William Weatherford is not a name you hear in school.

Even though you do not hear the name, his name is synonymous with Squanto, Chief Massasoit, Tecumseh, Joseph Brant, and Geronimo you may have heard of prior, but he was a warrior-chief who loved his people.

Jump to:

He is one of many mixed-race descendants of Southeast Indians who intermarried with European traders and later colonial settlers. William Weatherford was of mixed Creek, French, and Scots ancestry. He was raised as a Creek in the matrilineal (this was his mother's descendants and not the father's) nation and achieved his power in it through his mother's prominent Wind Clan.

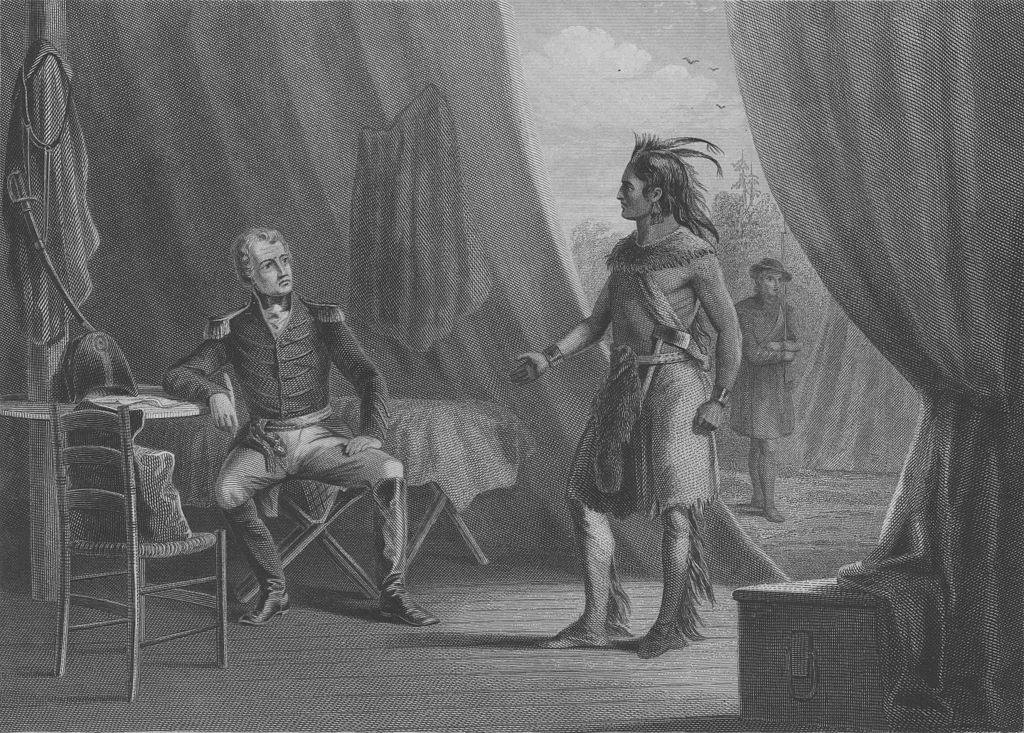

He would have a famous exchange with General Andrew Jackson at the end of the war he was fighting.

After the war, he would become a slaveholder, rebuild his life as a plantation owner, and assimilate into American culture.

Early Life

William Weatherford was born in 1781 in Alabama near Creek territory. His mother was a Native American daughter of a Creek Chief from the "Tabacha clan," which was the most powerful of the Creek clans, which were also known as the "Wind Clan."

His father, Charles Weatherford, was originally from Scotland and had come to America to earn a better living. He befriended the chieftain and married his daughter after the death of her first husband. William Weatherford's mother's name was Sehoy III, and due to the matrilineal kinship system that the Creek recognized, the children were accepted by her clan.

President Thomas Jefferson appointed Benjamin Hawkins as Superintendent of Indian Affairs, which was south of the Ohio River, still considered the frontier in America.

As a boy, William Weatherford was called "Billy". After he showed his skill as a warrior, he was given the "war name" of Hopnicafutsahia, or "Truth Teller.

"He was the great-grandson of Captain Jean Marchand, the French commanding officer of Fort Toulouse, and Sehoy I, a Creek of the Wind clan. On his mother's side, he was a nephew of the mixed-race Creek chief, Alexander McGillivray, who was prominent in the Upper Creek towns.

Through his mother's family, Weatherford was a cousin of William McIntosh, who became chief of the Lower Creek towns.

The Lower Creek, who comprised the majority of the population, lived closer to the European Americans and intermarried with them, adopting more of their ways, as well as connecting to the market economy.

Career

William Weatherford had an interesting mix of skills that would serve him well.

He was an excellent orator strategist and always seemed to have perspective on the events surrounding him.

William Weatherford learned the traditional Creek ways and language from his mother and clan. He also learned the English ways and language from his father. He was well-educated but aligned himself with his native heritage more than his father's.

His father was a slave owner, and as a young man, he also acquired slaves, planted commercial crops, and bred and raced horses. He was not the typical Indian that was struggling to survive.

Even with his European roots and the good relations he shared with both English and Europeans, he noticed the encroaching of settlers on his native tribes' land.

The Creek of the Lower Towns were becoming more assimilated, but the traditional elders and the people of the Upper Creek towns (Weatherford identified with the Lower Creeks) were more isolated from the European-American settlers.

They kept more traditional ways and opposed the new settlements. Weatherford and other Upper Creek leaders resented the encroachment of settlers into their traditional Upper Creek territory, principally in what the United States of America called the Mississippi Territory, which included their territory in present-day Alabama.

In 1811, Weatherford would experience more pressure when the Americans began to improve the Trading Path and National Road. These improvements allowed more settlers and more encroachment.

The Upper Creeks would not relinquish what they believed was rightly theirs. However, their actions would become a lightning rod at the Battle of Fort Mims when hundreds of Americans were slaughtered.

The Lower Creek were among the Five Civilized Tribes who adopted some European-American style farming practices and other customs. As a result, most of the Creek managed to continue as independent communities while slowly becoming almost indistinguishable from other frontier families.

The Upper Creek towns resisted the changes in the territory. In these debates, Weatherford counseled neutrality in the rise of hostilities. Conflict broke out within the Creek Nation between those who were adapting to assimilation and those trying to maintain the traditional leadership.

After the Massacre of Fort Nims and the Indian Massacre that followed the Great Indian Chief surrendered himself to Andrew Jackson and gave a fascinating speech.

Ironically, the tribe that helped defeat and make Jackson a wealthy man was the Cherokee, who helped defeat the tribes in Florida.

Personal Life

William Weatherford married Mary Moniac (c. 1783 – 1804), who was also of mixed race. They had two children, Charles and Mary (Polly) Weatherford. After Mary's death, Weatherford married Sopethlina Kaney Thelotco Moniac (c. 1783 – 1813).

She died after the birth of their son, William Weatherford, Jr., born 25 December 1813. About 1817, Weatherford married Mary Stiggins (c. 1783-1832), who was of Natchez and English heritage. They also had children, Alexander McGillivray Weatherford, Mary Levitia Weatherford, Major Weatherford (who died as a child), and John Weatherford.

Weatherford's nephew, David Moniac, son of his sister Elizabeth Weatherford, was the first Native American graduate of the United States Military Academy.

William Weatherford may have been a blood relative of the Shawnee Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa, whose mother and father were of Creek and Shawnee lineages. Their relationship may have been the foundation of the strong alliance between Chief Red Eagle and Chief Tecumseh during the Indian Wars and War of 1812.