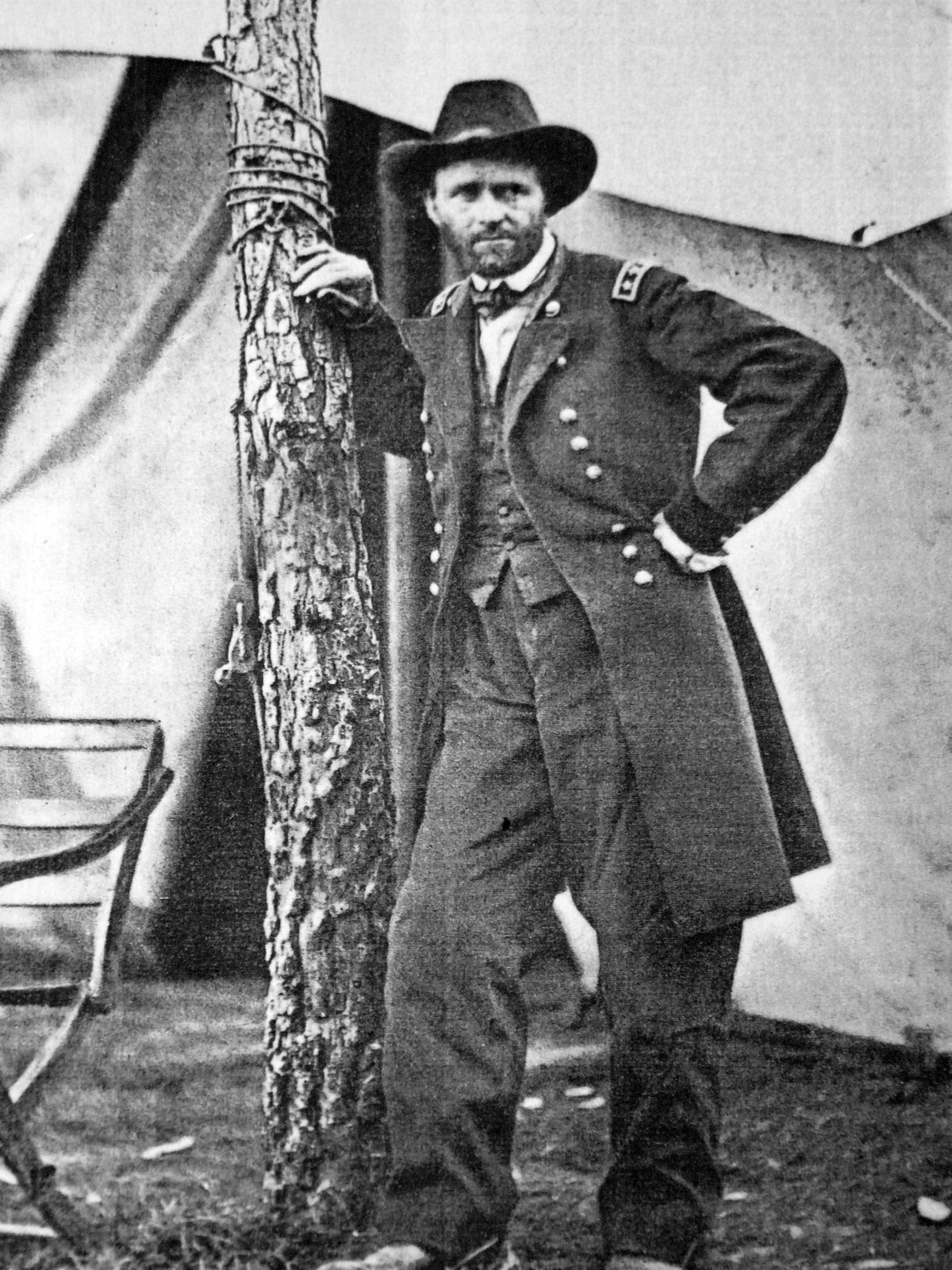

Ulysses S. Grant was the Union General who prevailed in the grueling but successful war of attrition against Robert E. Lee and who won fame for his victories at Ft. Donaldson (1862), Shiloh (1862), and Vicksburg (1863). Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox in April 1865, ending the American Civil War.

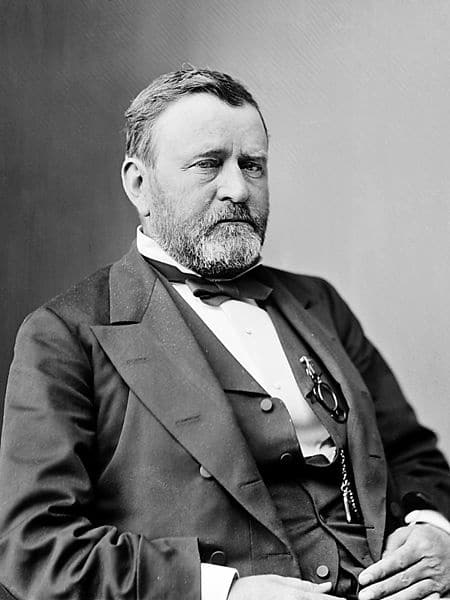

Grant was also the 18th President of the United States of America, serving from 1869 to 1877. Near bankruptcy and dying of throat cancer, Grant then wrote a brilliant memoir of his military service; it stands as a monument in military historiography, and his battlefield achievements rank him as one of the finest generals in world history.

