The Federalist Party was an American political party during the First Party System, in the period 1791 to 1816, with remnants lasting into the 1820s.

The Federalists controlled the federal government until 1801. The party was formed by Alexander Hamilton, who, in about 1791-92, built a network of supporters in the principal cities to support his fiscal policies.

Jump to:

The Federalists were nationalists who wanted a fiscally and militarily strong nation-state and showed little interest in states' rights.

It rejected the French Revolution and preferred Britain in the wars that Britain and France fought from 1793 to 1815. The party fought for Hamilton's financial programs, including assuming the state debts left over from the revolution, creating a tax system to pay those debts, and creating a national bank to support faster economic growth.

The new party advocated a loose construction of the Constitution based on the "Elastic Clause." It believed in rule by a well-educated elite and thus appealed to merchants, bankers, lawyers, editors, landowners, and industrialists.

Its most powerful leader was Alexander Hamilton; George Washington never joined the party, but he supported most of its programs and became its hero. The Party built a network of newspapers and had substantial support from religious leaders, especially in New England.

Unlike the opposition Jeffersonians, it paid little attention to grassroots organizing. In the long run, one of the party's most influential members was John Marshall, who strengthened the powers of the judiciary while Chief Justice of the United States.

The elections of 1792 were the first ones to be contested on anything resembling a partisan basis. While it was not partisan on a national level with the election of George Washington, parties began to emerge in local elections.

In New York, the race for governor was organized along these lines. The candidates were John Jay, a Hamiltonian, and incumbent George Clinton, who was allied with Jefferson.

Rise of the Federalist Party

In 1789, Alexander Hamilton became U.S. Secretary of the Treasury with the largest and most active department of government, and (usually) with Washington's support. Hamilton wanted a strong national government and decided that required financial credibility and a national network of supporters.

Hamilton proposed an ambitious economic program that involved the assumption of the debts that the states had run up in fighting the Revolutionary War by creating a national debt and the means (taxes) to pay it off. In addition, he set up a national bank. Hamilton organized alliances and succeeded in getting Congress to pass these measures.

James Madison, Hamilton's ally in the fight to ratify the United States Constitution, dropped his nationalism in response to demands in his Virginia district and joined with Jefferson in opposing Hamilton's program.

By 1790, Hamilton started building a nationwide coalition. Realizing the need for vocal political support in the states, he formed connections with like-minded nationalists and local factions and used his network of Treasury agents to link together friends of the government, especially merchants and bankers, in the new nation's dozen small cities.

His attempts to manage politics in the national capital to get his plans through Congress then "brought strong responses across the country. In the process, what began as a capital faction soon assumed status as a national faction and then, finally, as the new Federalist party."

By 1792 or 1793, newspapers started calling Hamilton supporters "Federalists" and the opponents "Republicans." Religious and educational leaders hostile to the French Revolution joined the Federalist coalition, especially in New England.

The state networks of both parties began to operate in 1794 or 1795. Patronage now become a factor. The winner-take-all election system opened a wide gap between winners, who got all the patronage, and losers, who got none.

Hamilton had over 2000 Treasury jobs to dispense, while Jefferson had one part-time job in the State Department, which he gave to journalist Philip Freneau. In New York, however, George Clinton won the election for Governor and used the vast state patronage fund to help the Republican cause.

Washington tried and failed to moderate the feud between his two top cabinet members. He was re-elected without opposition in 1792.

The Democratic-Republicans nominated New York's Governor Clinton to replace Federalist John Adams as vice president, but Adams won. The balance of power in Congress was close, with some members still undecided between the parties.

In early 1793, Thomas Jefferson secretly prepared resolutions for William Branch Giles, Congressman from Virginia, to introduce that would have repudiated the Treasury Secretary and destroyed the Washington Administration.

Hamilton effectively defended his administration of the nation's complicated financial affairs, which none of his critics could decipher until the arrival in Congress of Albert Gallatin in 1793.

Federalist Influence on Foreign Affairs

The French Revolution and the subsequent war between royalist Britain and republican France--decisively shaped American politics, 1793-1800, and indeed threatened to entangle the nation in wars that "mortally threatened its very existence."

