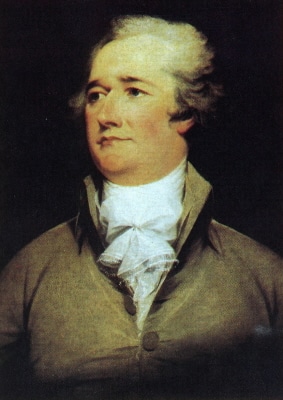

Alexander Hamilton was one of the most influential, conservative, and nationalistic of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He was born outside of the 13 original colonies in the Caribbean to a questionable family and rose to prominence during his service in the Continental Army and eventually became one of the greatest American intellectuals ever.

One of the more interesting Alexander Hamilton facts is that the America we live in is Hamilton's ideals more than Thomas Jefferson's, despite Jefferson's place in American History. His life was cut down early due to his famous duel with Aaron Burr.

Jump to:

Early Life

Alexander Hamilton was born in and spent part of his childhood in Charlestown, the capital of the island of Nevis, in the Leeward Islands; Nevis was one of the British West Indies.

Hamilton was born out of wedlock to Rachel Faucette, a married woman of partial French Huguenot descent, and James A. Hamilton, the fourth son of the Scottish laird Alexander Hamilton of Grange, Ayrshire.

His mother moved with the young Hamilton to St. Croix in the Virgin Islands, then ruled by Denmark.

It is not certain whether the year of Hamilton's birth was 1757 or 1755; most historical evidence after Hamilton's arrival in North America supports the idea that he was born in 1757, and many historians have accepted this birth date.

Hamilton listed his birth year as 1757 when he first arrived in the 13 original colonies. He celebrated his birthday on January 11.

Hamilton's mother had been married previously to Johann Michael Lavien of St. Croix. Rachel left her husband and first son, Peter, traveling to St. Kitts in 1750, where she met James Hamilton.

Hamilton and Rachel moved together to Rachel's birthplace, Nevis, where she had inherited property from her father. The couple's two sons were James Jr. and Alexander.

Because Alexander Hamilton's parents were not legally married, the Church of England denied him membership and education in the church school. Hamilton received "individual tutoring" and classes in a private school led by a Jewish headmistress. Hamilton supplemented his education with a family library of 34 books.

James Hamilton abandoned Rachel and their sons, allegedly to "spar[e] [Rachel] a charge of bigamy ... after finding out that her first husband intends to divorce her under Danish law on the grounds of adultery and desertion." Thereafter, Rachel supported her children in St. Croix, keeping a small store in Christiansted.

She contracted a severe fever and died on February 19, 1768, at 1:02 a.m., leaving Hamilton orphaned.

In probate court, Rachel's "first husband seized her estate" and obtained the few valuables Rachel had owned, including some household silver. Many items were auctioned off, but a friend purchased the family's books and returned them to the young Hamilton.

Hamilton became a clerk at Beekman and Cruger, which traded with the New England colonies; he was left in charge of the firm for five months in 1771 while the owner was at sea.

He and his older brother, James Jr., were adopted briefly by a cousin, Peter Lytton, but when Lytton passed away suddenly, the brothers were separated.

James apprenticed with a local carpenter, while Alexander was adopted by a Nevis merchant, Thomas Stevens.

Hamilton continued clerking, but he remained an avid reader, later developing an interest in writing, and began to desire a life outside the small island where he lived.

He wrote an essay published in the Royal Danish-American Gazette, a detailed account of a hurricane that had hit Christiansted hard on August 30, 1772.

Hamilton's essay would be a turning point in his life. The essay impressed community leaders, who collected a fund to send the young Hamilton to the colonies for his education.

Education

In the autumn of 1772, Hamilton arrived in the middle colony, New Jersey, at Elizabethtown.

In 1773, he studied with Francis Barber at Elizabethtown in preparation for college work. He came under the influence of William Livingston, a leading intellectual and revolutionary with whom he lived for a time at his Liberty Hall.

Hamilton entered King's College in New York City in the autumn of 1773.

In what is credited as his first public appearance, on July 6, 1774, at the Liberty Pole at King's College, Hamilton's friend Robert Troup spoke of Hamilton's ability to clearly and concisely explain the rights and reasons the patriots have in their case against the British.