As a Republican president, he supported the Radical Republicans in the program for reconstruction, defeated the Ku Klux Klan, and supported civil rights for the Freedmen (freed slaves). In foreign policy, he settled a major conflict with Britain regarding the Civil War.

Although personally honest, Grant gave out patronage too generously to his loyalists and protected senior corrupt officials. The Panic of 1873 made his second term one of economic depression and allowed the Democrats to regain control of the House in 1876. Grant made a celebrated tour around the world but came back in 1880 to try for a third term and failed.

Grant was not religious, though not opposed to it either. His wife was a devout Christian. Grant was charitable in the settlement terms for the Confederate soldiers, whom he allowed to keep their horses and return to their farms.

Early Life

Grant was born on April 27, 1822, in a two-room cabin at Point Pleasant, Ohio. His father, Jesse Root Grant, was descended from undistinguished Puritan forebears who had immigrated to Massachusetts Bay Colony in the early 17th century. His mother, Hannah Simpson Grant, was a typical hard-working and pious frontier woman. The elder Grant was a tanner who, by hard work and native shrewdness, managed to acquire a modest competence. Lacking much education himself, he was determined that his sons should have the best the community offered.

From the time he was 6 until he was nearly 17, young Grant regularly attended school, first in Georgetown, Ohio, to which the family had moved soon after he was born, and later at nearby academies. While working on the family, he developed a fondness for horses, almost amounting to a passion and a liking for outdoor life that, after years, stood him in good stead.

In 1839, his father obtained for him an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point, at which, due to an error made by a United States senator (Thomas Morris of Ohio), he was entered onto the rolls of the Academy as Ulysses S. Grant instead of his birth name.

All attempts to have the error rectified were fruitless, so he accepted and used the new name, the end result of which his new Academy friends would recognize his initials for what they seemed to be and call him "Sam." Years later, he would tell a friend what the initial for his middle name stood. "In answer to your letter of a few days ago asking what ‘S’ stands for in my name," he said, "I can only state nothing."

Except for his horsemanship, Grant did not distinguish himself at West Point, which had an engineering curriculum. Graduating in 1843, twenty-first in a class of thirty-nine, he was sent to the infantry instead of to the cavalry as he would have preferred. He served at various posts in Missouri and Louisiana, but in 1845, he was ordered to accompany General Zachary Taylor to Texas and later served in the Mexican-American War.

Subsequently, he was transferred to General Winfield Scott's army in time to participate in the march on Mexico City. Grant handled logistics and did not have a combat role, but he was twice cited for gallantry under fire. He was an unusually keen observer of terrain, battle formations, and the actions of commanders, and by happenstance, was involved in most of the major battles of the war. In later years, he said it was an unjust war, but he did not say that at the time.

Stationed at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, after the Mexican War in August 1848, he married Julia Dent, daughter of a Missouri planter and slaveowner. Four years later, now a captain, Grant was transferred to Fort Humboldt in far northern California; his wife could not accompany him because of the hardships of the trip.

Unhappy because of the loneliness and enforced separation, Grant, still a first lieutenant, started drinking. "I do nothing here but set in my room and read and occasionally take a short ride on one of the public horses," he wrote his wife. His commander, Lt Col. Robert C. Buchanan, hated him and forced him to resign.

The six years that followed were the most disappointing of his life. He tried farming on land in the St. Louis area owned by his wife's father. He failed at that, at selling real estate, and at clerking in a customs house. In financial straits, he finally turned to his own family and became a clerk in a Galena, Illinois, leather store owned by his two brothers.

Civil War

Ulysses S. Grant would have died in obscurity if not for the Civil War. However, each year, he proved himself and eventually drew the attention of Abraham Lincoln.

1861-62

As the demand for West Point graduates increased after the start of the Civil War, Grant rejoined the army. As the chief trainer of Illinois regiments, he attracted immediate attention for his striking command skills and was soon given control of Union forces in southern Illinois.

After Grant's early successes, Henry Halleck, his commanding general, became jealous and removed him from his command. Halleck stopped trying to discredit Grant when he and Grant found a common cause in countering General John McClernand's independent efforts to preempt Grant's operations in the Mississippi Valley in October 1862 without Halleck's approval. Washington was watching closely and soon gave Grant another field command.

It was during these years he gained the nickname "The Butcher" due to the losses he took at the Battle of Shiloh.

