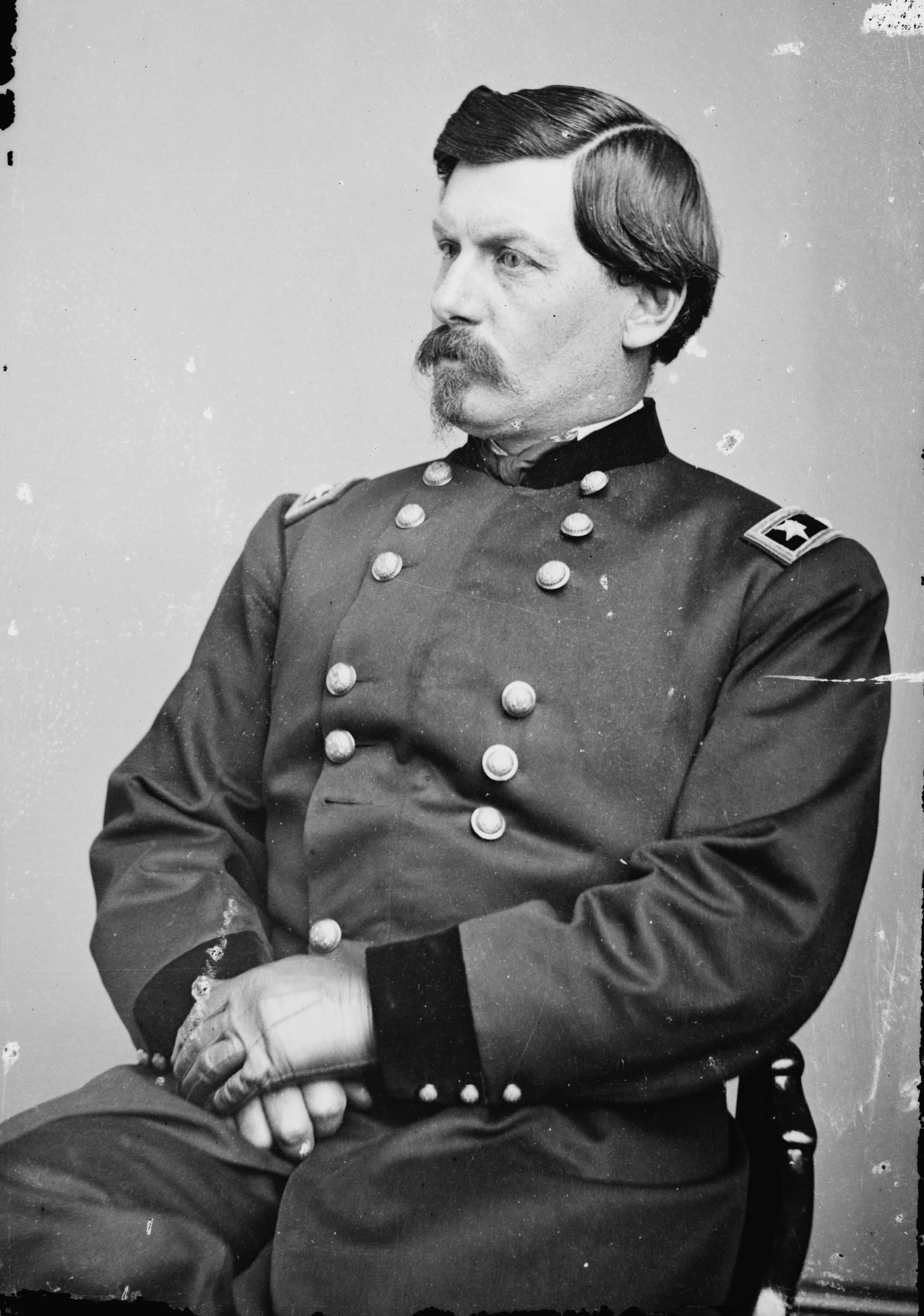

George McClellan was an American soldier, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician. He was a graduate of West Point and served with distinction during the Mexican-American War, and became a successful railroad executive after the war was over.

He joined the Union Army when war broke out and quickly rose up the ranks. He caught the eye of Abraham Lincoln and was given the position of General-in-chief and command of the entire Union Army.

McClellan organized and led the Union army in the Peninsula Campaign in southeastern Virginia from March through July 1862. It was the first large-scale offensive in the Eastern Theater.

Making an amphibious clockwise turning movement around the Confederate States Army in northern Virginia, McClellan's forces turned west to move up the Virginia Peninsula, between the James and York Rivers, landing from the Chesapeake Bay, with the Confederate capital, Richmond, as their objective.

