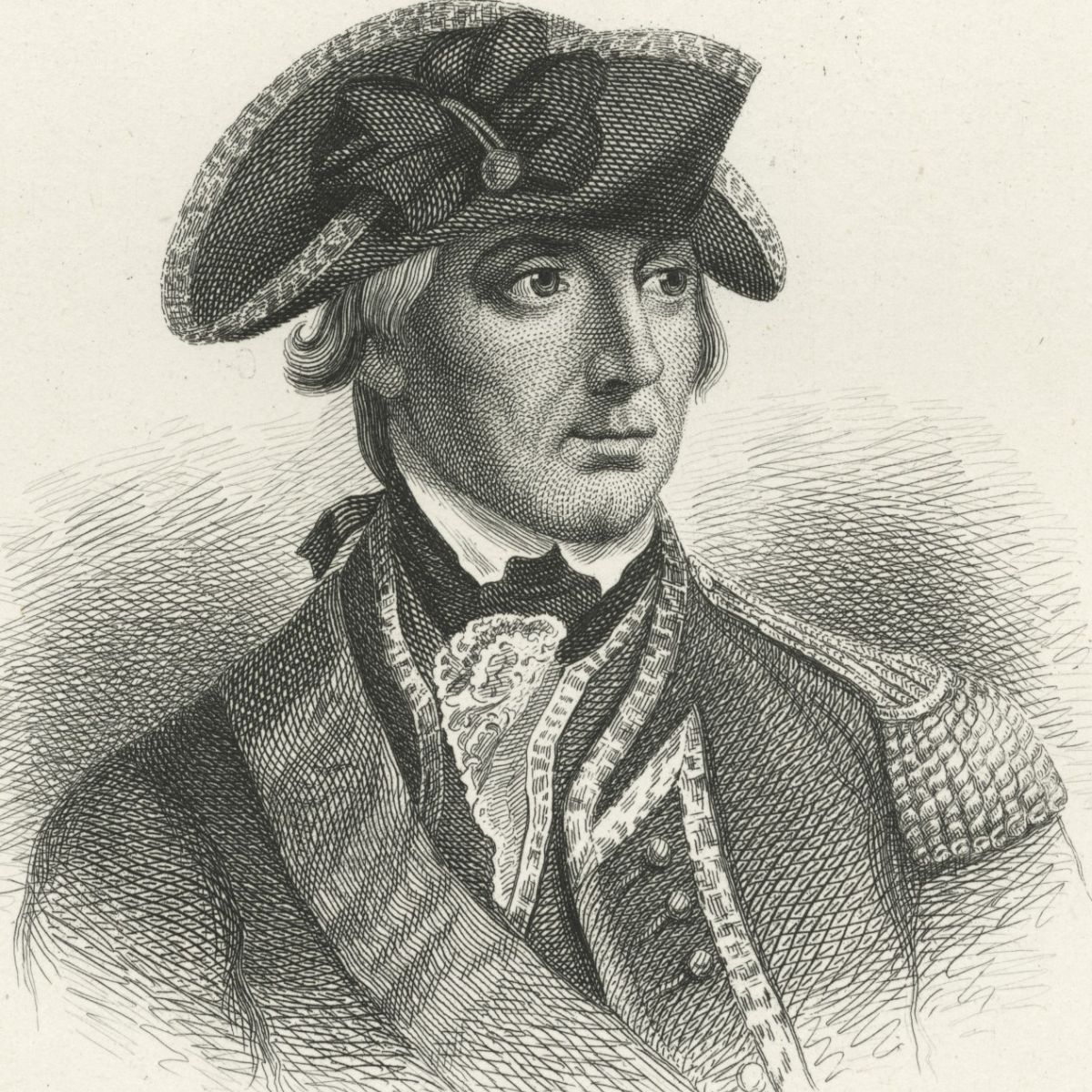

General William Howe was a British army officer who rose to become Commander-in-Chief of British forces during the American Revolutionary War. Howe was one of three brothers who enjoyed distinguished military careers.

