Samuel Huntington was born in Windham, Connecticut Colony, and was sent to the common schools as a boy. He was limited in his education and was self-educated for most of his education.

When he was 16 years old, he apprenticed to a cooper while also helping on his father's farm.

Jump to:

Samuel Huntington's Early Career and Work during the American Revolution

Although he was self-educated, he was extremely intelligent.

He was admitted to the bar and began practicing law in Norwich, Connecticut. Once he had established a career and an income, he married Martha Devotion whom he would have no children.

However, after the passing of his brother, the couple would adopt the children and raise them as their own.

Politically, Samuel worked hard. His calm demeanor and diligence allowed him to rise through the ranks.

When John Jay became a minister to Spain, Samuel became the president of the Second Continental Congress.

Post-Revolution

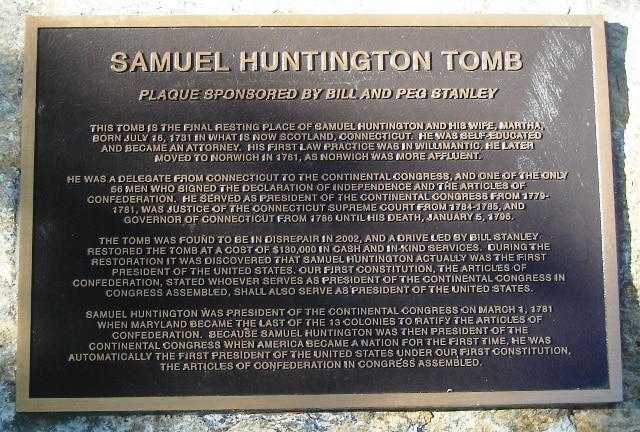

During this time, the Articles of Confederation would be written, and Huntington, being the President of the Continental Congress, would be the "first president" of the United States. This is a mere technicality.

The Articles of Confederation was a weak government, and it was not until the Constitution was written that there would be a President who was elected by the people.

The first President under the Constitution was George Washington.

In 1786, he was elected Governor of Connecticut. After the Articles of Confederation failed, the Constitution was ratified. Huntington aided Connecticut's ratification of the Constitution in 1788.

He would survive another 8 years as Connecticut's governor and die in office.

Legacy

Charles Goodrich had this to say in his book Lives of the Signers of the Declaration

On the public character or the public services of Governor Huntington, it is unnecessary to enlarge.

It is pleasant, however, to mark the progress of such a man from obscurity to the exalted and dignified walks of life, and from the humble occupation of a plough boy, to the deep and learned investigations of the judge, and to the wise and sagacious plans of the statesman.

What was true of Mr. Huntington, in this respect, was true of a great proportion of that phalanx of patriots who, during the days of our revolutionary struggle, opposed themselves with success to British exactions and British oppressions.

They came from humble life. They rose by the force of their native genius. Obstacles served only to rouse their latent strength. They threw aside discouragements as the skilful swimmer dashes aside the waters which impede his course.

Mr. Huntington was one of these men. He had not the advantage of family patronage or the benefit of a liberal education, nor did hereditary wealth lend him her aid.

But, instead of these, he had genius, courage, and perseverance. With the united assistance of these, he entered upon his professional course and, afterwards, on his political career.

He rendered services to his country, which will long be remembered with gratitude; be attained to honors with which a high ambition might have been satisfied; and, at length, went down to the grave, cheered with the prospect of a happy immortality.