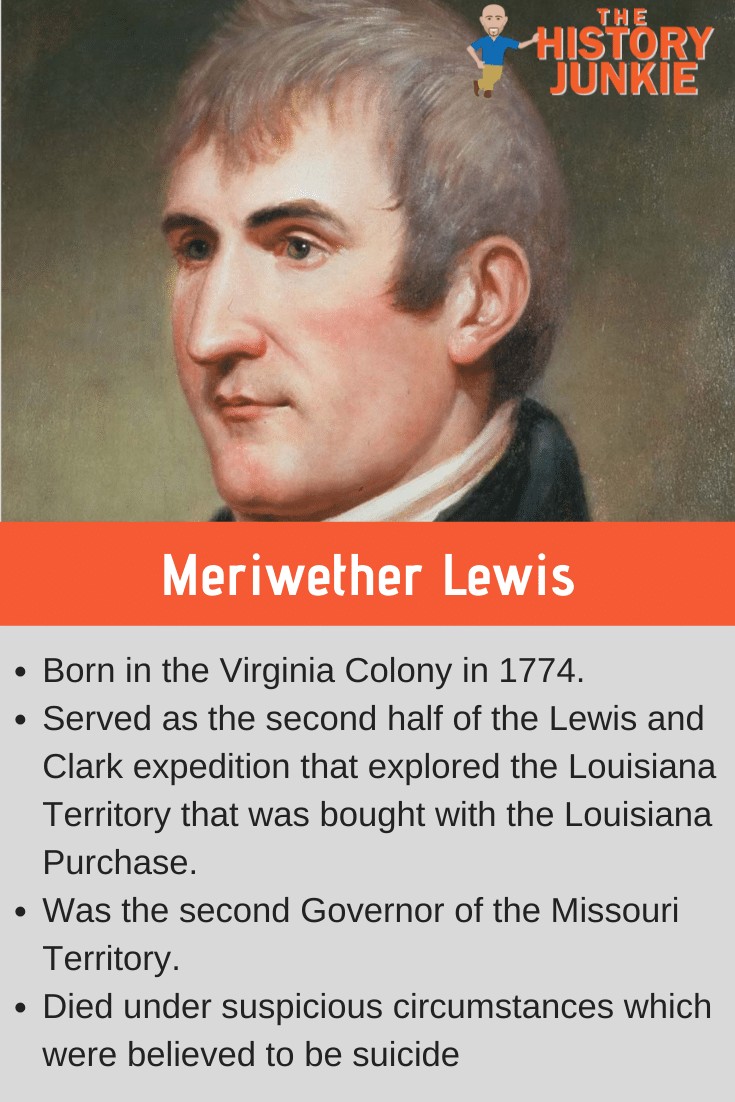

Meriwether Lewis was a famous explorer who became famous as the co-leader of the Lewis and Clark expedition of 1804-06, which explored the territory of the Louisiana Purchase after the United States acquired it from France in 1803, as well as the Pacific Northwest.

It is generally reckoned as one of the most successful and significant expeditions of its kind in modern history, and Lewis has been almost universally praised for his leadership of the operation.

After the expedition's return, he served as governor of the territory of Upper Louisiana before dying under mysterious circumstances in 1809.

Early Life

Meriwether Lewis was born on August 18, 1774, at Locust Hill Plantation in Albemarle County, Virginia Colony, just west of modern-day Charlottesville.

Of Welsh descent, his parents were William and Lucy Lewis, cousins and respected members of the Virginia landowning gentry.

William Lewis joined the Continental Army following the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War and served as an officer until his death in November 1779 from pneumonia; the following year, Meriwether's mother, Lucy, remarried Captain John Marks, also of Virginia.

Around 1783, the family moved south to the Goosepond Community along the Broad River in what is now Oglethorpe County, Georgia.

As a child raised along the frontier, young Meriwether Lewis developed a love of hunting and exploring and was said in later family accounts to have tremendous intelligence and presence of mind.

