest.

Most of the Union forces moved along the Rodney Road toward Magnolia Church and the Confederate line held by Brigadier General Martin E. Green's Brigade. Heavily outnumbered and hard-pressed, the Confederates gave way shortly after 10:00 a.m. The men in butternut and gray fell back a mile and a half. Here, the soldiers of Brigadier General William E. Baldwin's and Colonel Francis M. Cockrell's brigades, recent arrivals on the field, established a new line between White and Irwin branches of Willow Creek. Full of fight, these men re-established the Confederate left flank.

The morning hours witnessed Green's Brigade driven from its position by the principal Federal attack. Brigadier General Edward D. Tracy's Alabama Brigade astride the Bruinsburg Road also experienced hard fighting. Although Tracy was killed early in action, his brigade managed to hold its tenuous line.

It was clear, however, that unless the Confederates received heavy reinforcements, they would lose the day. Brigadier General John S. Bowen, Confederate commander on the field, wired his superiors: "We have been engaged in a furious battle ever since daylight; losses very heavy. The men act nobly, but the odds are overpowering." Early afternoon found the Alabamans slowly giving ground. Green's weary soldiers, having been reformed, arrived to bolster the line on the Bruinsburg Road.

Even so, late in the afternoon, the Federals advanced all along the line in superior numbers. As Union pressure built, Cockrell's Missourians unleashed a vicious counterattack near Rodney Road, which began to roll up the blue line. The 6th Missouri was also counterattacked, hitting the Federals near the Bruinsburg Road. All this was to no avail, for the odds against them were too great. The Confederates were checked and driven back. The day was lost. At 5:30 p.m., battle-weary Confederates began to retire from the hard-fought field.

The battle of Port Gibson cost Grant 131 killed, 719 wounded, and 25 missing out of 23,000 men engaged. This victory not only secured his position on Mississippi soil but enabled him to launch his campaign deeper into the interior of the state. Union victory at Port Gibson forced the Confederate evacuation of Grand Gulf and would ultimately result in the fall of Vicksburg.

The Confederates suffered 60 killed, 340 wounded, and 387 missing out of 8,000 men engaged. In addition, 4 guns of the Botetourt (Virginia) Artillery were lost. The action at Port Gibson underscored the Confederate inability to defend the line of the Mississippi River and to respond to amphibious operations.

Pushing inland

To support the army's push inland, Grant established a base on the Mississippi River at Grand Gulf. (Contrary to popular belief, the Union army relied heavily on supplies from the Grand Gulf to sustain its movements in Mississippi. Only after reaching Vicksburg and re-establishing contact with the fleet on the Yazoo River did Grant abandon the supply line from Grand Gulf.) Instead of marching directly on Vicksburg from the south, Grant marched his army in a northeasterly direction with his left flank protected by the Big Black River.

It was Grant's intention to strike the Southern Railroad of Mississippi somewhere between Vicksburg and Jackson. Destruction of the railroad would cut Pemberton's supply and communications line and isolate Vicksburg. As the Federal force moved inland, McClernand's Corps was on the left, William T. Sherman's in the center, and James B. McPherson's on the right.

Battle of Raymond

On the morning of May 12, 1863, Major General James B. McPherson's XVII Corps was marching along the road from Utica toward Raymond. Shortly before 10:00 a.m., the Union skirmish line swept over a ridge and moved cautiously through open fields into the valley of Fourteenmile Creek, southwest of Raymond. Suddenly, a deadly volley ripped into their ranks from the woods, which lined the almost-dry stream. During the course of the battle, McPherson massed 22 guns astride the road to support his infantry.

Confederate artillery also roared into action, announcing the presence of Brigadier General John Gregg's battle-hardened brigade. The ever-combative Gregg decided to strike with his 3,000-man brigade, turn the Federal right flank, and capture the entire force. Faulty intelligence led Gregg to believe that he faced only a small Union force when, in reality, McPherson's 10,000-man corps was on the road before him.

Thick clouds of smoke and dust obscured the field, and neither commander accurately assessed the size of the force in his front. Gregg enjoyed initial success, but as successive Confederate regiments attacked across the creek to the left, resistance stiffened, and it became clear that a much larger Federal force was on the field. By early afternoon, the Confederate attack was checked, and Union forces counterattacked.