Initially, McClellan was somewhat successful against the equally cautious General Joseph E. Johnston, but the military emergence of General Robert E. Lee to command the Army of Northern Virginia turned the subsequent Seven Days Battles into a partial Union defeat.

After his defeat, he and Abraham Lincoln engaged in a long political feud that resulted in McClellan being fired twice from his command and eventually running against President Lincoln in the 1864 Presidential Election.

Early Life and Career

George McClellan was born into wealth. His father was a prominent surgeon in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and the founder of the Jefferson Medical College.

His mother was from a leading family in Pennsylvania and was known for her grace and refinement.

His family had been in America since its founding, and he was the great-grandson of the Revolutionary War general Samuel McClellan.

He was educated at the University of Pennsylvania to begin a study in law, which he then changed to the study of war. His father was able to pen a letter to President John Tyler to get young George into the United States Military Academy.

At West Point, he was an energetic and ambitious cadet, deeply interested in the teachings of Dennis Hart Mahan and the theoretical strategic principles of Antoine-Henri Jomini.

His closest friends were aristocratic Southerners such as James Stuart, Dabney Maury, Cadmus Wilcox, and A. P. Hill.

These associations gave McClellan what he considered to be an appreciation of the Southern mind and an understanding of the political and military implications of the sectional differences in the United States that led to the Civil War.

He graduated in 1846, second in his class of 59 cadets, losing the top position to Charles Seaforth Stewart only because of poor drawing skills. He was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Mexican-American War

It was not long after his graduation that young McClellan received an order to sail to Mexico, where he would take part in the Mexican-American War.

During the conflict, he would make many new friends and was influenced by the Major Generals of the war. Men such as Winfield Scott and Zachary Taylor would influence the strategies he would use during the Civil War.

He learned that flanking movements (used by Scott at Cerro Gordo) are often better than frontal assaults and the value of siege operations (Veracruz).

He witnessed Scott's success in balancing political with military affairs and his good relations with the civil population as he invaded, enforcing strict discipline on his soldiers to minimize damage to property. McClellan also developed a disdain for volunteer soldiers and officers, particularly politicians who cared nothing for discipline and training.

Peacetime

The years leading up to the Civil War and even the years after were ideal times for military men to build a reputable name during peacetime.

There were still plenty of areas in the United States that needed to be explored, and Indians still inhabited much of the West. Although peacetime bored McClellan, he was still able to gain some success in various expeditions and then apply that experience to the railroad industry.

Returning to the East, McClellan began courting his future wife, Mary Ellen Marcy (1836–1915), the daughter of his former commander. Ellen, or Nelly, refused McClellan's first proposal of marriage, one of nine that she received from a variety of suitors, including his West Point friend, A. P. Hill. Ellen accepted Hill's proposal in 1856, but her family did not approve, and he withdrew.

In June 1854, McClellan was sent on a secret reconnaissance mission to Santo Domingo at the behest of Jefferson Davis. McClellan assessed local defensive capabilities for the secretary. Davis was beginning to treat McClellan almost as a protégé, and his next assignment was to assess the logistical readiness of various railroads in the United States, once again with an eye toward planning for the transcontinental railroad. In March 1855, McClellan was promoted to captain and assigned to the 1st U.S. Cavalry Regiment.

Because of his political connections and his mastery of French, McClellan received the assignment to be an official observer of the European armies in the Crimean War in 1855. Traveling widely and interacting with the highest military commands and royal families, McClellan observed the siege of Sevastopol. Upon his return to the United States in 1856, he requested an assignment in Philadelphia to prepare his report, which contained a critical analysis of the siege and a lengthy description of the organization of the European armies.

He also wrote a manual on cavalry tactics that was based on Russian cavalry regulations. Like other observers, though, McClellan did not appreciate the importance of the emergence of rifled muskets in the Crimean War and the fundamental changes in warfare tactics it would require.

The Army adopted McClellan's cavalry manual and also his design for a saddle, dubbed the McClellan Saddle, which he claimed to have seen used by Hussars in Prussia and Hungary. It became a standard issue for as long as the U.S. horse cavalry existed and is still used for ceremonies.

Civilian Pursuits

McClellan resigned his commission on January 16, 1857, and, capitalizing on his experience with railroad assessment, became chief engineer and vice president of the Illinois Central Railroad and then president of the Ohio and Mississippi Railroad in 1860. He performed well in both jobs, expanding the Illinois Central toward New Orleans and helping the Ohio and Mississippi recover from the Panic of 1857. Despite his successes and lucrative salary, he was frustrated with civilian employment and continued to study classical military strategy assiduously. During the Utah War against the Mormons, he considered rejoining the Army. He also considered service as a filibuster in support of Benito Juárez in Mexico.

