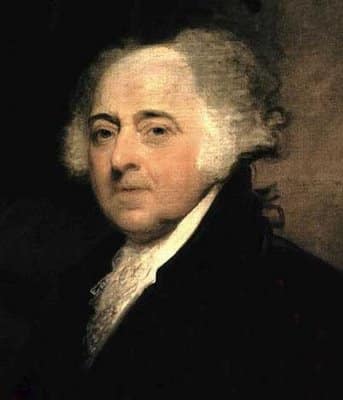

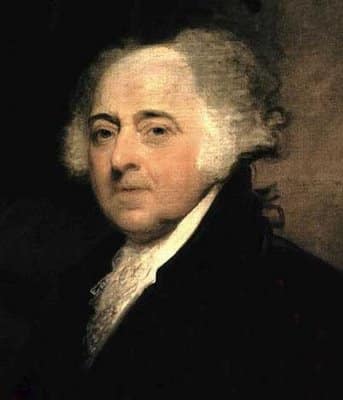

John Adams (October 30, 1735 - July 4, 1826), the Second President of the United States, was born in Braintree, Massachusetts.

His father, who shared his name, was a farmer, lieutenant in the militia, and a Congregationalist deacon. Adams was the oldest of his three brothers and the first Adams to attend college.

Jump to:

Early Life

He inherited a ferocious work ethic from his father and worked his way through school. Although he did not come from a rich family, he attended Harvard and taught school for a few years. His father had hopes of him becoming a pastor. However, Adams chose a life within the law instead.

He was admitted to the bar and studied under an affluent attorney named James Putnam. It was here that he became passionate about the 13 Original Colonies after hearing an argument that James Otis gave.

John would marry Abigail Smith (1744-1818) on October 25, 1764.

Abigail and John Adams would become the most famous couple in American history.

The two had six kids:

- Abigail (1744-1813),

- John Quincy (1767-1848),

- Susanna (1768-1770),

- Charles (1770-1800),

- Thomas (1772-1832)

- Elizabeth (stillborn)

For most of his young life, Adams was unknown except to those around him. It would be the Stamp Act and the Boston Massacre that would catapult him onto the international stage.

Early Career

After the French and Indian War (Seven Years War in England), Great Britain was in a large amount of debt. In order to pay for these debts, they began to tax the colonies. The first of these taxes was the Stamp Act of 1765.

The Stamp Act was met with fierce opposition and eventually lifted. Many influential men made their mark during these protests and emerged as leaders of the American Revolution.

One of these men was Adams. He anonymously wrote four essays (one of which was A Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law) for the Boston Gazette. These essays argued that the Protestant ideas that had brought the Puritans to found the Massachusetts Bay Colony were the same ideas that were behind the colonists' resistance to the Stamp Act.

He also penned the Braintree instructions, which were a defense of the rights of the colonists.

Adams then delivered a speech before the governor and council condemning the Stamp Act. He argued that since Massachusetts did not have representation in Parliament, the British did not have the right to levy taxes upon them.

Although he was not the first to come up with the phrase, this is an example of the "no taxation without representation" attitude that was prevalent in the colonies.

Five years later, the same man who had defended colonial liberties so passionately was the same man who represented the British soldiers in the Boston Massacre Trial. After an incident in the street that resulted in the British soldiers firing into a mob of unarmed Bostonians, the British soldiers had trouble finding counsel.

John Adams, always a loyal servant of the law and not public opinion or his cousin Samuel Adams, took the case and represented the men. Ironically, the man prosecuting the soldiers was Robert Treat Paine, who would later sign the Declaration of Independence alongside Adams.

John fought hard and won the case. Six of the soldiers were acquitted, and two were convicted of murder, which was brought down to manslaughter. His popularity and practice took a huge hit because of the case.

Regardless, four years later, Massachusetts sent Adams to the First Continental Congress

American Revolutionary War

Adams was a short, chubby man who had a hard time holding his tongue. His passion for truth often offended, and he was viewed by most as obnoxious. Regardless, there is no disputing his influence on Congress.