Vicksburg

In 1862-63, after a long, arduous campaign against five poorly coordinated Confederate armies, Grant captured Vicksburg on July 4, 1863, giving the Union control of the entire Mississippi River, which permanently cut off Texas and Arkansas from the rest of the Confederacy.

In a major campaign in the Mississippi swamps, Grant defeated Confederate General John C. Pemberton's army and freed the way for him to capture Jackson, the capital of Mississippi. Then, looping back, he forced Pemberton's army into Vicksburg in the Battle of Champion's Hill on 16 May 1863. With help from Admiral David D. Porter's gunboats, he captured Vicksburg after a month-long siege and bombardment, which nearly ruined the city.

Late in the year, Lincoln gave Grant command of the entire United States Army.

1864-65

Strategy

Grant took command of all the Union armies on March 9, 1864, and had to think out a war-winning strategy. He had already been discussing ideas with Halleck, the chief of staff based in Washington. Halleck was now subordinate to Grant and worked to implement Grant's ideas. Grant's strategy entailed complex coordination within and between theaters. He wanted not only to attack the enemy's armies but also to sever their logistical ties. It was a bold plan that relied more on maneuver than bloody engagements.

In the West, Grant assigned the major thrust to his ablest general and good friend, William T. Sherman. Sherman was to use three armies and advance from Chattanooga against General Joseph E. Johnston's Confederate Army of Tennessee and push toward Atlanta, the region's vital railroad center.

Grant made clear the campaign's primary objective: "You, I propose to move against Johnston's army, to break it up and get into the interior of the enemy's country as far as you can, inflicting all the damage as you can against their war resources." The conduct of the operation Grant left to Sherman.

Grant wanted a joint army-navy expedition against Mobile, the Confederacy's remaining major port on the Gulf of Mexico. Lincoln, however, was concerned with Reconstruction and insisted on a movement up the Red River in Louisiana to strengthen the efforts of the state's Unionists' to create a new state government. Major General Nathaniel P. Banks, an officer with powerful political connections and a favorite of Lincoln's, commanded the movement, which was a major fiasco; Banks was defeated and narrowly managed to get his army out.

In the East, Grant first planned to invade North Carolina and cut off Richmond. Lincoln insisted that Richmond had to be the target, so Grant decided on a three-pronged offensive in Virginia. The main Union combat army (nominally under George Meade but with Grant in actual control) would attack the Confederacy's premier force, General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia.

Simultaneously, Grant ordered separate forces to cut Lee's railroads (a partial success) and to destroy Lee's supply base by laying waste to the farms in Virginia's Shenandoah Valley (a major success). He sent Major General Benjamin F. Butler to cut the rail lines leading into Richmond from the South, but Butler failed badly.

1864-65 campaigns

Beginning with the Battle of the Wilderness in the summer of 1864, Grant pressed the Confederate Army through a series of battles that made up the Overland Campaign. By June, the two armies were settled in entrenchments around the important city of Petersburg, Virginia. After a long siege, Grant successfully broke the Confederate supply lines, forcing them to retreat in the Appomattox Campaign.

Robert E. Lee eventually surrendered at Appomattox Court House.

Following the conclusion of the war, Grant remained on active duty and was promoted to become the first four-star general in the history of the United States Army. Commanding the entire Army, Grant was responsible for operations in the Western U. S. against Native Americans until he resigned his commission to become President in early March 1869.

Ascension to the Presidency

Full Article: President Ulysses S. Grant Facts and Timeline

With the assassination of Lincoln as the war ended, Grant had enormous military and political authority, but he was slow to use it. President Andrew Johnson tried, especially during the elections for Congress in 1866, to use Grant's prestige to bolster the faltering presidency.

Grant, sympathetic to his black soldiers, moved toward the Radical Republicans who were determined to block Johnson's lenient policy toward the South.

The Radicals put Grant's army back in control of the South in 1867, as Radical Reconstruction began. Grant's enormous prestige made him the nearly unanimous choice for the Republican presidential nomination in 1868, and he easily defeated Horatio Seymour, the Democrat who ran on a white supremacy platform.

He would go on to win two terms as President. Winning the elections of 1868 and 1872.

Later Years

After leaving office, he decided to run for president again in 1880 as a Stalwart. He gained the support of most of them, including Roscoe Conkling. He ran against Half-Breed James G. Blaine at the convention. Neither side won, so a "compromise candidate," Half-Breed James Garfield, was nominated, and the Stalwart Chester A. Arthur was nominated for the Vice Presidency to "balance out" the ticket.

In the summer of 1884, he complained of throat soreness, and in October of that year, he was diagnosed with throat cancer. In a poor financial situation, Grant worried about how his wife would carry on once he died.

Fortunately, Mark Twain offered him 70% of royalties if he would allow him to publish his memoirs. He did, and died in July 1885 with his last spoken words being "water", asking for that so that his painful throat would feel better.