Union brigades continued to arrive on the field and deploy in line of battle on either side of the Utica road. In piecemeal fashion, McPherson's men pushed forward at 1:30 p.m. and drove the Confederates back across Fourteenmile Creek. The fighting that ensued was of the most confusing nature, for neither commander knew where their units were or what they were doing.

Union strength of numbers, however, prevailed. The Confederate right flank along the Utica road broke under renewed pressure, and Gregg had no alternative but to retire from the field. His regiments retreated through Raymond and out the Jackson road, bivouacking for the night near Snake Creek. There was no Federal pursuit as McPherson's troops bedded down for the night in and around the town.

The fight at Raymond cost Gregg 73 killed, 252 wounded, and 190 missings, most of whom were from the 3rd Tennessee and the 7th Texas. McPherson's losses totaled 446, of whom 68 were killed, 341 wounded, and 37 missing.

Battle of Jackson

The engagement at Raymond led Grant to change the direction of his army's march and move on to Jackson, the state capital. It was Grant's intention to destroy Jackson as a rail and communications center and scatter any Confederate reinforcements that might be on the way to Vicksburg. McPherson's Corps moved north through Raymond to Clinton on May 13, while Major General William T. Sherman pushed northeast through Raymond to Mississippi Springs. To cover the march on Jackson, Major General John A. McClernand's Corps was placed in a defensive posture on a line from Raymond to Clinton.

Late in the afternoon of May 13, as the Federals were poised to strike at Jackson, a train arrived in the capital city carrying Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston. Ordered to Jackson by President Jefferson Davis, Johnston was to salvage the rapidly deteriorating situation in Mississippi. Establishing his headquarters at the Bowman House, General Johnston was appraised of troop strength and the condition of the fortifications around Jackson. He immediately wired authorities in Richmond, "I am too late." Instead of fighting for Jackson, Johnston ordered the city evacuated. Gregg was ordered to fight a delaying action to cover the evacuation.

Heavy rain fell during the night, which turned the roads into mud. Advancing slowly through torrential rain, the corps of Sherman and McPherson converged on Jackson by mid-morning of May 14. Around 9 o'clock, the lead elements of McPherson's corps were fired upon by Confederate artillery posted on the O. P. Wright farm. Quickly deploying his men into the line of battle, the Union Corps commander prepared to attack.

Suddenly, the rain fell in sheets and threatened to ruin the ammunition of his men by soaking the powder in their cartridge boxes. The attack was postponed until the rain stopped around 11:00 a.m. The Federals then advanced with bayonets fixed and banners unfurled. Clashing with the Confederates in a bitter hand-to-hand struggle, McPherson's men forced the Southerners back into the fortifications of Jackson.

Sherman's corps meanwhile reached Lynch Creek southwest of Jackson at 11 o'clock and was immediately fired upon by Confederate artillery posted in the open fields north of the stream. Union cannons were hurried into position and, in short, order drove the Confederates back into the city's defenses.

The stream was bank full, and Sherman's men crossed on a narrow wooden bridge. Reforming their lines, the Federals advanced at 2:00 p.m. until they were stopped by canister fire. Not wishing to expose his men to the deadly fire, Sherman sent one regiment to the right (east) in search of a weak spot in the defense line. These men reached the works and found them deserted. Only a handful of state troops and civilian volunteers were left to man the guns in Sherman's front.

At 2:00 p.m., Gregg was notified that the army's supply train had left Jackson and decided to withdraw his command. The Confederates moved quickly to evacuate the city and were well out the Canton Road to the north when Union troops entered Jackson around 3 o'clock. The "Stars and Stripes" were unfurled atop the capitol by McPherson's men, symbolic of Union victory.

Confederate casualties in the battle of Jackson were not accurately reported but estimated at 845 killed, wounded, and missing. In addition, 17 artillery pieces were taken by the Federals. Union casualties totaled 300 men, of whom 42 were killed, 251 wounded, and 7 missing.

Not wishing to waste combat troops on occupation, Grant ordered Jackson to neutralize militarily. The torch was applied to machine shops and factories, telegraph lines were cut, and railroad tracks were destroyed. With Jackson neutralized and Johnston's force scattered to the winds, Grant turned his army west with confidence toward his objective, Vicksburg.