The Second Continental Congress can be argued as John Adams's finest hour. He met and befriended a young radical named Thomas Jefferson. Seeing the talent that Jefferson had in his pen, Adams suggested that he write the Declaration of Independence.

He, of course, did, and John Adams, Roger Sherman, Philip Livingston, and Benjamin Franklin edited it. Adams understood that a new Declaration should come from a Virginian, which Jefferson was.

He would also nominate George Washington to be the general of the Continental Army. He did this and upset his fellow Massachusetts man, John Hancock, who believed that Adams would nominate him.

However, Adams realized the capability of Washington along with the politics. Washington was a Virginian, and Virginia was the largest and most influential colony of all thirteen colonies. He understood that the leader of the Continentals should come from there.

Washington's nomination united the northern, middle, and southern colonies since he was known for his great character and was a slave owner.

Politically, Washington was perfect for the job. Nobody knew how valuable he actually would be, but it should be noted that it was Adams who saw the potential in him first.

John Adams was labeled as the voice of the Revolution, and Thomas Jefferson was labeled the pen. These two struck up a friendship during this period. This friendship would continue up until Adams' Presidency and then continue again once Abigail died.

During the American Revolutionary War, John Adams served as a diplomat to France and the Netherlands. He and Franklin served together in France, and the two did not get along. Adams was much too unbending and too confrontational for the French.

He was unsuccessful in France and was sent to the Netherlands for the duration of the war. He saw some success in the Netherlands. He would then return to France and then to England after the war.

This time away would leave him out of the Constitutional Convention. Ironically, two of the most influential men during the Revolution would not influence the United States Constitution.

John Adams Facts: Presidency

Read Full Article: President John Adams Facts and Timeline

John Adams was elected President in 1796, in which he succeeded George Washington and defeated his old friend, Thomas Jefferson.

This was an important part of American history in that it was the first time in the young republic's life that a precedent would be set in the transfer of power. America had been set up by a rule of the consent of the governed and not ruled by a royal family.

There were questions about how the losers would respond to the defeat. Would they try and seize power, or would they let it go? The transition was seamless and set a precedent for future Presidents.

His term would be tumultuous, and he would not be an effective president. The nation was beginning to shift from the Federalists to the Jeffersonian Democrats.

While Adams tried to stay neutral and disliked the Federalist leader Alexander Hamilton, he was viewed as one of them. His Alien and Sedition Act put a nail in his political career.

In hindsight, Adams's work on the United States Navy and the ability to keep the United States out of a war with France was vital to the survival of the young Republic.

Jefferson defeated Adams in the election of 1800. The election was a hard-fought campaign in which both candidates attacked each other personally. Afterward, the friendship of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson ended.

Abigail Adams would die without ever forgiving Jefferson for what he had accused her husband. The night before he left office, Adams did his famous Midnight appointees.

The Final Years of John Adams

After Jefferson left office, Adams became more vocal again. He wrote a series of letters that debunked Alexander Hamilton's 1800 pamphlet.

He also launched attacks on his character. At this time, Hamilton was already dead from the infamous duel with Aaron Burr.

Benjamin Rush reunited John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. Rush was communicating with both of them and, by way of letter, re-introduced them.

The two revolutionaries, now older men, put aside their political differences and began a series of letters that is hailed as one of the greatest writings in American History.

The two letters shared by these men allow us to look into the minds of these electric founders. These men were the best of friends, fellow diplomats, political rivals, enemies, and then friends again.

John Adams' son Charles died in 1800 from alcoholism, his daughter Abigail died of breast cancer in 1813, and finally, his beloved Abigail died of typhoid in 1818.

Adams wrote of her passing with great emotion to Jefferson.

In a life of irony, the John Adams biography ended on July 4, 1826, the 50th birthday of the nation that he helped found. His last words were, "Thomas Jefferson survives," which was false.

Jefferson had died on the same day, a few hours before Adams. Thus tying these two patriots together forever. Once Adams died, only Charles Carroll survived as the last of the Declaration of Independence signers.

John Adams lived long enough to see his son, John Quincy Adams, elected as the sixth President of the United States.