Hamilton, Troup, and four other undergraduates formed an unnamed literary society that is regarded as a precursor of the Philolexian Society.

When the Church of England clergyman Samuel Seabury published a series of pamphlets promoting the Loyalist cause in 1774, Hamilton responded anonymously with his first political writings, A Full Vindication of the Measures of Congress and The Farmer Refuted.

Seabury essentially tried to provoke fear in the colonies, and his main objective was to stop the potential of a union among the colonies. Hamilton published two additional pieces attacking the Quebec Act and may have also authored the fifteen anonymous installments of "The Monitor" for Holt's New York Journal.

Although Hamilton was a supporter of the American Revolution at this prewar stage, he did not approve of mob reprisals against Loyalists. On May 10, 1775, Hamilton won credit for saving his college president, Myles Cooper, a Loyalist, from an angry mob by speaking to the crowd long enough for Cooper to escape.

American Revolutionary War

In 1775, after the first engagement of American troops with the British at Lexington and Concord, Hamilton and other King's College students joined a New York volunteer militia company called the Corsicans, later renamed or reformed as the Hearts of Oak.

He drilled with the company before classes in the graveyard of nearby St. George's Chapel. Hamilton studied military history and tactics on his own and was soon recommended for promotion.

Under fire from HMS Asia, he led a successful raid for British cannons in the Battery, the capture of which resulted in the Hearts of Oak becoming an artillery company.

Through his connections with influential New York patriots such as Alexander McDougall and John Jay, he raised the New York Provincial Company of Artillery of sixty men in 1776 and was elected captain. It took part in the campaign of 1776 around New York City, particularly at the Battle of White Plains; at the Battle of Trenton, it was stationed at the high point of the town, the meeting of the present Warren and Broad Streets, to keep the Hessians in check.

Hamilton was invited to become an aide to William Alexander, Lord Stirling, and one other general, perhaps Nathanael Greene or Alexander McDougall. He declined these invitations, believing his best chance for improving his station in life was glory on the battlefield.

Hamilton eventually received an invitation he felt he could not refuse: to serve as George Washington's aide, with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel.

Hamilton served for four years as Washington's chief staff aide. He handled letters to Congress, state governors, and the most powerful generals in the Continental Army; he drafted many of Washington's orders and letters at the latter's direction; he eventually issued orders from Washington over Hamilton's own signature.

Hamilton was involved in a wide variety of high-level duties, including intelligence, diplomacy, and negotiation with senior army officers as Washington's emissary.

On July 31, 1781, Washington assigned Hamilton as commander of a New York light infantry battalion. In the planning for the assault on Yorktown, Hamilton was given command of three battalions, which were to fight in conjunction with the allied French troops in taking Redoubts No. 9 and No. 10 of the British fortifications at Yorktown.

Hamilton and his battalions fought bravely and took Redoubt No. 10 with bayonets in a nighttime action, as planned. The French also fought bravely, suffered heavy casualties, and took Redoubt No. 9. These actions forced the British to surrender an entire army at Yorktown, Virginia, effectively ending their major British military operations in North America.

Rise in Politics

Hamilton, along with John Jay and future political opponent James Madison, penned the influential Federalist Papers.

After the ratification of the Constitution, George Washington was elected as the first President of the United States of America, and he appointed Alexander Hamilton as the Secretary of the Treasury.

Hamilton felt that the debt that the United States had accrued during the American Revolutionary War was the price it paid for its liberty.

To Hamilton, the proper handling of the government debt would also allow America to borrow at affordable interest rates and would also be a stimulant to the economy.

Hamilton divided the debt into national and state and further divided the national debt into foreign and domestic debt. While there was agreement on how to handle the foreign debt, there was not with regard to the national debt held by domestic creditors.

During the Revolutionary War, affluent citizens had invested in bonds, and war veterans had been paid with promissory notes and IOUs that plummeted in price during the Confederation. In response, the war veterans sold the securities to speculators for as little as fifteen to twenty cents on the dollar.

Hamilton felt the money from the bonds should not go to the soldiers but to the speculators who had bought the bonds from the soldiers, as they had little faith in the country's future.