According to one popular story, at the age of only eight or nine, he calmly shot dead a bull charging toward him and learned a great deal from his mother about the use of herbs and other wild plants for medicinal purposes.

With his upbringing in the wilderness, he was not able to obtain a formal education during his childhood, and at the age of thirteen returned to Virginia, where he studied under a series of private teachers, mostly clergymen, until 1792.

At that time, following his stepfather's death, he arranged the return of his mother and the rest of the family to Virginia and established himself at Locust Hill Plantation as his father's heir.

Army Career

In response to the outbreak of the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794, Lewis enlisted in a Virginia militia unit raised to defeat the uprising.

He joined, in his own words, "to support the glorious cause of Liberty, and my Country," seeing the rebellion as a threat to break up the new nation; he may also have become bored with the life of a Virginia planter and been eager for adventure.

That autumn, he was given a commission as an ensign in the militia, spending the winter on patrol in western Pennsylvania after the defeat of the rebellion, and in May 1795, entered the regular army at the same rank.

Lewis spent most of the next six years at a variety of army posts on the frontier, mostly in the Northwest Territory. He served under General Anthony Wayne during the conclusion of some of the campaigns against the Native American tribes in the Ohio Valley and frequently traveled back and forth between Detroit, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and other frontier communities.

During this time, Lewis gained a great deal of practical knowledge concerning journeying in the wilderness, navigating, using boats and other watercraft, and record-keeping.

He also learned a lot about Native Americans and their languages and the usefulness of relying on them as guides. Equally important, he would spend several months in an elite rifle company commanded by his fellow Virginian, William Clark, and the two came to know each other intimately.

Thanks in part to his personal connections as a member of the Virginia planter class but also because of his skill and integrity as an officer, Lewis was steadily promoted through the Army officer corps.

In March 1799, he received the rank of lieutenant and shortly thereafter became regimental paymaster; in December 1800, he was promoted again to captain.

It has been noted that given Lewis' pronounced sympathy for the Democratic-Republican party, his advancement at a time when President John Adams was trying to pack the army with Federalist officers was itself a testament to his abilities.

Presidential Secretary

Upon becoming President in 1801, Thomas Jefferson recruited Lewis, whom he knew as a fellow native of the Albemarle region and as a friend to the family, to be his private secretary.

Jefferson's immediate goal was to have a reliably Republican assistant by his side in implementing certain policies, especially purging the army of Adams' recent Federalist appointees.

As an officer of long service with thorough knowledge of the situation in the army, Lewis was able to compose a roster identifying the most anti-Jeffersonian elements in the army and recommending their removal.

Apart from his work in reducing Federalist influence in the army, Lewis spent most of the next two years engaged in the typical duties of a secretary to the President, drafting and copying official documents and correspondence, advising Jefferson on matters in which he was knowledgeable, and delivering the President's State of the Union speeches to Congress.

Origins of the Expedition

For much of his political career, one of Jefferson's long-term goals had been ensuring gradual westward expansion by the United States, in part by setting out an expedition that could gather scientific information about the territory west of the Mississippi River and establish an American claim to it.

When Jefferson had proposed such an expedition in 1792, Lewis had been among the first volunteers, although his youth and inexperience disqualified him at the time.

By 1802, British explorations in the Pacific Northwest and news that the Spanish territory of Louisiana was to be ceded to France made the President determined to launch such a mission at once.

By this time, given his greater experience on the frontier and the two of them having worked closely together, Lewis made a perfect candidate in Jefferson's eyes.

At some point in the summer or autumn of that year, Jefferson made a final decision to launch the expedition under Lewis' command, and the President soon set out a course of study that would equip him with the scientific skills needed for his journey, such as geography, botany, and astronomy.

The Expedition

Lewis selected William Clark, a fellow Virginian with whom he had served on the frontier in 1795, to serve as a co-leader. They set out by keelboat in 1803 to Wood River, Illinois, at the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi rivers.

The next spring, they began their journey up the Missouri River and, by October, had reached the Mandan villages in present-day North Dakota, where they decided to stay for the winter.