Before the outbreak of the Civil War, McClellan became active in politics, supporting the presidential campaign of Democrat Stephen A. Douglas in the 1860 election. He claimed to have defeated an attempt at vote fraud by Republicans by ordering the delay of a train that was carrying men to vote illegally in another county, enabling Douglas to win the county.

In October 1859, McClellan was able to resume his courtship of Mary Ellen, and they were married in Calvary Church, New York City, on May 22, 1860.

Civil War

George McClellan is one of the mysteries of the Civil War.

Unlike many of his colleagues who were abolitionists, he did not support federal involvement in state affairs. He believed that the federal government should not interfere with slavery. His stance was so strong on this issue that when the Civil War broke out, he was recruited to become a Confederate General. However, as much as he disagreed with federal involvement with slavery, he liked secession even less. He would join the Union and become an important name at the beginning of the war.

McClellan's knowledge of the railroad made many believe that he would be excellent at logistics. He was highly sought to take command of state militias until settling in Ohio. This appointment did not last long as he would eventually become general-in-chief after the First Battle of Bull Run, but it was during his command in Ohio when he began lobbying a former mentor, Winfield Scott, for a great position in the war.

As McClellan scrambled to process the thousands of men who were volunteering for service and to set up training camps, he also applied his mind to grand strategy. He wrote a letter to Gen. Scott on April 27, four days after assuming command in Ohio, that presented the first proposal for a strategy for the war. It contained two alternatives, each envisioning a prominent role for himself as commander. The first would use 80,000 men to invade Virginia through the Kanawha Valley toward Richmond.

The second would use the same force to drive south instead, crossing the Ohio River into Kentucky and Tennessee. Scott rejected both plans as logistically unfeasible. Although he complimented McClellan and expressed his "great confidence in your intelligence, zeal, science, and energy," he replied by letter that the 80,000 men would be better used on a river-based expedition to control the Mississippi River and split the Confederacy, accompanied by a strong Union blockade of Southern ports.

This plan, which would require the considerable patience of the Northern public, was derided in newspapers as the Anaconda Plan but eventually proved to be the outline of the successful prosecution of the war. Relations between the two generals became increasingly strained over the summer and fall.

Civil War Service

George McClellan began his Civil War ascension at the Battle of Philippi and ended in disgrace when President Lincoln fired him. Here is a list of his involvement in the Civil War.

- Battle of Philippi - Union victory, but was strategically worthless and gave the Union false confidence.

- Organization of the Army - Regardless of what happened with McClellan during the Civil War, he earned high marks with his organization of the Army. The Army that Ulysses S. Grant pounded Lee with was organized by McClellan.

- Peninsula Campaign - The plan made sense, but he was too cautious in executing it. His army would be dominated by Robert E. Lee during the Seven Days Battles. McClellan was relieved of his command.

- Maryland Campaign - After the meeting disaster, Pope was relieved of his command, and McClellan was reinstated. His ability to mend and organize an army was exceptional, and he was able to do so here as well. His army saw success at the Battle of Antietam but did not pursue Lee after his victory. This led to his removal a second time.

- 1864 Presidential Election - After a lengthy feud with Lincoln, he became a political opponent in the election of 1864. He was defeated easily and left the country with his family to travel to Europe.

Later Life

McClellan was appointed chief engineer of the New York City Department of Docks in 1870. Evidently, the position did not demand his full-time attention because, starting in 1872, he also served as the president of the Atlantic and Great Western Railroad.

He and his family then embarked on another three-year stay in Europe (1873–75)

In March 1877, the Governor of New York, Lucius Robinson, nominated McClellan as the first Superintendent of Public Works, but the New York State Senate rejected him as "incompetent for the position".

In 1877, the Democrats nominated McClellan for Governor of New Jersey, an action that took him by surprise because he had not expressed an interest in the position.

He accepted the nomination, won the election, and served a single term from 1878 to 1881, a tenure marked by careful, conservative executive management and by minimal political rancor.

The concluding chapter of his political career was his strong support in 1884 for the election of Grover Cleveland. He sought the position of Secretary of War in Cleveland's cabinet, for which he was well qualified, but political rivals from New Jersey succeeded in blocking his nomination.

McClellan devoted his final years to traveling and writing; he produced his memoirs, McClellan's Own Story (published posthumously in 1887), in which he stridently defended his conduct during the war.

He died unexpectedly of a heart attack at age 58 in Orange, New Jersey, after suffering from chest pains for a few weeks. His final words, at 3 a.m., October 29, 1885, were, "I feel easy now. Thank you." He was buried at Riverview Cemetery, Trenton, New Jersey