The French revolutionaries guillotined King Louis XVI in January 1793, leading the British to declare war to restore the monarchy. The King had been decisive in helping America achieve independence; now, he was dead, and many of the pro-American aristocrats in France were exiled or executed.

Federalists warned that American republicans threatened to replicate the horrors of the French Revolution and successfully mobilized most conservatives and many clergymen.

The Republicans, some of whom had been strong Francophiles, responded with support, even through the Reign of Terror, when thousands were guillotined.

Many of those executed had been friends of the United States, such as the Comte D'Estaing, whose fleet defeated the British at Yorktown.

The Republicans denounced Hamilton, Adams, and even Washington as friends of Britain, as secret monarchists, and as enemies of the republican values that all true Americans cherished. The level of rhetoric reached a fever pitch.

France, in 1793, sent a new minister, Edmond-Charles Genêt (known as Citizen Genêt), who systematically mobilized pro-French sentiment and encouraged Americans to support France's war against Britain and Spain.

Genet funded local Democratic-Republican Societies that attacked Federalists; he hoped for a favorable new treaty and for repayment of the debts owed to France.

Acting aggressively, Genêt outfitted privateers that would sail with American crews under a French flag and attack British shipping. He tried to organize expeditions of Americans who would invade Spanish Louisiana and Spanish Florida.

When Secretary of State Jefferson told Genêt he was pushing American friendship past the limit, Genêt threatened to go over Washington's head and rouse public opinion on behalf of France. Even Jefferson agreed this was blatant foreign interference in domestic politics.

The Federalists emphasized that elected representatives expressed the will of the people, not mass rallies. Genêt's extremism seriously embarrassed the Jeffersonians and cooled popular support for promoting the French Revolution or getting involved in its wars.

Recalled to Paris for execution, Genêt kept his head and instead went to New York, where later he became a citizen and married the daughter of Governor Clinton. Jefferson left office, ending the coalition cabinet and allowing the Federalists to dominate.

The Jay Treaty in 1794-95 was the effort by George Washington and Hamilton to resolve numerous difficulties with Britain. Some of these issues dated to the Revolution, (such as boundaries, debts owed in each direction, and the continued presence of British forts in the Northwest Territory.

In addition, America hoped to open markets in the British Caribbean and disputes stemming from the naval war between Britain and France. Most of all, the goal was to avert a war with Britain, a war opposed by the Federalists that some historians claim the Jeffersonians wanted.

As a neutral, the United States argued it had the right to carry goods anywhere it wanted. The British nevertheless seized American ships carrying goods from the French West Indies. The Federalists favored Britain in the war, and by far, most of America's foreign trade was with Britain; hence, a new treaty was called for.

The British agreed to evacuate the western forts, open their West Indies ports to American ships, allow small vessels to trade with the French West Indies, and set up a commission that would adjudicate American claims against Britain for seized ships and British claims against Americans for debts incurred before 1775.

One possible alternative was war with Britain, a war that America was ill-prepared to fight.

The Republicans wanted to pressure Britain to the brink of war. Therefore, they denounced the Jay Treaty as an insult to American prestige, a repudiation of the French alliance of 1777, and a severe shock to Southern planters who owed those old debts and who were never to collect for the lost slaves the British captured.

Republicans protested against the treaty, but the Federalists controlled the United States Senate, and they ratified it by exactly the necessary ⅔ vote, 20-10, in 1795.

The pendulum of public opinion swung toward the Republicans after the Treaty fight, and in the South, the Federalists lost most of the support they had among planters.

The Whiskey Rebellion

The excise tax of 1791 caused grumbling from the frontier, including threats of tax resistance. Corn, the chief crop on the frontier, was too bulky to ship over the mountains to market unless it was first distilled into whiskey. This was profitable, as the United States population consumed, per capita, relatively large quantities of liquor.

After the excise tax, the backwoodsmen complained the tax fell on them rather than on the consumers. Cash-poor, they were outraged that they had been singled out to pay off the "financiers and speculators" back East and to salary the federal revenue officers who began to swarm the hills looking for illegal stills.

Insurgents shut the courts and hounded federal officials, but Jeffersonian leader Albert Gallatin mobilized the western moderates and thus forestalled a serious outbreak.