The process of attempting to track down the original bond holders along with the government showing discrimination among the classes of holders if the war veterans were to be compensated also weighed in as factors for Hamilton.

As for the state debts, Hamilton suggested consolidating it with the national debt and labeling it as federal debt for the sake of efficiency on a national scale.

The last portion of the report dealt with eliminating the debt by utilizing a sinking fund that would retire five percent of the debt annually until it was paid off.

Due to the bonds being traded well below their face value, the purchases would benefit the government as the securities rose in price. When the report was submitted to the House of Representatives, detractors soon began to speak against it.

Hamilton was a leader in the establishment of the United States Bank. The United States Bank would exist until Andrew Jackson's administration.

Political Relationships

Alexander Hamilton was a strong personality in U.S. politics and made many political enemies along the way, including Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Aaron Burr. He also maintained a positive and influential relationship with George Washington and became the leader of the Federalist Party.

Hamilton's influence led to the election of John Adams as the 2nd President of the United States. He opposed Jefferson's political beliefs and believed him to be a radical.

He and John Adams did not agree on much during the Presidency, and it led to the two of them parting ways. Adams did not trust Hamilton's motives, and although he disagreed with Jefferson's ideals and saw them as extreme, he trusted Jefferson's character.

Hamilton disliked Aaron Burr and believed him to be evil. He fought him at every opportunity and always tried to deny him political office. Their rivalry came to a climax when Aaron Burr challenged Hamilton to a duel.

Although he made many enemies, he also had many powerful friends, including George Washington. He served under Washington in the Revolutionary War and became his Secretary of Treasury during Washington's Presidency. Washington was loyal to Hamilton until his death in 1799.

Alexander Hamilton Facts: The Duel

Alexander Hamilton regarded Aaron Burr as a power-hungry politician who did not care about the Constitution. While he and Jefferson disagreed on policies and had many heated exchanges, he believed Jefferson was loyal to the Constitution and would not use his power to thwart it.

Hamilton campaigned against Burr during every election he participated in. Finally, Hamilton insulted Burr at a dinner party, and Burr learned of it and felt a need to defend his honor. Burr challenged Hamilton to a duel, to which Hamilton accepted.

Hamilton wrote a series of letters defending his decision to take part in the duel.

Both men fired a shot at the duel. Burr's shot struck Hamilton's abdomen and paralyzed him, while Hamilton's shot struck a tree branch above Burr's head.

There are arguments over who fired first. Some suggest Hamilton deliberately missed, while some say his shot was fired after being struck by Burr's bullet. Both witnesses said different men fired first.

Hamilton was mortally wounded and died the next day.

Burr was charged with murder but never saw a trial

Alexander Hamilton Facts: Death and Legacy

Alexander Hamilton died July 12, 1804. He was eulogized by Gouverneur Morris.

He is known for his service in the Revolutionary War, The United States Bank, His work as the first Secretary of the Treasury, being the founder of the Federalist Party, and his face on the 10-dollar bill.

Hamilton is another founding father whose religion and influences is often questioned. Hamilton's conception of human nature shaped his political thought.

His predominantly and radically liberal conception of human nature was based on John Locke's concept of liberty, Thomas Hobbes's concept of power, and Niccolò Machiavelli's concept of the 'effectual truth.'

It thus stressed the necessary relation between self-interest and republican government and entailed the repudiation of classical republican and Christian political ideals.

But Hamilton's love of liberty was nonetheless rooted in a sense of classical nobility and Christian philanthropy that simultaneously elevated and contradicted his liberalism.

The complex relation between liberty, nobility, philanthropy, and power in Hamilton's conception of human nature, in effect, defined his thought and exposed the strengths and weaknesses of his ideology. That complexity formed the spirit of his liberal republicanism.

No figure in the era of American history has had so many ups and downs, so many champions and detractors as Hamilton over the last two centuries. Historians continue to ask, "Was he a closet monarchist or a sincere republican? A victim of partisan politics or one of its most active promoters? A lackey for British interests or a foreign policy mastermind? An economic genius or a shill for special interests? The father of a vigorous national government or the destroyer of genuine federalism? A defender of governmental authority or a dangerous militarist?"

It is believed that Alexander Hamilton became a Christian a decade before his death.

He is buried alongside his wife in the Trinity Church Cemetery.