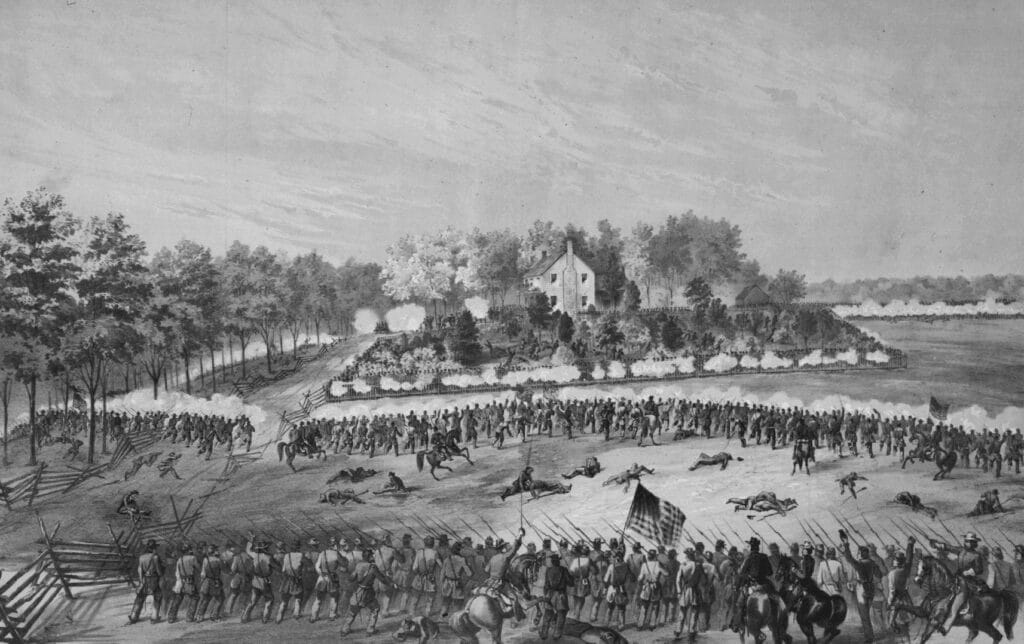

Battle of Champion Hill

Early on the morning of May 16, 1863, General Grant received news that Confederate forces were at Edwards Station, preparing to march east. He ordered his columns forward. Moving westward from Bolton and Raymond, blue-clad soldiers slogged over rapidly drying roads in three parallel columns. At about 7 a.m., the southernmost column made contact with Confederate pickets near the Davis Plantation, and shots rang out.

Once contact had been made, Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton, the Confederate commander, quickly deployed his three divisions. The Confederate battle line, three miles in length, ran from southwest to northeast along the military crest of a ridge overlooking Jackson Creek. The crest of Champion Hill, on the left of the line, was picketed as a security measure. Pemberton's position was suited for defense and was especially formidable against attacks via the Middle and Raymond roads.

The Confederate commander, however, was unaware that a strong Union force was pushing down the Jackson Road toward his unprotected left flank. If unchecked, this Union force would capture Edwards and cut the Confederates off from their base of operation, Vicksburg.

Shortly after 9 a.m., a courier brought a warning of the Federal advance along the Jackson Road. Confederate troops were shifted to the left to cover Champion Hill and protect the vital crossroads. As the Confederates hastened into position on the crest of Champion Hill, Federal soldiers near the Champion house swung from column into a double line of battle. Union artillery was wheeled into position and unlimbered. The bloodshed began in earnest when the guns roared into action.

Grant arrived near the Champion house around 10 o'clock. After surveying the situation, he ordered the attack. Two Union divisions, 10,000 men in battle array, moved forward in magnificent style with flags flying. The long blue lines extended westward beyond the Confederate flank. To meet this threat, Confederate troops shifted farther to the west, creating a gap between the forces defending the Crossroads and those defending the Raymond Road.

By 11:30, the Northerners closed in on the Confederate main line of resistance. With a cheer, they stormed the position. The fighting was intense as the battle raged on Champion Hill. The lines swayed back and forth as charge and countercharge were made. But the strength of numbers prevailed, and the blue tide swept over the crest of Champion Hill shortly after 1 p.m.

The Confederates fell back in disorder to the Jackson Road, followed closely by the hard-driving Federals. The powerful Union drive captured the Crossroads and, on the right, severed the Jackson Road escape route. Confronted by disaster, Pemberton ordered his two remaining divisions to counterattack. Leaving one brigade to guard the Raymond Road, the Confederates marched from their right along the Ratliff Road toward the Crossroads.