Having joined the army in 1746, Howe saw extensive service in the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years' War. General William Howe became known for his role in the capture of Quebec in 1759 when he led a British force to capture the cliffs at Anse-au-Foulon, allowing James Wolfe to land his army and engage the French.

Howe also participated in the campaigns to take Louisbourg, Belle Île, and Havana.

General William Howe was sent to North America in March 1775, arriving in May after the American Revolutionary War broke out. After leading British troops to a costly victory in the Battle of Bunker Hill, Howe took command of all British forces in America from Thomas Gage in September of that year. Howe's record in North America was marked by the successful capture of both New York City and Philadelphia.

However, poor British campaign planning for 1777 contributed to the failure of John Burgoyne's Saratoga campaign, which played a major role in the entry of France into the war. Howe's role in developing those plans and the degree to which he was responsible for British failures that year (despite his personal success at Philadelphia) have been a subject of contemporary and historical debate.

He resigned his post as Commander-in-Chief, North America, in 1778 and returned to England, where he was at times active in the defense of the British Isles. He served for many years in Parliament and was knighted after his successes in 1776.

He inherited the Viscountcy of Howe upon the death of his brother Richard in 1799. He married but had no children, and the viscountcy was extinguished with his death in 1814.

Jump to:

Early Life

General William Howe was born in England, the third and youngest son of Emanuel Howe, 2nd Viscount Howe and Charlotte, the daughter of Sophia von Kielmansegg, Countess of Leinster and Darlington, an acknowledged illegitimate daughter of King George I. His mother was a regular in the courts of George II and George III.

This connection with the crown may have improved the careers of all three sons, but all would prove to be capable officers. His father was a politician who served as Governor of Barbados, where he died in 1735.

William's eldest brother was General George Howe, who was killed just before the 1758 Battle of Carillon at Fort Ticonderoga. His other brother was Admiral Richard Howe, who rose to become one of Britain's leading naval commanders.

He entered the army when he was 17 by buying a cornet's commission in the Duke of Cumberland's Dragoons in 1746. He then served for two years in Flanders during the War of the Austrian Succession. After the war, he was transferred to the 20th Regiment of Foot, where he became a friend of James Wolfe.

Seven Years' War

During the Seven Years' War, Howe's service first brought him to America and did much to raise his reputation. He joined the newly formed 58th Regiment of Foot in February 1757 and was promoted to lieutenant colonel in December of that year. He commanded the regiment at the Siege of Louisbourg in 1758, leading an amphibious landing under heavy enemy fire. This action won the attackers a flanking position and earned Howe commendations from Wolfe.

Howe commanded a light infantry battalion under General Wolfe during the 1759 Siege of Quebec. He was in the Battle of Beaufort and was chosen by Wolfe to lead the ascent from the Saint Lawrence River up to the Plains of Abraham that led to the British victory in the Battle of the Plains of Abraham on 13 September 1759.

After spending the winter in the defense of Quebec City, his regiment fought in the April 1760 Battle of Sainte-Foy and led a brigade in the capture of Montreal under Jeffery Amherst before returning to England. Howe led a brigade in the 1761 Capture of Belle Île, off the French coast, and turned down the opportunity to become military governor after its capture so that he might continue in active service. He served as adjutant-general of the force that captured Havana in 1762, playing a part in a skirmish at Guanabacoa.

In 1758, Howe was elected a Member of Parliament for Nottingham, succeeding to the seat vacated by his brother George's death. His election was assisted by the influence of his mother, who campaigned for her son while he was away at war and may very well have been undertaken because service in Parliament was seen as a common way to improve one's prospects for advancement in the military.

In 1764, he was promoted to colonel of the 46th Regiment of Foot, and in 1768, he was appointed the lieutenant governor of the Isle of Wight. As tensions rose between Britain and the colonies in the 1770s, Howe continued to rise through the ranks and came to be widely regarded as one of the best officers in the army. He was promoted to major-general in 1772 and, in 1774, introduced new training drills for light infantry companies.