Washington, seeing the need to assert federal supremacy, called out 15,000 state militia and marched toward Pittsburgh to suppress this Whiskey Rebellion.

The rebellion evaporated in late 1795 as Washington approached, personally leading the army (the first and only example of a President ever doing so). The rebels dispersed, and there was no fighting.

Federalists were relieved that the new government proved capable of overcoming rebellion, while Republicans, with Gallatin their new hero, argued there never was a real rebellion, and the whole episode was manipulated in order to accustom Americans to a standing army.

Angry petitions flowed in from three dozen Democratic-Republican Societies created by Citizen Genêt. Washington attacked the societies as illegitimate; many disbanded. Federalists now ridiculed Republicans as "democrats" or "Jacobins".

Washington refused to run for a third term, establishing a two-term precedent that was to stand until 1940 and eventually to be enshrined in the Constitution as the 22nd Amendment.

Washington warned in his Farewell Address against involvement in European wars and lamented the rising North-South sectionalism and party spirit in politics that threatened national unity.

War of the Press

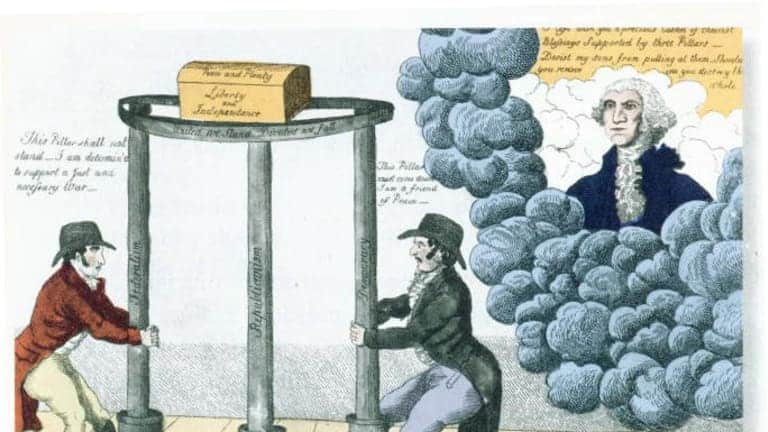

To strengthen their coalitions and hammer away constantly at the opposition, both parties sponsored newspapers in Philadelphia and other major cities.

On the Republican side, Philip Freneau and Benjamin Franklin Bache blasted the administration with all the scurrility at their command.

Bache, in particular, targeted Washington himself as the front man for monarchy who must be exposed. To Bache, George Washington was a cowardly general and a money-hungry baron who saw the American Revolution as a means to advance his fortune and fame. President John Adams was a failed diplomat who never forgave the French their love of Benjamin Franklin and who cherished the crown for himself and his descendants, and Alexander Hamilton was the most inveterate monarchist of them all.

The Federalists, with twice as many newspapers at their command, slashed back with equal vituperation; John Fenno and "Peter Porcupine" were their nastiest penmen, and Noah Webster their most learned; Hamilton subsidized the Federalist editors, wrote for their papers and in 1801 established his own paper, the New York Evening Post.

Election of 1796

Hamilton distrusted John Adams but was unable to block his claims to the succession. The election of 1796 was the first partisan affair in the nation's history and one of the more scurrilous in terms of newspaper attacks.

Adams swept New England and Jefferson the South, with the middle states leaning to Adams. Thus, Adams was the winner by a margin of three electoral votes, and Jefferson, as the runner-up, became Vice President under the system set out in the Constitution prior to the ratification of the 12th Amendment.

Foreign affairs continued to be the central concern of American politics, for the war raging in Europe threatened to drag on the United States.

The new President was a loner who made decisions without consulting Hamilton or other High Federalists. Benjamin Franklin once quipped that Adams was a man always honest, often brilliant, and sometimes mad.

Adams was popular among the Federalist rank and file but had neglected to build state or local political bases of his own and neglected to take control of his own cabinet. As a result, his cabinet answered more to Hamilton than to himself.