With characteristic abandon, the 4,500 soldiers of Brigadier General John S. Bowen's division attacked. With fury and determination, they hit the Federals near the Crossroads. At the point of the bayonet, they drove the Federals back three-quarters of a mile and regained control of Champion Hill. The attack, however, was made with insufficient numbers and faltered short of the Champion house.

Grant exerted himself to prevent a breakthrough and ordered up fresh troops to drive back the Confederates. In addition, the Federals along the Middle and Raymond roads began to drive hard. All morning, they had operated under instructions to "move cautiously" but now were thrown forward. In a matter of moments, Confederate resistance was shattered, and Pemberton ordered his army from the field.

With only one avenue of escape open to them, the Confederates fled toward the Raymond Road crossing of Bakers Creek. Brigadier General Lloyd Tilghman's Brigade, acting as the rear guard for the Confederate army, was ordered to hold its ground at all costs. In so doing, General Tilghman was killed. His brigade, along with the rest of Major General William W. Loring's division, was cut off from Edwards and eventually made its way to Jackson by a circuitous route.

The victorious Federals gained control of the Bakers Creek bridge late in the afternoon and, at about 8 p.m., entered Edwards. This smashing victory cost Grant 410 killed, 1,844 wounded, and 187 missing out of 32,000 men. But victory at Champion Hill guaranteed the success of his campaign.

May 16, 1863, was a disastrous day for Pemberton. His army lost 381 killed, 1,018 wounded, and 2,441 missing out of the 23,000 men he carried into battle. In addition, 27 artillery pieces were lost.

Battle of Big Black River

Pemberton ordered Bowen's division and a fresh brigade commanded by Brigadier General John Vaughn to hold the bridges across Big Black River long enough for Loring to cross. Unbeknownst to Pemberton, however, Loring was not marching toward the river. Instead, Federal troops appeared early in the morning and prepared to storm the defenses. McClernand's XIII Corps quickly deployed astride the road, and artillery opened on the Confederate fortifications with solid shots and shells.

The Confederate line was naturally strong and formed an arc with its left flank resting on Big Black River and the right flank on Gin Lake. A bayou of waist-deep water fronted a portion of the line, and 18 cannons were placed to sweep the flat open ground to the east. As both sides prepared for battle, Union troops took advantage of terrain features, and Brigadier General Mike Lawler, on the Federal right, deployed his men in a meander scar not far from the Confederate line of defense.

Believing that his men could cover the intervening ground quickly and with little loss, Lawler boldly ordered his troops to fix bayonets and charge. With a mighty cheer, the Federals swept across the open ground, through the bayou, and over the parapets.

Overwhelmed by the charge, Confederate soldiers threw down their rifle muskets and ran toward the bridges across the river. In the panic and confusion of defeat, many Confederate soldiers attempted to swim across the river and drowned. Luckily, Pemberton's chief engineer, Major Sam Lockett, set the bridges on fire, effectively cutting off pursuit by the victorious Union army. Badly shaken, the Confederates staggered back into the Vicksburg defenses and prepared to resist the Union onslaught.

Confederate losses at the Big Black River Bridge were not accurately reported, but 1,751 men, 18 cannons, and 5 battle flags were captured by the Federals. Union casualties totaled only 279 men, of whom 39 were killed, 237 wounded, and 3 missing. Grant's forces bridged the river at three locations and, flushed with victory, pushed hard toward Vicksburg on May 18.

Vicksburg

First assault

Anxious for a quick victory, Grant made a hasty reconnaissance of the Vicksburg defenses and ordered an assault. Of his three corps, however, only one was in a proper position to make the attack-Sherman's corps astride the Graveyard Road northeast of Vicksburg. Early in the morning, Union artillery opened fire and bombarded the Confederate works with solid shots and shells.

With lines neatly dressed and their battle flags blowing in the breeze above them, Sherman's troops surged across the fields at 2:00 p.m. and through the abatis (obstructions of felled trees) toward Stockade Redan.

Although the men of the 1st Battalion, 13th United States Infantry, planted their colors on the exterior slope of Stockade Redan (a powerful Confederate fort that guarded the road), the attack was repulsed with Federal losses numbering 1,000 men.