In Parliament, he was generally sympathetic to the American colonies. He publicly opposed the collection of legislation intended to punish the Thirteen Colonies, known as the Intolerable Acts, and in 1774, assured his constituents that he would resist active duty against the Americans and asserted that the entire British army could not conquer America.

He also let government ministers know privately that he was ready to serve in America as second in command to Thomas Gage, who he knew was unpopular in government circles. In early 1775, when King George called on him to serve, he accepted, claiming publicly that if he did not, he would suffer "the odious name of backwardness to serve my country in distress."

He sailed for America in March 1775, accompanied by Major Generals Henry Clinton and John Burgoyne. In May 1775, his colonelcy was transferred to the 23rd Fusiliers.

American Revolutionary War

Howe arrived at Boston on 25 May, having learned en route that the American Revolutionary War had broken out with the Battles of Lexington and Concord in April. He led a force of 4,000 troops sent to reinforce the 5,000 troops under General Thomas Gage that was besieged in the city after those battles.

Gage, along with Howe and Generals Clinton and Burgoyne, discussed plans to break the siege. They formulated a plan to seize high ground around Boston and then attack the besieging militia forces and planned its execution for 18 June.

However, the colonists learned of the plan and fortified the heights of Breed's Hill on the Charlestown peninsula on the night of 16–17 June, forcing the British leadership to review their strategy.

Battle of Bunker Hill

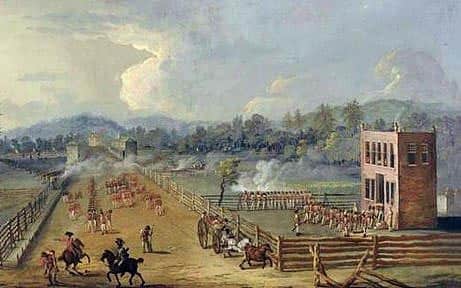

In a war council held early on 17 June, the generals developed a plan calling for a direct assault on the colonial fortification, and Gage gave Howe command of the operation.

Despite a sense of urgency, the attack, now known as the Battle of Bunker Hill, did not begin until that afternoon. With Howe personally leading the right wing of the attack, the first two assaults were firmly repulsed by the colonial defenders.

Howe's third assault gained the objective, but the cost of the day's battle was appallingly heavy. The British casualties, more than 1,000 killed or wounded, were the highest of any engagement in the war.

Howe described it as a "success ... too dearly bought." Although Howe exhibited courage on the battlefield, his tactics and overwhelming confidence were criticized. One subordinate wrote that Howe's "absurd and destructive confidence" played a role in the number of casualties incurred.

Although General William Howe was not injured in the battle, it had a pronounced effect on his spirit. According to British historian George Otto Trevelyan, the battle "exercised a permanent and most potent influence,", especially on Howe's behavior, and that Howe's military skills then "were apt to fail him at the very moment when they were especially wanted."

Despite an outward appearance of confidence and popularity with his troops, the "genial six-footer with a face some people described as 'coarse'" privately often exhibited a lack of self-confidence and, in later campaigns, became somewhat dependent on his older brother Richard for advice and approval.

On 11 October 1775, General Gage sailed for England, and Howe took over as Commander-in-Chief of the British Army in America. British military planners in London had, with the outbreak of hostilities, begun planning a massive reinforcement of the troops in North America.

Their plans, made with recommendations from Howe, called for the abandonment of Boston and the establishment of bases in New York and Newport, Rhode Island is, trying to isolate the rebellion to New England. When orders arrived in November to execute these plans, Howe opted to stay in Boston for the winter and begin the campaign in 1776.

As a result, the rest of the Siege of Boston was largely a stalemate. Howe never attempted a major engagement with the Continental Army, which had come under the command of Major General George Washington. He did, however, spend a fair amount of time at the gambling tables and allegedly established a relationship with Elizabeth Lloyd Loring, the wife of Loyalist Joshua Loring, Jr. Loring apparently acquiesced to this arrangement and was rewarded by Howe with the position of the commissary of prisoners.