Alien and Sedition Acts

After an American delegation was insulted in Paris in the XYZ affair, public opinion ran strongly against the French. An undeclared "Quasi-War" with France from 1798 to 1800 saw each side attacking and capturing the other's shipping. It was called "quasi" because there was no declaration of war, but escalation was a serious threat.

There, The Federalists, at the peak of their popularity, took advantage by preparing for an invasion by the French Army. To silence Administration critics, the Federalists passed the Sedition Act. Several opposition editors were convicted and fined or sent to jail.

The Alien Act empowered the President to deport such aliens as he deemed to be dangerous. Jefferson and Madison secretly wrote the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions passed by the two states' legislatures that declared the Alien and Sedition Acts unconstitutional and insisted the states had the power to nullify federal laws.

Undaunted, the Federalists created a navy with new frigates and a large new army, with Washington in nominal command and Hamilton in actual command. To pay for it all, they raised taxes on land, houses, and slaves, leading to serious unrest.

In one part of Pennsylvania, the Fries' Rebellion broke out, with people refusing to pay the new taxes. John Fries was sentenced to death for treason but received a pardon from Adams. In the elections of 1798, the Federalists did very well, but the tax issue started hurting the Federalists in 1799.

Early in 1799, Adams decided to free himself from Hamilton's overbearing influence, stunning the country and throwing his party into disarray by announcing a new peace mission to France.

The mission eventually succeeded, the "Quasi-War" ended, and the new army was largely disbanded. Hamiltonians called Adams a failure, and in turn, Adams fired Hamilton's supporters still in the cabinet.

Hamilton and Adams intensely disliked one another, and the Federalists split between supporters of Hamilton and supporters of Adams.

Hamilton became embittered over his loss of political influence and wrote a scathing criticism of Adam's performance as President of the United States in an effort to throw Federalist support to Charles Pinckney; inadvertently, this split the Federalists and helped give the victory to Thomas Jefferson.

Election of 1800

Adams' peace moves proved popular with the Federalist rank and file, and he seemed to stand a good chance of reelection in 1800.

Jefferson was again the opponent, and Federalists pulled out all stops in warning that he was a dangerous revolutionary, hostile to religion, who would weaken the government, damage the economy, and get into war with Britain.

The Republicans crusaded against the Alien and Sedition laws and the new taxes and proved highly effective in mobilizing popular discontent.

The election hinged on New York: its electoral votes were cast by the legislature, and given the balance of north and south, they would decide the presidential election.

Aaron Burr brilliantly organized his forces in New York City in the spring elections for the state legislature. By a few hundred votes, he carried the city and, thus, the state legislature and guaranteed the election of a Republican President.

As a reward, he was selected by the Republican caucus in Congress as their vice presidential candidate. Hamilton, knowing the election was lost anyway, went public with a sharp attack on Adams that further divided and weakened the Federalists.

Due to the Republicans' failure to plan by instructing at least one of their electors to vote for Jefferson but not Burr in the electoral college, Burr and Jefferson received the same vote, 73 each, so it was up to the House of Representatives to break the tie.

There the Federalists were strong enough to deadlock the election, with some talk of their throwing their support to elect Burr.

Hamilton considered Burr to be a scoundrel and threw his weight into the contest, allowing Jefferson to take office. "We are all republicans. We are all federalists," proclaimed Jefferson in his inaugural address.

His patronage policy was to let the Federalists disappear through attrition. Those Federalists, such as John Quincy Adams and Rufus King, willing to work with him were rewarded with senior diplomatic posts, but there was no punishment for the opposition.

Jefferson had a very successful first term, typified by the Louisiana Purchase. The thoroughly disorganized Federalists hardly offered an opposition to his reelection.

In New England and in some districts in the middle states, the Federalists clung to power, but the tendency from 1800 to 1812 was steady slippage almost everywhere as the Republicans perfected their organization and the Federalists tried to play catch-up.

Some younger leaders tried to emulate the republican tactics, but their overall disdain of democracy, along with the upper-class bias of the party leadership, eroded public support.

In the South, the Federalists steadily lost ground everywhere.

Federalists in the Minority

The Federalists continued for several years to be a major political party in New England and the Northeast but never regained control of the Presidency or the Congress.

With the death of Washington and Hamilton and the retirement of Adams, the Federalists were left without a strong leader and grew steadily weaker. A few younger leaders did appear, notably Daniel Webster.