Relying completely upon the goodwill of Indian peoples for their success, Lewis and Clark received food, military protection, and valuable information about the path ahead.

Their most valuable help came in the form of Touissant Charbonneau, a French Canadian whom they hired as an interpreter, and his Shoshone wife Sacagawea, who provided help as a guide and interpreter. Sacagawea's presence helped ensure good relations with the Indian people.

In April 1805, all thirty-three members of the expedition left the Mandan village and started up the Missouri again.

A band of Shoshone led by Sacagawea's brother provided invaluable assistance, primarily horses, as the expedition began to ascend the Rocky Mountains.

After crossing the Bitterroot Mountains, they arrived cold, wet, hungry, and exhausted in the Nez Percé village, were they were taken in.

In November, they traveled down the Columbia River basin and reached the Pacific Ocean in November. They stayed the winter on the Pacific Coast and returned to the United States in 1806.

Death

On September 3, 1809, Lewis set out for Washington, D.C. He hoped to resolve issues regarding the denied payment of drafts he had drawn against the War Department while serving as governor of the Upper Louisiana Territory, leaving him in potentially ruinous debt.

Lewis carried his journals with him for delivery to his publisher. He intended to travel to Washington by ship from New Orleans but changed his plans while floating down the Mississippi River from St. Louis.

He disembarked and decided instead to make an overland journey via the Natchez Trace and then east to Washington.

Robbers preyed on travelers on that road and sometimes killed their victims. Lewis had written his will before his journey and also attempted to hurt himself on this journey but was restrained.

According to a lost letter from October 19, 1809, to Thomas Jefferson, Lewis stopped at an inn on the Natchez Trace called Grinder's Stand, about 70 miles southwest of Nashville, on October 10. After dinner, he retired to his one-room cabin. In the predawn hours of October 11, the innkeeper's wife heard gunshots.

Servants found Lewis badly injured from multiple gunshot wounds, one each to the head and gut. He bled out on his buffalo hide robe and died shortly after sunrise.

The Nashville Democratic Clarion published the account, which newspapers across the country repeated and embellished. The Nashville newspaper also reported that Lewis's throat was cut.

Money that Lewis had borrowed from Major Gilbert Russell at Fort Pickering to complete the journey was missing.

While Lewis's friend Thomas Jefferson and some modern historians have generally accepted Lewis's death as a mental illness, debate continues, as discussed below.

No one reported seeing Lewis shoot himself. Three inconsistent, somewhat contemporary accounts are attributed to Mrs. Grinder, who left no written account or testimony.

Some believe her testimony was fabricated, while others point to it as proof of mental illness. Mrs. Grinder claimed Lewis acted strangely the night before his death: standing and pacing during dinner and talking to himself in the way one would speak to a lawyer, with his face flushed as if it had come on him in a fit.

She continued to hear him talking to himself after he retired, and then, at some point in the night, she heard multiple gunshots, a scuffle, and someone calling for help.

She claimed to be able to see Lewis through the slit in the door crawling back to his room.

However, she never explained why she never investigated further at the time, but only the next morning sent her children to look for Lewis's servants.

Another account claimed the servants found Lewis in the cabin, wounded and bloody, with part of his skull gone, but he lived for several hours. In the last account attributed to Mrs. Grinder, three men followed Lewis up the Natchez Trace, and he pulled his pistols and challenged them to a duel.

In that account, Mrs. Grinder said that she heard voices and gunfire in Lewis's cabin at about 1:00 a.m. She found the cabin empty and a large amount of gunpowder on the floor. Thus, in this account, Lewis's body was found outside the cabin.

Lewis's mother and relatives always contended it was murder. A coroner's jury held an inquest immediately after Lewis's death as provided by local law; however, they did not charge anyone with murdering Lewis.

The jury foreman kept a pocket diary of the proceedings, which disappeared in the early 1900s.

When William Clark and Thomas Jefferson were informed of Lewis's death, they were saddened. He had contributed much to the expansion of the United States.