Storming the stronghold

Undaunted by his failure on the 19th and realizing that he had been too hasty, Grant made a more thorough reconnaissance and then ordered another assault. Early on the morning of May 22, Union artillery opened fire and, for four hours, bombarded the city's defenses.

At 10:00, the guns fell silent, and Union infantry was thrown forward along a three-mile front. Sherman attacked once again down the Graveyard Road, McPherson in the center along the Jackson Road, and McClernand on the south along the Baldwin Ferry Road and astride the Southern Railroad of Mississippi. Flags of all three corps were planted at different points along the exterior slope of Confederate fortifications.

McClernand's men even made a short-lived penetration at Railroad Redoubt. But the Federals were again driven back with a loss in excess of 3,000 men.

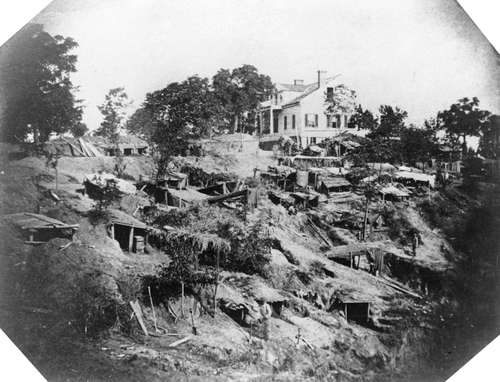

The siege

Following the failure of the May 22 assault, Grant realized that Vicksburg could not be taken by storm and decided to lay siege to the city. Slowly, his army established a line of work around the beleaguered city and cut Vicksburg off from supply and communications with the outside world.

Commencing on May 26, Union forces constructed thirteen approaches along their front aimed at different points along the Confederate defense line. The object was to dig up to the Confederate works, then tunnel underneath them, plant charges of black powder, and destroy the fortifications. Union troops would then surge through the breach and gain entrance to Vicksburg.

Throughout the month of June, Union troops advanced their approaches slowly toward the Confederate defenses. Protected by the fire of sharpshooters and artillery, Grant's fatigue parties neared their objectives by late June.

Along Jackson Road, a mine was detonated beneath the Third Louisiana Redan on June 25, and Federal soldiers swarmed into the crater, attempting to exploit the breach in the city's defenses. The struggle raged for 26 hours, during which time clubbed muskets and bayonets were freely used as the Confederates fought with grim determination to deny their enemy access to Vicksburg. The troops in blue were finally driven back to the point of the bayonet, and the breach sealed. On July 1, a second mine was detonated but not followed by an infantry assault.

June was a weary month for the gallant defenders of Vicksburg, as they suffered under the constant bombardment of enemy guns, as well as from meager rations and exposure to the elements. Reduced in number by sickness and battle casualties, the garrison of Vicksburg was spread dangerously thin. Soldiers and citizens alike began to despair that relief would ever come.

At Jackson and Canton, General Johnston gathered a relief force that took up the line of march toward Vicksburg on July 1. By then, it was too late, as the sands of time had expired for the fortress city on the Mississippi River.

Surrender

On the hot afternoon of July 3, 1863, a cavalcade of horsemen in gray rode out from the city along the Jackson Road. Soon, white flags appeared on the city's defenses as General Pemberton rode beyond the works to meet with his adversary, Grant. The two generals dismounted between the lines, not far from the Third Louisiana Redan, and sat in the shade of a stunted oak tree to discuss surrender terms. Unable to reach an agreement, the two men returned to their respective headquarters.

Grant told Pemberton he would have his final terms by 10 p.m. True to his word. Grant sent his final amended terms to Pemberton that night. Instead of unconditional surrender of the city and garrison, Grant offered parole to the valiant defenders of Vicksburg. Pemberton and his generals agreed that these were the best terms that could be had, and in the quiet of his headquarters on Crawford Street, the decision was made to surrender the city.

At 10 a.m., on July 4, white flags were again displayed from the Confederate works, and the brave men in gray marched out of their entrenchments, stacked their arms, removed their accouterments, and furled their flags, at which time the victorious Union army marched in and took possession the city.

When informed of the city's surrender, President Lincoln exclaimed, "The Father of Waters again goes unvexed to the sea."

The Battle of Vicksburg was over.

The fall of Vicksburg, coupled with the defeat of Confederate General Robert E. Lee in the battle of Gettysburg, fought on July 1–3, marked the turning point of the Civil War.