Federalist policies favored factories, banking, and trade over agriculture and thus became unpopular in the growing Western states.

They were increasingly seen as aristocratic and unsympathetic to democracy. In the South, the party had lingering support in Maryland but elsewhere was crippled by 1800 and faded away by 1808.

Thanks to the passing of the Judiciary Act of 1789 during Washington's term, the Federalists did maintain power within the Supreme Court.

Massachusetts and Connecticut were the party strongholds. One historian explains how well-organized the party was in Connecticut:

It was only necessary to perfect the working methods of the organized body of office-holders who made up the nucleus of the party. There were the state officers, the assistants, and a large majority of the Assembly. In every county, there was a sheriff with his deputies. All of the state, county, and town judges were potential and generally active workers. Every town had several justices of the peace, school directors, and, in Federalist towns, all the town officers who were ready to carry on the party's work. Every parish had a "standing agent," whose anathemas were said to convince at least ten voting deacons. Militia officers, state attorneys, lawyers, professors, and schoolteachers were in the van of this "conscript army." In all, about a thousand or eleven hundred dependent officer-holders were described as the inner ring, which could always be depended upon for their own and enough more votes within their control to decide an election. This was the Federalist machine.

After 1800, the major Federalist role came in the judiciary. Although Jefferson managed to repeal the Judiciary Act of 1801 and thus dismiss many Federalist judges, their effort to impeach Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase in 1804 failed.

Led by the last great Federalist, John Marshall, as Chief Justice from 1801 to 1835, the Supreme Court carved out a unique and powerful role as the protector of the Constitution and promoter of nationalism.

President Jefferson imposed an embargo on Britain in 1807; the Embargo Act of 1807 prevented all American ships from sailing to a foreign port. The idea was that the British were so dependent on American supplies that they would come to terms.

For 15 months, the Embargo wrecked American export businesses, largely based in the Boston-New York region, causing a sharp depression in the Northeast.

Evasion was common, and Jefferson and Treasury Secretary Gallatin responded with tightened police controls more severe than anything the Federalists had ever proposed.

Public opinion was highly negative, and a surge of support breathed fresh life into the Federalist Party. The Republicans nominated Madison for the presidency in 1808.

Federalists, meeting in the first-ever national convention, considered the option of nominating Vice President George Clinton as their own candidate but balked at working with him and again chose Charles Pinckney, their 1804 candidate.

Madison lost New England but swept the rest of the country and carried a Democratic-Republican Congress. Madison dropped the Embargo, opened up trade again, and offered a carrot-and-stick approach.

If either France or Britain agreed to stop their violations of American neutrality, the U.S. would cut off trade with the other countries. Tricked by Napoleon into believing France had acceded to his demands, Madison turned his wrath on Britain.

Thus, the nation was at war during the 1812 presidential election, and war was the burning issue. In their second national convention, the Federalists, now the peace party, nominated DeWitt Clinton, the dissident Democratic-Republican mayor of New York City and an articulate opponent of the war.

Madison ran for reelection, promising a relentless war against Britain and an honorable peace. Clinton, denouncing Madison's weak leadership and incompetent preparations for war, could count on New England and New York.

To win, he needed the middle states, and there, the campaign was fought out. Those states were competitive and had the best-developed local parties and the most elaborate campaign techniques, including nominating conventions and formal party platforms.

The Tammany Society in New York City went all out for Madison; the Federalists finally adopted the club idea in 1809.

Their Washington Benevolent Societies were semi-secret membership organizations that played a critical role in every northern state in holding meetings and rallies and mobilizing Federalist votes.

New Jersey went for Clinton, but Madison carried Pennsylvania and thus was reelected with 59% of the Electoral votes.

Opposition to the War of 1812

The War of 1812 went poorly for the Americans for two years. Even though Britain was concentrating its military efforts on its war with Napoleon, the United States still failed to make any headway on land and was effectively blockaded at sea by the Royal Navy.

The British raided and burned Washington D.C. in 1814 and sent a large veteran army to capture New Orleans.