Contemporaries and historians have criticized Howe for both his gambling and the amount of time he supposedly spent with Mrs. Loring, with some going so far as to level accusations that this behavior interfered with his military activities.

In January 1776, Howe's role as commander-in-chief was cemented with a promotion to full general in North America.

The siege was broken in March 1776 when Continental Army Colonel Henry Knox brought heavy artillery from Fort Ticonderoga to Boston during the winter, and General Washington used them to fortify Dorchester Heights, overlooking Boston and its harbor.

Howe at first planned an assault on this position, but a snowstorm interfered, and he eventually decided to withdraw from Boston. On March 17, British troops and Loyalists evacuated the city and sailed for Halifax, Nova Scotia.

New York Campaign

Howe and his troops began to arrive outside New York Harbor and made an uncontested landing on Staten Island in early July. Howe's orders were fairly clear that he should avoid conflict before the arrival of reinforcements, then wait until those reinforcements arrived in mid-August, along with the naval commander, his brother Richard.

After moving most of his army to southwestern Long Island without opposition, he attacked the American positions on August 27. In a well-executed maneuver, a large column led by Howe and Clinton passed around the American left flank, routing the Americans from their forward positions into the entrenchments on Brooklyn Heights.

Despite the urging of Clinton and others, Howe decided against an immediate assault on these fortifications, claiming "the Troops had for that day done handsomely enough." This decision would ultimately cost him George Washington. Washington and his army would escape at night when a thick fog covered New York.

That would be the closest Howe would ever get to capture Washington.

Howe and his brother Richard had, as part of their instructions, been assigned roles as peace commissioners with limited authority to treat the rebels. After Long Island, they pursued an attempt at reconciliation, sending the captured General John Sullivan to Philadelphia with a proposal for a peace conference.

The meeting that resulted, conducted by Admiral Howe, was unsuccessful. The Howes had been given limited powers, as had the Congressional representatives, and the latter was insistent that the British recognize the recently declared colonial independence. This was not within Howe's powers, so the conference failed, and Howe then continued the campaign.

New York Occupation

General William Howe first landed troops on Manhattan on September 15 and occupied New York City (which then occupied only Lower Manhattan), although his advance northward on Manhattan was checked the next day at Harlem Heights. He then paused, spending nearly one-month consolidating control of New York City and awaiting reinforcements.

During this time, he ordered Nathan Hale's execution for espionage and had to deal with the effects of a major fire in the city. He then attempted a landing on the mainland at Throgs Neck, intending to flank Washington's position at Harlem Heights.

However, the narrow causeway between the beach and the mainland was well-defended, and he ended up withdrawing the troops. He then made a successful landing of troops at Pell's Point in Westchester County; Washington managed to avoid being flanked, retreating to White Plains.

Howe successfully forced Washington out of the New York area in the October 28 Battle of White Plains and then turned his attention to consolidating the British hold on Manhattan. In November, he attacked the remaining Continental Army stronghold in the Battle of Fort Washington, taking several thousand prisoners.

Washington then retreated across New Jersey, followed by Howe's advance forces under Charles Cornwallis. At this point, Howe prepared troops under the command of General Clinton for embarkation to occupy Newport, the other major goal of his plan.

Clinton proposed that these troops instead be landed in New Jersey, either opposite Staten Island or on the Delaware River, trapping Washington or even capturing the seat of the Continental Congress, Philadelphia. Howe rejected these proposals, dispatching Clinton and General Hugh, Earl Percy, two vocal critics of his leadership, to take Newport.

In early December, Howe came to Trenton, New Jersey, to arrange to dispose of his troops for the winter. Washington had retreated all the way across the Delaware River, and Howe returned to New York, believing the campaign to be ended for the season.

When Washington attacked the Hessian quarters at Trenton on 26 December 1776, Howe sent Cornwallis to reform the army in New Jersey and chase after Washington. Cornwallis was frustrated in this, with Washington gaining a second victory at Trenton and a third at Princeton.