The war was especially unpopular in New England: the declaration of war had been driven by Westerners and Southerners looking to grab more land from the Spanish in Florida and the British in Canada and to deny support to hostile British-armed Native American tribes led by Tecumseh in the Northwest and Southwest Territories.

Moreover, the New England economy was highly dependent on trade, and the British blockade threatened to destroy it entirely.

In 1814, the British finally managed to enforce their blockade on the New England coast, so the Federalists of New England sent delegates to the Hartford Convention in December 1814.

During the proceedings of the Hartford Convention, secession from the Union was discussed, though the resulting report listed a set of grievances against the Democratic-Republican federal government and proposed a set of Constitutional amendments to address these grievances.

It also indicated that if these proposals were ignored, then another convention should be called and given "such powers and instructions as the exigency of a crisis may require."

The Federalist Massachusetts Governor had already secretly sent word to England to broker a separate peace accord. Three Massachusetts "ambassadors" were sent to Washington to negotiate on the basis of this report.

By the time the Federalist "ambassadors" got to Washington, the war was over, and news of Andrew Jackson's stunning victory in the Battle of New Orleans had raised American morale immensely.

The "ambassadors" slunk back to Massachusetts, but not before they had done fatal damage to the Federalist Party. The Federalists were thereafter associated with the disloyalty and parochialism of the Hartford Convention and destroyed as a political force.

They fielded their last presidential candidate in 1816. With its passing partisan hatreds and newspaper feuds on the decline, the nation entered an "Era of Good Feelings."

The last traces of Federalist activity came in Delaware localities in the 1820s.

Conclusion

The Federalists were dominated by conservative businessmen and merchants in the major cities who supported a strong national government. The party was closely linked to the modernizing, urbanizing financial policies of Alexander Hamilton.

These policies included the funding of the national debt and also the state debts incurred during the Revolutionary War, the incorporation of a national Bank of the United States, the support of manufactures and industrial development, and the use of a tariff to fund the Treasury.

In foreign affairs, the Federalists opposed the French Revolution, engaged in the "Quasi War" with France in 1798-99, sought good relations with Britain, and sought a strong army and navy.

Ideologically, the controversy between Republicans and Federalists stemmed from a difference of principle and style. In terms of style, the Federalists distrusted the public, thought the elite should be in charge, and favored national power over state power.

Republicans distrusted Britain, bankers, and merchants and did not want a powerful national government. In the end, the nation synthesized the two positions, adopting representative democracy and a strong nation-state.

Just as important, American politics by the 1820s accepted the two-party system whereby rival parties stake their claims before the electorate, and the winner takes control of the government.

As time went on, the Federalists lost appeal with the average voter and were generally not equal to the tasks of party organization; hence, they grew steadily weaker as the political triumphs of the republican party grew.

For economic and philosophical reasons, the Federalists tended to be pro-British – the United States engaged in more trade with Great Britain than with any other country – and vociferously opposed Jefferson's ill-advised Embargo Act of 1807 and the seemingly deliberate provocation of war with Britain by the Madison Administration.

During "Mr. Madison's War," as they called it, the Federalists attempted a comeback, but the patriotic euphoria that followed the war undercut their pessimistic appeals.

After 1816, the Federalists had no national influence apart from John Marshall's Supreme Court. They had some local support in New England, New York, eastern Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Delaware.

After the collapse of the Democratic-Republican Party in the course of the 1824 presidential election, most surviving Federalists joined former Democratic-Republicans like Henry Clay to form the National Republican Party, which was soon combined with other anti-Jackson groups to form the Whig Party.

Some former Federalists like James Buchanan and Roger B. Taney became Jacksonian Democrats.

The name "Federalist" came increasingly to be used in political rhetoric as a term of abuse and was denied by the Whigs, who pointed out that their leader, Henry Clay, was the Democratic-Republican party leader in Congress during the 1810s.

The "Old Republicans," led by John Randolph of Roanoke, refused to form a coalition with the Federalists and instead set up a separate opposition that Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, John C. Calhoun, and Henry Clay had, in effect adopted Federalist principles by purchasing the Louisiana Territory, chartering the Second national bank, promoting internal improvements, raised tariffs to protect factories, and promoting a strong army and navy after the failures of the War of 1812.