Howe recalled the army to positions closer to New York for the winter.

Philadelphia Campaign

On 30 November 1776, as General George Washington was retreating across New Jersey, General William Howe had written to Lord Germain with plans for the 1777 campaign season.

He proposed to send a 10,000-man force up the Hudson River to capture Albany, New York, with an expedition sent south from the Province of Quebec. He again wrote to Germain on December 20, 1776, with more elaborate proposals for 1777.

These again included operations to gain control of the Hudson River and included expanded operations from the base at Newport and an expedition to take Philadelphia.

The latter Howe saw as attractive since Washington was then just north of the city: Howe wrote that he was "persuaded the Principal Army should act offensively, where the enemy's chief strength lies." Germain acknowledged that this plan was particularly "well digested," but it called for more men than Germain was prepared to provide.

After the setbacks in New Jersey, Howe, in mid-January 1777, proposed operations against Philadelphia that included an overland expedition and a sea-based attack, thinking this might lead to a decisive victory over the Continental Army.

When the campaign season opened in May 1777, General Washington moved most of his army from its winter quarters in Morristown, New Jersey, to a strongly fortified position in the Watchung Mountains. In June 1777, Howe began a series of odd moves in New Jersey, apparently trying to draw Washington and his army out of that position onto terrain more favorable for a general engagement.

His motives for this are uncertain; Washington had intelligence that Howe had moved without taking the heavy river-crossing equipment and was apparently not fooled at all.

When Washington failed to take the bait, Howe withdrew the army to Perth Amboy. Washington moved down to a more exposed position, assuming Howe was going to embark his army on ships. Howe then launched a lightning strike designed to cut Washington's retreat off.

This attempt was foiled by the Battle of Short Hills, which gave Washington time to retreat to a more secure position. Howe then did, in fact, embark his army and sailed south with his brother's fleet.

Howe maintained effective secrecy surrounding the fleet's destination: not only did Washington not know where it was going, but neither did many British officers.

Capture of Philadelphia

Howe's campaign for Philadelphia began with an amphibious landing at Head of Elk, Maryland Colony, southwest of the city in late August. Although Howe would have preferred to make a landing on the Delaware River below Philadelphia, reports of well-prepared defenses dissuaded him, and the fleet spent almost an entire extra month at sea to reach Head of Elk.

On September 11, 1777, Howe's army met Washington's near Chadds Ford along the Brandywine Creek in the Battle of Brandywine.

Howe established his headquarters at the Gilpin Homestead, where it stayed until the morning of September 16. In a reprise of earlier battles, Howe once again flanked the Continental Army position and forced Washington to retreat after inflicting heavy casualties.

After two weeks of maneuvering, Howe triumphantly entered the city on September 26. The reception the British received was not quite what they had expected, however. They had been led to believe that "Friends thicker than Woods" would greet them upon their arrival; they instead were greeted by women, children, and many deserted houses.

Despite Howe's best attempts to minimize the plundering by his army, this activity by the army had a significant negative effect on popular support.

One week after Howe entered Philadelphia, on October 4, Washington made a dawn attack on the British garrison at Germantown. He very nearly won the battle before being repulsed by late-arriving reinforcements sent from the city. This forced Howe to withdraw his troops a little closer to the city, where they also needed to help clear the American Delaware River defenses, which were preventing the navy from resupplying the army.

It was late November before this task was accomplished, which included a poorly executed attack on Fort Mercer by a division of Hessians.

Saratoga Campaign

Parallel with Howe's campaign, General Burgoyne led his expedition south from Montreal to capture Albany. Burgoyne's advance was stopped in the Battles of Saratoga in September and October, and he surrendered his army on October 17. Burgoyne's surrender, coupled with Howe's near defeat at Germantown, dramatically altered the strategic balance of the conflict.

Support for the Continental Congress, suffering from Howe's successful occupation of Philadelphia, was strengthened, and the victory encouraged France to enter the war against Britain. Burgoyne's loss also further weakened the British government of Lord North.

Burgoyne made his advance under the assumption that he would be met in Albany by Howe or troops sent by Howe. Burgoyne was apparently not aware that Howe's plans evolved the way they did. Although Lord Germain knew what Howe's plans were, whether he communicated them to Burgoyne is unclear.

Some sources claim he did, while others state that Burgoyne was not notified of the changes until the campaign was well underway. Whether Germain, Howe, and Burgoyne had the same expectations about the degree to which Howe was supposed to support the invasion from Quebec is also unclear.

Howe himself wrote to Burgoyne on July 17 that he intended to stay close to Washington: "My intention is for Pennsylvania, where I expect to meet Washington, but if he goes to the northward contrary to my expectations, and you can keep him at bay, be assured I shall soon be after him to relieve you."

This suggested that Howe would follow Washington if he went north to assist in the defense of the Hudson.

Howe, however, sailed from New York on July 23. On August 30, shortly after his arrival at Head of Elk, Howe wrote to Germain that he would be unable to assist Burgoyne, citing a lack of Loyalist support in the Philadelphia area. A small force sent north from New York by General Clinton in early October was also unable to assist Burgoyne.

Resignation

In October 1777, Howe sent his letter of resignation to London, complaining that he had been inadequately supported in that year's campaigns. He was finally notified on April 1778 that his resignation was accepted.

A grand party, known as the "Mischianza," was thrown for the departing general on 18 May. Organized by his aides John André and Oliver De Lancey Jr., the party featured a grand parade, fireworks, and dancing until dawn.

Washington, aware that the British were planning to evacuate Philadelphia, sent the Marquis de Lafayette out with a small force on the night of the party to determine British movements. This movement was noticed by alert British troops, and Howe ordered a column out to entrap the marquis. In the Battle of Barren Hill, Lafayette escaped the trap with minimal casualties.

On 24 May, the day Howe sailed for England, General Clinton took over as commander-in-chief of British armies in America and made preparations for an overland march to New York. Howe arrived back in England on July 1, where he and his brother faced censure for their actions in North America.

It is likely that the resignation of both William and his brother Richard was due to their desire to hurry home to defend their conduct during the campaign.

In 1779, Howe and his brother demanded a parliamentary inquiry into their actions. The inquiry that followed was unable to confirm any charges of impropriety or mismanagement leveled against either of them.

Because of the inconclusive nature of the inquiry, attacks continued to be made against Howe in pamphlets and the press, and in 1780, he published a response to accusations leveled by Loyalist Joseph Galloway.

Later Life

In 1780, General William Howe lost in his bid to be reelected to the House of Commons. In 1782, he was named lieutenant-general of the ordnance and appointed to the Privy Council. His colonelcy was transferred from the 23rd Fusiliers to the 19th Light Dragoons in 1786. He resumed limited active duty in 1789 when a crisis with Spain over territorial claims in northwestern North America threatened to boil over into war.

The crisis was resolved, and Howe did not see further action until 1793, when the French Revolutionary Wars involved Britain. He was promoted to full general in 1793 and commanded several outposts in the defense of Britain through at least 1795. That year, he was appointed the governor of Berwick-on-Tweed.

When his brother Richard died in 1799 without surviving male issue, Howe inherited the Irish titles and became the 5th Viscount Howe and Baron Clenawly. In 1803, he resigned as lieutenant-general of the ordnance, citing poor health. In 1805, he was appointed the governor of Plymouth and died at Twickenham in 1814 after a long illness.

He was married in 1765 to Frances Connolly, but the marriage was childless, and his titles died with him. His wife survived him by three years; both are buried in Twickenham.

Outside Sources

- Wikipedia - William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe

- Find a Grave - William Howe

- William L Clements Library - William and Richard Howe Letters

- The History Junkie's Guide to American Revolutionary War Generals

- The History Junkie's Guide to the American Revolutionary War

- The History Junkie's Guide to the Battle of Bunker Hill

- The History Junkie's Guide to the Battle of Brandywine